Books

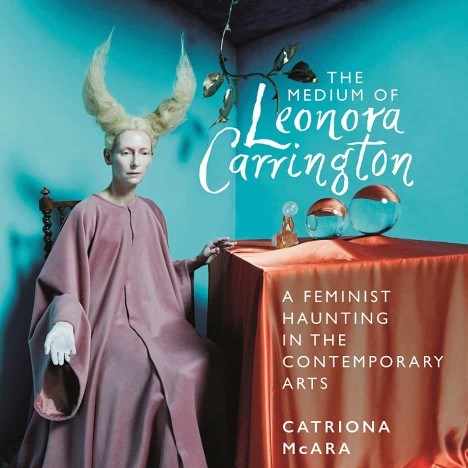

Why Surrealism Matters • The medium of Leonora Carrington

Anna Dezeuze argues that Surrealism’s unfettered individual creativity is increasingly vital in an age when alternative worlds are disappearing and imagination is outsourced to machines

The medium of Leonora Carrington book cover

My art students’ increasingly vocalised ‘who-cares?’ response to my teaching of canonical art history has me regularly asking myself, like colleagues everywhere today, why we should, indeed, care about these long-dead artists. Why, for example, are museums and galleries around the world currently celebrating the centenary of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto? As the ‘Surrealism’ exhibition at the Centre Pompidou boasts an ‘exceptional’ display of Breton’s original, ‘unique’, essay manuscript, the hagiography of another acclaimed white middle-class man certainly rings as out of date. However important Breton himself may have been as an organiser and publicist of Surrealism, his positions have not only come under extensive scrutiny for their misogynist, homophobic, racist and colonialist underpinnings. A significant host of alternative narratives of Surrealism have also sought to dethrone Breton, including a range of in-depth studies of the ways women surrealists diverted and subverted the movement’s original heteronormative vocabulary of desire, and groundbreaking surveys such as ‘Surrealism Beyond Borders’ (at Tate in 2022) that have revealed how artists across the world adapted and re-framed this Euro-centric language for their own purposes.

Translator and Breton-biographer Mark Polizzotti’s recent plea for Why Surrealism Matters certainly takes these critical developments into account and purports to discuss a greater variety of ‘surrealisms’, though Breton remains a central figure in his book. Where he settles for simply highlighting the ambivalence of the movement’s attitude regarding women (ie despite its sexist prejudices, Surrealism did include more female artists than any other movement at the time), in Chapter Three Polizzotti dwells more fully on Surrealism’s politics of cultural appropriation. Notable discussions of how surrealist ideas constituted an impetus for the Haitian uprising in 1945 and the Négritude movement, developed in the 1930s by Martinique poet Aimé Césaire and Senegalese poet and future president Leopold Senghor, shore up the author’s main argument: that the power of Surrealism lies above all in the ‘spirit’ of revolt that it promoted, which responded to different contexts and took different artistic forms. What characterises this spirit, according to Polizzotti, is Surrealism’s collective promotion and exploration of individual liberation against all repressive socio-political orders as much as against ‘partisanship and sectarianism’ (the episode of Breton’s attempt to ally Surrealism to the French Communist Party is effectively detailed). For Polizzotti, then, it is this vital energy and, above all, the artists’ values of ‘decency’ and ‘commitment to a shared set of ideals’ that are still relevant today.

In Polizzotti’s eyes, surrealist works often functioned as little more than means to a political end; consequently, his book shows little concern for either the aesthetics or the artistic legacies of Surrealism. Nevertheless, two important elements, mentioned in passing, are worth picking up here. First, Surrealism’s ‘belief in the inexhaustible capacity for wonder that resides in each of us, here and now’ contributed to its interest in the everyday and in a great variety of both popular and artistic forms from the past as well as the present: in this, the movement ‘differs from standard avant-gardes in its refusal of originality and newness for their own sake’. This may explain why surrealist painting can been coopted by a painter such as Robert Zeller, who has recently coined the notion of a ‘New Surrealism’ (in a 2023 coffee-table book published by Phaidon) to designate a ragbag of contemporary figurative and narrative paintings of greatly uneven quality (including his own). Whether they engage with historical painting, photography or popular culture, such works produce a variety of ambiguous effects that the author subsumes under the nebulous term ‘uncanny’. In spite of his survey of the historical movement, Zeller’s analysis of this ‘New Surrealism’ fails to move beyond a set of surrealist clichés, which relates to a second point mentioned by Polizzotti: that the ‘surreal’ has become an inescapable ‘catchall term’ in contemporary popular discourse, and that ‘Surrealist-inflected imagery has gotten so prevalent that it doesn’t just fade into the landscape as become the landscape’.

Polizzotti points in passing to a loose contemporary grouping that seems more compelling than the ‘New Surrealism’ when he mentions D Scot Miller’s 2009 ‘Afro-Surreal Manifesto’, which cites Césaire and Senghor along with Cuban surrealist Wilfredo Lam as its cast of historical references. In contradistinction to Afro-futurism, Afro-Surrealism is, above all, according to Miller, ‘about the present’, while at times appropriating past symbols of European slavery and colonialism, as in the works of Kara Walker and Yinka Shonibare. ‘Afro-Surrealism’, he writes, ‘rejects the quiet servitude that characterises existing roles for African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, women and queer folk. Only through the mixing, melding, and cross-conversion of these supposed classifications can there be hope for liberation.’ The rhetoric of this manifesto may echo historical surrealist texts, but it also outlines a contemporary trajectory of straight, queer and feminist black artists and writers, ranging from Samuel R Delany to Toni Morrisson, and works as varied as Kehinde Wiley’s paintings and Wangechi Mutu’s collages.

Catriona McAra’s scholarly study of surrealist artist Leonora Carrington’s ‘haunting in the contemporary arts’ is a most welcome complement to general projects such as Polizzotti’s book (or Miller’s manifesto) in that it provides in-depth interviews and case studies of specific instances of Surrealism’s relevance in popular culture as well as contemporary art, literature and performance. By casting Carrington as a ‘medium’, the author moves away from the obsession with biographical narratives that has often shaped the reception of Surrealism more generally and Carrington’s work in particular. Instead, the author examines Carrington as a ‘context’ – comprising paintings, writings, personas, as well as the artist herself as both a real-life and a phantasised interlocutor – that has inspired a wide range of productions created in the past ten years or so. (The fact that Carrington’s enduring ambivalence towards her upper-class British origins constitutes a leitmotif of her work and life may explain the largely British and American constituency of McAra’s study.) When Carrington’s characters and universe are quoted directly, they appear as clichés waiting to be reinvested, whether with ‘narrative extravagance’ in Tilda Swinton and Tim Walker’s collaboration for i-D magazine in 2017 or through a more environmentally driven ‘harvest Surrealism’ in Double Edge Theatre’s mises en scène of Leonora’s World on a farm in rural Massachusets in 2018–19. The more ethereal ‘hauntings’ of Carrington as medium occur in less obviously theatrical formats, such as Lucy Skaer’s successive works inspired by her meeting with Carrington in Mexico (Leonora, 2006, and Harlequin is as Harlequin does, 2012). By playfully suffusing the composition and display of video, prints and found objects with magic and arcane elements, such works point to what McAra calls a brand of ‘esoteric conceptualism’ that appears to me as a fruitful model for moving away from the clichéd ‘surrealist-inflected image’ and for harnessing other processes and inspirations characteristic of broader surrealist legacies.

In her response to McAra’s questionnaire, curator Cecilia Alemani praises Carrington’s ‘world full of hybridity and transformation’: two ‘extremely timely’ ‘concepts’ that Alemani foregrounded in the Venice Biennale she curated in 2022 under the title of Carrington’s children’s book, The Milk of Dreams. There is no doubt that the metamorphosis and gender fluidity, as much as the grotesque aesthetics, that permeate Carrington’s work strongly resonate with the revolution brought about by trans theory and practice. Moreover, the appeal, for performance artists as well as contemporary authors such as Chloe Aridjis and Heidi Sopinka, of Carrington’s portrayal of human–animal hybrids – and relations among species – is grounded, as McAra demonstrates, in today’s ecological crisis. One of Carrington’s most influential books, The Hearing Trumpet of 1974, ends in an apocalyptic landscape transformation that directly evokes our climate crisis. While Ali Smith has called this novel ‘visionary’ (in her 2005 introduction to the book), McAra points out that Carrington’s environmental thinking also took activist forms; for example, from 1986 Carrington participated in the ‘Group of 100’, which campaigned for the protection of endangered species in Mexico and Latin America.

In a pornographic era where any sexual phantasy, it seems, can be satisfied with a few clicks, while our media-surfing relies on the succession of often violently clashing pictures and data, the artists discussed by McAra seem less concerned with the aesthetics of shock, desire or terror traditionally embedded in the surrealist image. Carrington’s work resonates instead with current interests in ecofeminism mingled with the occult, the magical and other repressed traditions. Though Carrington’s account, in the 1944 Down Below, of her psychotic breakdown and violent institutionalisation during the Second World War is no less terrifying than the wartime experiences that shaped her male counterparts’ surrealist deliriums, I would venture to suggest that the difference lies in its emphasis on survival. The ‘why do we care?’ that my students require me to answer is the ‘what does it matter?’ that Polizzotti sees as this new generation’s primary question, distinct from those posed by ‘the entire modernist enterprise’ (including Surrealism’s) who sought to reflect on ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What is reality?’.

Crucially, it is as a medium for ‘inter-generational’ conversations that Carrington emerges above all in McAra’s study. Carrington met the surrealists when she was 20 years old (and experienced for herself the movement’s ‘bullshit role for women’, as she would put it to Polizzotti) and died at 94, in 2011, after nearly 70 years in Mexico where she brought up her two sons while actively participating in her own circle of artists (including her close friend, the surrealist Remedios Varo, and the younger filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky). This longevity has allowed artists and scholars to cast the discovery of her work, often followed by a ‘pilgrimage’ to her house, as personal surrealist trouvailles, as well as to envisage her life as a feminist model of resilient creativity. Polizzotti argues that some of ‘the obstacles we now face’, which did not exist for the surrealists, make it difficult to continue ‘believing that solutions are even possible’. I would go one step further: have we arrived at a junction in which we are losing the possibility to even imagine another world? Whatever artist or movement we turn to, it looks like we need all the help we can get.

Mark Polizzotti, Why Surrealism Matters, Yale, 2024, hb, 232pp, £16.99, 978 0300257 09 0.

Catriona McAra, The Medium of Leonora Carrington: A feminist haunting in the contemporary arts, Manchester University Press, 2024, pb, 248pp, £19.99, 978 1 526177 45 2.

Anna Dezeuze is an art historian.

First published in Art Monthly 480: October 2024.