Feature

Warhol: Working-class Hero?

What if Warhol Cared? asks David Hopkins

What if Warhol cared? This question has been bubbling under for some time, not least in writings by Critics such as Thomas Crow and Hal Foster. His late ‘camouflage’ paintings, an enormous example of which appears in Tate Modern’s current Warhol exhibition, seem to ironise his own contention that both he and his works were all about ‘surface’.

Just as the colour in his early silkscreen paintings of celebrities such as Elizabeth Taylor seems to be an equivalent for cosmetics, so his later ‘camouflage’ pictures, which allude ironically to modernist abstraction, seem to imply a presence behind or beneath the surface. So, contra Fredric Jameson, did Warhol secretly adhere to a ‘depth model’ of the artist? And was he more concerned, more socially engaged, than conventional wisdom has it?

The evidence for a hidden Warhol – someone who was hardly the ‘machine’ he aspired to be – grows all the time. At the Tate there is a Double Elvis, in silver, in which two images of the gun-wielding star are presented side by side. One of the silkscreened images is much more heavily inked than the other and thus darker in tone, notably in the area of the star’s face. Given that a year later Warhol chose to use photographs of race riots in the American South as his subject, it seems likely that he was drawing attention to the black roots of Elvis’s cultural identity. l want to argue that Warhol didn’t simply register social spectacle impersonally, he passed comment on it. The reason this is often downplayed is that his means of doing so were disarmingly economical. Keep the basic image neutral, but overlay photographs of an electric chair with lavender or scalding-hot red. Let the ink supply run out in a sequence of Marilyns. There was no desire here for grand statements. Perhaps he tried to envisage emotions as a machine might – or someone from another (colder) planet – but the irony was there for a purpose.

If, deep-down, Warhol cared, it can also be shown that he was not quite as hung-up on up-to-the minute 60s consumerism as is often assumed. In fact he was frequently nostalgic, even anachronistic in his choice of imagery. His ‘Campbell’s Soup Can’ paintings bore a label design which had remained the same for 50 years. Indeed the older, reliable, design was chosen precisely at a time when the product was being re-marketed. Something similar applied to his paintings of Coca Cola bottles; cans were just about to take over.

Certain of Warhol’s images of celebrities speak more directly of what was then history, the outstanding example being the 1962 and 1964 film still homages to James Cagney. Indeed the more one thinks about Warhol’s early 60s output the more it becomes apparent that his use of photography as his privileged technical resource allowed for a form of historical self-reflexivity which had previously been unavailable to painting, except perhaps in the work of Robert Rauschenberg or certain British proto-Pop artists. In this respect, it is not only history as photographed but, reciprocally, the history of photography which closely informs Warhol’s practice in the early 60s.

Given this, it is remarkable that little has so far been made of the obvious parallels between Warhol and that most hardbitten of 40s New York tabloid photographers, Weegee.2 Harrowing scenes of death were Weegee’s stock-in-trade but even more conducive to Warhol would have been the fact that Weegee came from a similar Eastern European immigrant working-class background and that he had the same hankering after fame; his photographs often bore the stamp: ‘CREDIT PHOTO BY WEEGEE THE FAMOUS’. (In the late 50s and 60s, after a lifetime of hard graft, Weegee mingled, incongruously, with the stars in Hollywood and New York. Tellingly, he photographed not only the objects of Warhol’s fixations – Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy – but Warhol himself.) The Tate exhibition in fact contains two Warhol images which resonate strikingly with Weegee. One is Foot and Tire, 1963, a grim image of the sole of a shoe jutting out from under a lorry’s wheel, which revisits a Weegee photograph of 1938. The other is Black and White Disaster, 1962, an image of a body being carried from a burning building, which might be a macabre homage to one of Weegee’s pet themes. A whole section of Naked City – the book which made Weegee’s name in the late 40s and which Warhol would almost certainly have seen in his early years in New York after 1949 – was devoted to what Weegee termed ‘roasts’.

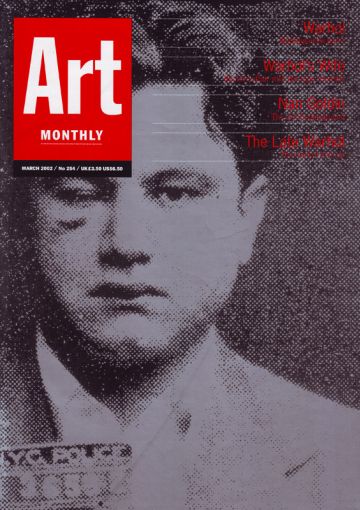

Further inflected by Weegee’s example, albeit at a greater remove, are the series of ‘Most Wanted Men’, originally produced to decorate a pavilion at the New York World’s Fair of 1964 but censored as potentially inflammatory. Given that they are rarely brought together, they rank among the highlights of the Tate exhibition. To some extent the project was an elaborate extrapolation from a spoof ‘Wanted’ poster produced by Marcel Duchamp in 1923, but it is fascinating that the images, which were lifted from a New York police department brochure of 1962, were of men whose crimes were committed as far back as the 30s. Just as Warhol, in blowing up these images, metaphorically dispersed the identities of men who were already socially invisible, so he appeared to invoke a past era of criminality. Inevitably one is drawn to reflect on a prior age when criminality and fame were brought into an alliance by the mass media and to think of Weegee’s photographs of dead gangsters and arrested criminals. (Warhol’s homage to Cagney again seems relevant here, as does an unusual Gangster Funeral silkscreen of 1968 which is also at Tate Modern.) At the same time, the ‘Most Wanted Men’ look back further to the inventories of criminal physiognomy compiled by 19th-century criminologists such as Alphonse Bertillon which stand at the origins of the archival uses of photography for purposes of social surveillance.3 More prosaically, the series also constituted an in-joke for Warhol and his gay friends. lt undoubtedly encoded a camp yearning for a past age of truly manly desperados.

Warhol’s exploration of the inextricable historical links between photography and criminal typology (or identity) provides an exemplary instance of his continuing relevance for artists. Whilst in many respects Warhol’s influence is ubiquitous today – think for instance of Gary Hume’s use of colour, Julie Roberts’s mid 90s imagery, Julian Opie’s graphic simplifications – it is his reflexivity about the discursive preconditions of photographic representation which possibly strikes the most resonant chord in contemporary practice. Take for example Douglas Gordon’s part-homage to Warhol, his Self Portrait as Kart Cobain as Andy Warhol as Myra Hindley as Marilyn Monroe of l996. In a seemingly throwaway mugshot image of himself in hastily-donned platinum-blonde wig, Gordon neatly collapses together a set of allusions not only to Warhol himself (both as lover of absurd wigs and as gender-bender, given his flirtation with drag) but also to criminality (Hindley’s notorious 1966 mug shot). Douglas thus performs a sequence of historical or discursive jumps which effectively recapitulates the complex sexual dynamics surrounding criminality as it is represented in the ‘Most Wanted Men’.4

This opens up a further, much neglected, aspect of Warhol’s own sense of his historically-conditioned relationship to a fellow artist, Robert Rauschenberg. Once again it is the history of photography which is at stake. In 1962-63 Warhol produced a sequence of silkscreen portraits of Rauschenberg (one of which hangs in the Tate show). The most intriguing of these, however, not least because of its title, is Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1963, in which, untypically, Warhol stacked several rows of disparate photographic images, relating to Rauschcnberg’s Texan upbringing, on top of each other.

The fame accorded to Rauschenberg by this title was implicitly linked with the ‘wanted’ designation applied to the silkscreened criminals during the same year. More specifically at issue was the fact that Rauschenberg – a newly famous artist-outlaw like Warhol himself – was widely known to be bisexual. The multivalence of the title is further extended by the fact that it constitutes a readymade with a pronounced photographic inflection; Let Us Now Praise Famous Men – James Agee and Walker Evans’s book of l941 – is possibly the best known documentary photo-essay of the 20th Century. The appropriation of this title was a master-stroke on Warhol’s part. The book had recorded the plight of Southern sharecroppers and their families in the American South during the Great Depression, turning lowly subjects into candidates for fame. (Think, for instance, of the ubiquity of Walker Evans’s photograph of the long-suffering Allie Mae Burroughs.) Warhol knew that Rauschenberg hailed from the South, and that, like Warhol himself (and Weegee for that matter), he came from a working-class background. But Warhol’s act of appropriation took in more than this. He knew full well that the apparently artless frontality of the silkscreen portraits that he was producing partly had their photographic forebears in Walker Evans’s square-on images of the rural poor. (By the same token, as has been argued, Weegee was a historical touchstone for the ‘Disasters’.) In the Rauschenberg portrait Warhol therefore aligned the historically-determined aesthetic co-ordinates of his practice with the experience of an emergent generation of economically aspirational artists, implicitly placing them in the context of a generational shift towards an American-style democracy in which gay working-class artists, like criminals or the rural poor, could potentially achieve fame.

More than anything the implications of Warhol’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men allow us to realise how well Warhol understood his historical relation to photography and, more importantly that, despite his apparent indifference to politics and his pathological fascination with capital, he nurtured an almost sentimental awareness of his class roots. This obviously underlines the notion of the hidden Warhol discussed at the start of this article. But it also prompts a return to the question of how such a Warhol might be relevant for contemporary practice. Put bluntly, much current art shies away from questions relating to its own historical embeddedness or historicity. Questions of class, although highly relevant for any discussion of 90s figures such as Mark Wallinger or Sarah Lucas, tend to be kept implicit rather than explicit (although Gillian Wearing’s practice, which in its continual probing of the intrusive or voyeuristic preconditions of lens-based media has a distant affinity to Warhol, might be seen as one prominent exception, not least in terms of a video-work such as Drunk, 1999, which places the sheer intractability of the socially dysfunctional centre stage).

My intention is not to make a covert appeal for a return to the post-conceptualist photo-based practices of the 80s, which frequently tended to be smugly knowing regarding questions of historical positionality. However it would be gratifying to see the development of more socially self-reflexive modes of artistic engagement. And in this respect a new reading of Warhol – who has ostensibly been a role model for artists ready and willing to capitulate to the spectacle – seems well worth positing.

1. Kirk Varnedoe, ‘Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962’ in Heiner Bastian Andy Warhol Retrospective, Tate Publishing, 2002, p42.

2. See my recent article ‘Weegee and Warhol: Voyeurism, Shock and the Discourse on Criminality’, History of Photography, vol 25, no 4, Winter 2001, pp357-367.

3. See Allan Sekula ‘The Body and the Archive’, October, Winter 1986, pp3-64.

4. For a fuller discussion of Douglas Gordon’s self portrait see my ‘Douglas Gordon as Gavin Turk as Andy Warhol as Marcel Duchamp as Sarah Lucas’ in Twoninetwo: Essays in Visual Culture, Edinburgh Projects (Edinburgh College of Art), no 2, 2001, pp93-105.

‘Andy Warhol Retrospective’ is at Tate Modern, London from 7 February to 1 April 2002.

David Hopkins is Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of Glasgow. His latest book is After Modern Art 1945-2000.

First published in Art Monthly 254: March 2002.