Feature

Videoscan

Video history – who needs it? We do argues Catherine Elwes

In the next month, the Arts Council will be releasing its long awaited History of British Video Art. Whether or not we need such a document might well be debatable since, like Michael Archer, I find students and indeed some artists both ignorant of and often uninterested in their artistic heritage.

Furthermore, there exists a generalised suspicion of any work done by videomakers whose age would naturally exclude them from the Young British Artist phenomenon. In viewing contemporary work, I often have the sense that I am being asked to join in the chorus of approval simply on the grounds that it has been executed by ‘fresh young people’. Youth no more guarantees artistic worth than does old or middle-age. But Michael Archer is right when he urges us to examine the differences between current practice and its antecedents rather than dismiss new work as derivative and retrogressive on the grounds that it’s all been done before. 1

I am also aware that my interest in history might be a sublimated wish to establish orthodoxies and nostalgically protect an area of specialisation called video art which has all but disappeared into the motley bag of tricks that today’s art producer performs with scant regard for formal considerations and a relaxed attitude to content. But again I am slipping into old fart mode and in spite of the exhaustion of viewing hours of numbing video clips from the various distribution agencies, I will attempt to define what I see as the nature of the practice we engaged in as video artists and the current condition of video in the repertoire of today’s practitioners.

When video emerged in this country in the early 70s, it shared with its American counterparts an euphoric rejection of both easel art and the conventions of gallery-based sculpture. The author had not yet died but a Marxist analysis of the art market soon dispensed with the art object now regarded as the ultimate saleable commodity underpinning the workings of venture capitalism. ‘Cultural workers’ engaged in process-based hybrid activities – mostly performance and installation – where they could sell their labour by the hour like any other member of the workforce. Independent film already had a well-established theoretical framework which was radicalising the analysis of narrative structures but video lent itself more readily to the politics of procedure that performance initiated. In fact one of the earliest uses of video was as an adjunct to performance. Artists like Tina Keane used a closed-circuit system to present a mediated view of the proceedings simultaneously with the live event.

The instant feedback of the video image made it an ideal medium of performance, as an element in the work itself, as a record of a live event and as a means of recording private or directed actions to camera. It had the added advantage of being virtually uncollectable as an object. It could be copied and distributed through the numerous artist-run workshops without ever being seen by a dealer. As a result, dealers and commercial galleries took no interest in video and it is only recently that the Tate has bought a tape, first asking the artist to sign the cassette.

Many early British video artists saw their practice as a direct challenge to the monopolies of the art market, but an even more important adversary was the monolith of broadcast television. Some adopted the strategy of working with community groups on specific issues and avoiding television altogether by distributing the work through the community and the unions. Others saw the work itself as an oppositional practice. In its constant references to process, the means of production and the specificities of technology, it challenged the illusionism of broadcast television and by implication, the dominant ideologies embedded therein. Paradoxically, this brought video back into the realm of art.

Stuart Marshall has argued that ‘modernist video’s’ insistence on the inherent properties of the medium, guaranteed it a place in the modernist mainstream.2 But video was hampered by the literal representation of the world that the technology imposed (digital processing was in its infancy). Unlike him, the artist was kept at a distance from the electronic processes – video could not be cut, scratched or painted. This led artists to ‘become embroiled in the practices of signification’.3

The early 80s saw the emergence of ‘New Narrative’ in video which combined the deconstructive eye of feminist art with a cautious use of narrative in which ‘no meaning is given or natural but is, instead, (seen as) the product of a signifying practice’.4 Television was no longer the bad object it had been in the 70s, and now became a source of representational models which could be transformed to reveal the workings of dominant ideology as well as propose redefinitions of the cultural stereotypes that television fictions enshrine.

Like film, video art was deeply concerned with issues of spectatorship, which in feminist terms meant the appropriation of the masculinity embedded in the eye, the look of the camera. More generally, it shared with performance a conviction that the meaning of a work was created by the spectator, or as Peter Kardia recently put it, by ‘the interaction between the position and place of the witnessing subject and the imaginative project embodied in a work.’5

Video art had its detractors. Although women artists in particular found the technical independence (no crews) that video offered conducive to the autobiographical, diary-based work that the ‘personal as political’ gave rise to, Martha Rosler cautioned against the narcissistic preoccupations this could degenerate into if ‘the attention narrows to the privileged tinkering with or attention to one’s solely private sphere, divorced from any collective struggle or publicly conjoined act’.6 Rosalind Krauss went as far as to accuse video of an inherent narcissism. Citing Vito Acconci’s masturbatory performances to camera, she describes video feedback as a closed system removing the utterances of artists from their own history and the complex socio-political present in which they exist.7 Instead, as Micky McGee put it, they indulged in the ‘futile desire to be simultaneously the subject and object of their own desire’.8 It is here that I want to return to contemporary work since I am often struck by the absence of political engagement at either a formal or strategic level. Video has developed an aesthetic of narcissism which plays to its audience’s vanities and aspirations in much the same way that advertising mythologises youth and material success for the purposes of selling consumer products.

I have seen innumerable works by young artists, often women, dancing provocatively to camera with motley soundtracks culled from the sexy familiarity of the pop archives or the emotional flights of the classics. Georgina Starr, Hilary Lloyd and Michael Curran have all shaken their rumps for art – a spectacle we have undoubtedly enjoyed. Mark Harris uses Mikhail Bakhtin’s evaluation of the carnival to suggest that such exuberant displays like medieval ribaldry might constitute an ‘irrepressible opposition to hierarchical institutions’.8 But video isn’t live, it is safely enclosed in the familiar box of the monitor or blown up into a pixilated mosaic that is more likely to produce a pleasurable stupor in its audience than incite them to riot. Georgina Starr dancing alone in a video vacuum relates only to the spectacle of her conventional beauty caught on tape like a million equivalents on broadcast television. She relates neither to her peers, nor to a political position, nor to a formal proposition which might illuminate her actions.

For the spectacle of a woman performing to take on a radical edge, she must abandon the safety of the mediated image and challenge an audience’s conventional responses with her unequivocal presence. If femininity is a series of acts or persona to be worn and discarded at will, the live performance more than anything disrupts the objectification of the camera’s eye. As Sally Potter has explained an audience is unable to ignore ‘the ballerina’s physical strength and energy which is communicated despite the scenario; the burlesque queen whose apposite and witty interjections transform the meaning of what she is doing and reveal it for the “act” it is; the singer who communicates through the very timbre of her voice a life of struggle that transforms the banality of her lyrics into an expression of contradiction’.10

It is not impossible for video to wield the disruptive force of a live performance. Annie Sprinkle’s Sluts and Goddeses of 1992 is a sexual tour de force wryly dressed up as a west-coastish primer for the modern woman. I regularly traumatise (and educate) my first year students with her demonstration of a multiple orgasm. The work never fails to send us into a lather of confusion. Are we witnessing pornography or a radical insistence on female pleasure? Who is in control of the image? Could Saatchi ever appropriate her performance for an advertising campaign? Am I risking my job by showing the tape on college premises? The image of the slightly overweight ex-porn queen taking her pleasure continually evades capture and like Carolee Schneeman before her, Annie Sprinkle confounds the socially acceptable manifestations of female sexuality.

Annie Sprinkle may be a hard act to follow, but younger artists have used sexuality to problematise dominant representations of human relations. Sam Taylor-Wood’s image of herself as Slut, 1994, shows the artist perfectly made up but ‘damaged’ by the signs of her own sexuality – a series of perfect lovebites decorate her neck. This use of ritualised and controlled mutilation is reminiscent of Gina Pane’s razor performances but it takes on a more interesting dimension in the younger artist’s work since it speaks of relationship, of desire and the primitive urge towards symbiotic union, with the consumption of the other as a necessarily violent act.

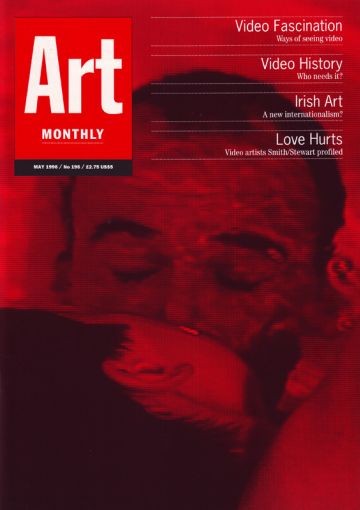

In Dead Red, 1994, Edward Stewart continuously swoops to cover Stephanie Smith’s face with lipstick kisses. Her face and neck slowly drown in the blood of his passion. The psychosexual dynamics of the heterosexual union are powerfully evoked in Stewart and Smith’s Mouth to Mouth of 1995 (see profile p.24). In a reversal of roles, Stewart lies helpless submerged in a tubful of water. He holds his breath. From time to time bubbles rise, this being the signal for Smith to lean over and perform an underwater kiss of life. She breathes for him, without her his life has no meaning and he literally and metaphorically ceases to exist. Here the work evokes the mother breathing for her infant son floating in the waters of her womb. The adult male discovers the terrible consequences of his own desire in an adult dependency on his mother’s successor in his affections. For me this tape illuminates Bill Viola’s desire to appropriate his mother’s death and his wife’s labour. The realisation of his own insignificance in the processes of life and death and the enormity of his emotional dependence on the two women elicits the response of art – an attempt through the image to control what nature and time do to our lives.

It may be that contemporary artists using video see little reason to connect to wider social issues. The retreat into narcissism may reflect a conviction that ‘we cannot even begin to think of counterposing alternatives to our current socio-economic order’. It might be a cynical pragmatism on the part of emerging artists who, aware of market forces, provide the goods for the sideshow culture that currently passes for art. Some artists are using video simply to play and prance in public. Others like Michael Curran and Stewart and Smith are exploiting the immediacy of the medium to de-stabilize our readings of homoerotic desire (Curran) and ‘normal’ heterosexual coupling (Stewart and Smith). However it is the recent work of a ‘mature’ artist which struck me most at the recent media festival at the ICA. Cordelia Swann’s Desert Rose, 1996, is a film about Las Vegas. It opens with familiar travelogue footage of the city – glittering casinos, hotels and neons. It is beautiful in the subjective, sensual tradition of independent film. But gradually the increasingly abstract patterns of light take on a more sinister aspect as a voice-over describes the hidden secrets of the town: nuclear tests in the 50s caused widespread damage to land, livestock, and individuals – including John Wayne who happened to be filming in the desert. The integration of image and narrative was a slow and measured process and as my preconceived readings of the glitter and glitz of the city dissolved, I realised that my own father had been a military observer of the Nevada nuclear tests and that, like Cordelia Swann, my own life may have been touched by the fall-out. I would like to see a video work reach this level of social engagement while demonstrating a rigorous understanding of the formal and communicative power of moving pictures and sound.

1. Michael Archer AM193.

2. Stuart Marshall, cataIlogue essay ‘Institutions/Conjecture/Practices’ in Recent British Video Onlywoman Press London 1993.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Peter Kardia AM193.

6. Martha Rosler statement made in a discussion ‘Is the Personal Political?’ ICA 1980.

7. Rosalind Krauss ‘Video: the Aesthetics of Narcissism’ in Video Culture, a Critical Investigation Visual Studies Workshop Press 1990.

8. Micky McGee ‘Narcissism, Feminism and Video Art’ Heresies 12 New York 1981.

9. Sally Potter catalogue essay ‘On Shows’ in About Time: Video Performance and Installation by 21 Artists ICA 1980.

10. Peter Kardia ibid.

Film and Video Umbrella distributes ‘Fresh’, 20 new artists’ work on video including Michael Curran’s L’heure autosexuelle and Smith/Stewart’s Dead Red. Mouth to Mouth is part of Instant exhibition at Bradford’s Gallery 2 to May 8. Film and Video Umbrella has just launched Never a Dumb Moment, a selection of fun-size video works by young international contemporary artists.

Catherine Elwes is a videomaker and teaches at Camberwell.

First published in Art Monthly 196: May 1996.