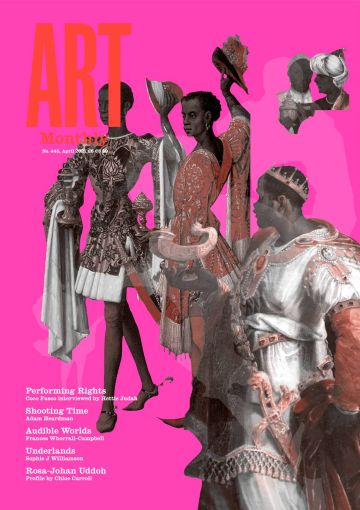

Feature

Underlands

Sophie J Williamson explores how artists are critically reconnecting to our ‘geological ancestry’

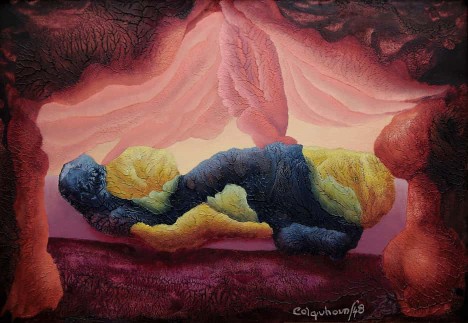

Ithell Colquhoun, Alcove II, 1948

For Sophie J Williamson, works by Mochu, Semiconductor, Larissa Araz, Alper Aydın, Ithell Colquhoun and others search for different ways to engage not only with the ‘critical zone’ of Earth’s surface but also the planet’s volatile core, enabling us to reconnect with our ‘geological ancestry’.

In author NK Jemisin’s dystopian trilogy ‘Broken Earth’, 2015–17, precarious societies struggle to survive amid regular apocalyptic cycles and periodic extinctions. Having previously plundered the earth’s resources – angering Father Earth, the sentient inner being of the planet – and provoked its now constantly agitated seismic activity, the ruling elites exploit a minority race, the Orogenes, which, as the name implies, possess orogenic powers: their senses can probe down into the earth’s crust, diverting kinetic or thermal energies to calm and quell shakes, softening the collisions of tectonic plates. A thinly veiled analogy of embedded colonial oppression – the Orogenes are both feared and ruthlessly exploited – the narrative must also be read as a response to the reluctance of society to attune itself to earthly languages; wanting to extract, destroy and control, rather than seek symbiosis with the inorganic. Against the background of the Randian repercussions of the current pandemic, and the fragility of ecological hope in the face of the changing winds of party politics in the most powerful nations, ‘Broken Earth’s analysis of humanity’s cut-throat survival tactics slices closer to the bone than most.

Learning new ways to inhabit the Earth is our biggest challenge; Bruno Latour argues that ‘bringing us down to earth’ is the new political task. But how do we do this when the earth below our feet seems so unknown, impenetrable beyond the barrier of urban concrete and previously assumed rules of engagement with the planet? In Timothy Morton’s podcast series The End of the World Has Already Happened, he admits that the overwhelming reports that we hear of climate change are enough to cause us to curl up into the foetal position and cry: a reaction, he says, that is perfectly reasonable. In A Billion Black Anthropocene or None, 2018, Kathryn Yusoff debunks geological conceptions that have rendered human society and inorganic matter a simple binary: geology is often assumed to be ‘without subject (thing-like and inert), whereas biology is secured in the recognition of the organism (body-like and sentient)’. Instead, she argues that geology inherently carries with it the violence of colonialism and capitalism, and while the exact moment of the Golden Spike marking the beginning of the Anthropocene is debated, she writes that it is ‘an inhuman instantiation that touches and ablates human and non-human flesh [...] It rides through the bodies of 1,000 million cells: it bleeds through the open exposure of toxicity, suturing deadening accumulations through many a genealogy and geology.’ How do we transcend what she refers to as this ‘shock and guilt’ in order to act? How dowe relate the corporeal life of the planet to our own, without losing sight of agency, of the personal, so as to rebuild a stabilising kinship with the geological?

From the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh to Arsan Duolai, Hades or Abrahamic hell, the cavernous depths below the earth’s surface have been feared throughout human history. And while modern science has looked out to the cosmos to learn about who we are, the world below our feet remains a dark matter closer to home: unknown, unseen and ominously quiet. David Attenborough’s honeyed voice-over, in A Perfect Planet, tells of us of life’s genesis erupting from the earth’s core: ‘Volcanoes are certainly destructive, but without these powerful underground forces there would be no breathable atmosphere, no oceans, no land, no life.’ This seismic ‘underland’ is our life support system, yet it is nevertheless mistrusted. Contemporising the ubiquitous underworlds of folklore and religious fables, Mochu’s performance-lecture Toy Volcano, 2019, uncovers the dread of the unknown darkness below embedded in the popular subconscious. He narrates a story of legendary rock formations, sealed off from visitors by earthquakes in an unnamed valley. Immortalised in fan-fiction manga animations and B-movie horror films, the tales try to make sense of mad geologies and ‘portable holes’, calling on geotrauma therapists, archaeologists, miners and volcanologists to unravel the manifold interpretations of a snapshot of the earth’s evolution. Toy Volcano reveals speculative horrors and our fraught relationship with geology via suspect materials, the fantastical physics of manga animations and trypophobia: the fear of holes. While staying in Cappadocia, in Central Anatolia, the film location for Mochu’s unnamed valley, I found myself nervously venturing into deep mountainside crevasses. I was reminded of Robert Macfarlane who, in Underland, describes how his heart hammers a warning in his ears, the ‘weight of rock and time bearing down’ on him: rock formations and ruckles might hold their position for tens of thousands of years, but an earth tremor might reorder these structures in an instant. These deep-time openings become the protagonists of Mochu’s fictional world: the mountain is a cocoon housing a writhing mass of volcanic worms and the unruly holes take on a predatory, parasitic body-snatching life-form, attracting human prey into their depths.

Mochu’s performance was commissioned as part of Ashkal Alwan’s ‘Home Works 8’ forum before what became known as Lebanon’s October Revolution erupted, filling the streets with fire blockades, protesters and water cannons. The long-anticipated uprising found its tipping point in tax hikes, while at the same time uncontrollable wildfires ravaged the countryside and ‘shadow economies’ suffocated coastlines with dumped waste, visible scars of the impact of capitalist greed and corrupted human interests. Yusoff argues that geology is neither politically nor socially neutral, that such colossal shifts like these are caused by capitalism and colonialism which directly impact our ecosystems, subsequently leaving a geological mark on the ‘Critical Zone’ of the surface of the planet. I finally saw the performance a year later, this time amid the global sense of existential uncertainty that has defined the Covid-19 pandemic. As Mochu’s manga official, battling the geological parasite, disintegrates into his new, holey existence, he observes: ‘My skin is a green screen, an invitation for contaminations. Now the ethereal has to be turned material [...] The worms have begun their work.’ Humanity’s ravenous poisoning and plundering of the land is reversed. Two-thousand miles away, meanwhile, anthropocentric global warming melts the permafrost across the Siberian tundra with terrifying speed; the billions of tons of carbon suspended in its frozen organic matter will be released into the atmosphere, rapidly suffocating existence as we know it. Earth is turning our weapons of destruction against us.

Closer to home, Semiconductor’s All The Time In The World, 2005, animates Northumbria’s landscape to the rhythms of the geological activity below the surface. Quintessential British hillscapes are thrown into disturbing disruption as the data of seismic activity, which has shaped and formed the land over millions of years, is played out at the speed of sound; frenetic vibrations quake and shake the landscape like an elastic drumhead. When it finally halts, the disruption remains uneasy and the image of tranquil rolling hills is exposed as only a fleeting – and precarious – geological moment. Tectonic movement continues out of sight, below, slowly building tension. How do we, like Jemison’s Orogenes, attune ourselves to these rhythms to find a harmonious balance? As Anna Tsing et al write in their Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, the next great extinction comes not from an asteroid from outer space or the geological beyond our control, but from industrial overproduction; the ‘Great Acceleration’ of the Anthropocene is the result of numerous ‘small and situated rhythms’, deadly in their accumulation. A recent article in Nature, for example, carrying the self-explanatory title ‘Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass’, pointed out that global manufacturing produces mass equal to every living person’s body weight every single week and, what’s more, the weight of the world’s plastic alone is now double that of all animal life on earth. For generations, ecology activists have pleaded for us to slow our consumption of the planet’s resources, without success. In his 2018 book Down to Earth, Latour argues that the perspective of the global – the view solidified in popular consciousness of the planet as a falling body amongst others in the infinite universe of Galilean objects – grasps all things ‘from far away, as if they were external to the social world and completely indifferent to human concerns’. Humanity has seen the planetary from the viewpoint of space, a globe to be capitalised in a universe waiting to be conquered. Latour argues that this has caused us to become detached from the vital planetary relationships that make life on Earth viable. ‘Little by little,’ he suggests, ‘it has become more cumbersome to gain objective knowledge about a whole range of transformations: genesis, birth, growth, life, death, decay, metamorphoses.’ Since mobilisation is not possible as long as nature is conceived of in the abstract, we need to resituate our concept of ‘homeland’, linking ourselves not to false notions of nation states, but to a soil – a Heimat, as Latour writes – with all the dangers that link soil and people.

While staying in Turkey, I felt the strength of this affinity among the people I met. As with so many countries in the Middle East, wars and pogroms have uprooted populations in Turkey time and again, creating strong bonds to the soil from which they were borne or from which they are denied. A profound closeness to the land is palpable, for example, in Fatmas Bucak’s studies of borderland materialities, Kerem Ozan Bayraktar’s micro and macro journeys and transformations of dust, Canan Tolon’s fragmentary landscapes, the absences and destructions in Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s installations, or Larissa Araz’s fig tree growing from the seeds in the stomach of a corpse in an unmarked cave grave. In Cappadocia, geological form is palpably intertwined with the daily activities of its inhabitants, both human and non-human. Created out of the ash from two supervolcanos ten million years ago, the soft tuff rock has eroded into cavernous valleys and – easily carved by hand – was populated by cave dwellers. Entire populations would retreat underground, living a secret life below the surface in the vast networks of tunnels and caverns: refuges from wars, colonisers and persecution. Alper Aydın lives on the shore of the Black Sea, where his work – and his daily life – unfold within the rhythm of the land where he was born. Commissioned to make a new work in the Cappadocian valleys for Cappadox 2017, Aydın’s performance Shelter saw the artist meld himself into this unfamiliar land in order to speak to it. Almost naked and using only his hands, he sculpted a dome around himself with mud hollowed out from below his feet until he was completely encased in his earthy subterranean sanctuary. ‘Can we perceive cosmos through looking at the depths of the earth, the world under our feet?’ he asks. Aydın’s earthy hideaway echoes 17th-century Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher’s concept of the ‘geocosm’, a geological womb, as described in his lavishly illustrated Mundus Subterraneus. Kircher saw the ‘underworld’ as a macro-cosmic architecture that parallels the microcosm of the human body, a geological cosmos entangling telluric, organic and human worlds: ‘a harmonically structured organ, dark and full of wondrous creatures, animated by heat diffusing throughout it, connecting the terrestrial with the divine’. Aydın builds a cocoon around himself to nurture the symbiotic and, through the seeming simplicity of his action, to interact with the land through its natural properties, growing into it, to emerge once again. Like the mathematician’s insistence that a mug and a doughnut are topologically identical, Aydın moulds the land anew, transforming it out of itself, taking and adding nothing, enabling a dialogue whilst also letting it slope back afterwards to its topological beginnings. Attending to what Latour refers to as earth’s internal ‘collectivities’ – the collective interactions between all matter – with sensitivity to human actions is, he argues, vital in order to grasp the earth’s rhythms from ‘up close’ and to become truly ‘Terrestrial’. His argument builds on those of theorists such as Donna Harraway and Tsing, whose writings over recent years have disassembled the image of the wholly singular Earth. Physicist and philosopher Karen Barad invokes quantum field theory to reveal Earth’s haunted landscapes as strange topologies: ‘Every bit of spacetimemattering is ... entangled inside all others.’ With this resituated way of seeing the planetary, Latour proposes that the new distribution of these metaphors and sensitivities are essential to the recovery of the planet and the reorientation of political affects.

In Ithell Colquhoun’s enchanting prose on life in rural Cornwall, The Living Stones, she writes, ‘The life of a region depends ultimately on its geologic substratum’; characterising the land, it sets up a chain reaction for everything else that lives there. The inherent connection between mineral and organic bodily forms was an enduring preoccupation for her. Seeking the pliability of the in-between, a slippery space between two worlds unnecessarily delineated from one another, for Colquhoun volcanoes, caves, rock pools and natural springs are permeable points in the ever-transient membrane between natural, human and spirit worlds. In Scylla, 1938, one of Colquhoun’s most loved double-image paintings, one’s eye drifts from seeing a pair of legs in bathwater to two craggy pillars harbouring a sea cove, a clump of seaweed or a flare of orange pubic hair lying conspicuously between the two. Her images of these liminal zones oscillate between the languages of flesh and minerality, a momentary blurring between the organic and non-organic, the living and the dead – a gateway between worlds. In lesser-known works on paper, Colquhoun finds meaning in the natural behaviours of her materials: landscapes out of the smoke marks or geological formations traced among the impurities of a blank sheet of paper.

These transformations reveal her dedication to tuning into the pre-existing language of the planet’s matter, whether it is graphite dust over a page or stalagmites across a speleothem. Roger Caillois would argue that, ‘being himself lacking in density, the last comma into the world’, it is merely the human condition to see our likeness in nature. In his stunning illustrated narrative on the subject, The Writing of Stones, he gruesomely interprets, in jaspers and agates for example, ‘an empty socket with a freshly removed orb dangling like wet rag [...] gnarled and ringed phalluses, swollen and purple, without their foreskins, the glans all wrinkled [...] rumbling innards, excited vulvas, striated tendons; pale partial globes jointed like the knees and elbows and hips of celluloid dolls’. He writes that there is no ‘site in nature, history, fable, or dream whose image the predisposed eye cannot read in the markings, patterns, outlines found in stones’. Colquhoun’s eye isn’t one of apophenia, though; it is not a correlation she depicts but a true sameness.

Her works are perhaps more akin to the mythological petrification of Medusa and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, or the Cornish folklores of Colquhoun’s nearby Merry Maidens stone circle and the Nine Maidens of Boskednan monoliths. Yet her works don’t seek alchemical transformation but instead present a worldview that they are equally live. In paintings such as Alcove I, 1946, and Stalactite, 1962, she travels into the geological underworld while simultaneously delving through stratum of subcutaneous layers to reach internal organs, as if both are made of the same materials but of different longevity: one fleshy, the other leaden. Rocks are bodies, bodies are rocks. For Colquhoun, to venture into the darkness of Vow Cave was for her to climb into the womb of her local landscape: finding a personal heritage, stretching back some 4.5 billion years, throughout all its organic, sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous transformations. As her paintings gaze out to the world from their cavernous underlands, the human and the geological amalgamate to become one: the body of the earth.

Colquhoun writes, ‘the structure of its rocks gives rise to the psychic life of the land code on granite, serpentine, slate, sandstone, limestone, chalk, and the rest [...] each being coexistent with a special phase of the earth-spirit’s manifestation’. The sense of conscious thought entangling with mineral existence is often echoed by those seeking an affinity with the land. Ursula K Le Guin’s admission, for example, that she is ‘just mud’, impressionable and yielding, in her text ‘Being Taken for Granite’, evokes the emotional affinities to mineral existences and their personalities. ‘One’s mind and the earth are in a constant state of erosion,’ Robert Smithson wrote, ‘mental rivers wear away abstract banks, brain waves undermine cliffs of thought, ideas decompose into stones of unknowing [...] The entire body is pulled into the sea cerebral sediment.’ Even after determinedly crediting his mineral readings to the ‘willing eye’, Caillois can’t help but speculate that this inextricable complexity of interactions over millennia could perhaps be owed to a larger cosmic consciousness, and that it is natural for humanity as its heir to recognise ‘through their very failure, a glorious way ahead’.

If, as these artists and writers tentatively propose, we as a species are able to find a bodily and cerebral entanglement with our geological ancestry, what then of the future? ‘Her tongue is as long as time. Not death can languish, no quake can slide her,’ narrates the disembodied, ethereal voice of Ben Rivers’s 2019 film, Look Then Below. Deep below the earth’s surface, hidden in a network of glowing caves, human remains and crystal formations take on an uncanny shared sentience. While Mochu and Aydın’s Cappadocian geologies are made of the deaths of supervolcanoes, these caverns, of the Wookey Hole Caves, are a graveyard of another kind. Over the millennia, marine organisms accumulated in their trillions into limestone tombs: ancient seabeds formed of the compressed bodies of crinoids, coccolithophores, ammonites, belemnites and foraminifera. In Underland, MacFarlane describes this corner of Somerset as a ‘dance of death and life’: transforming minerals from the water to create ‘intricate architectures’ of their skeletons and shells, the sea creatures later become rock that is eroded away to again nourish the sea. A life cycle of multispecies in which ‘mineral becomes animal becomes rock’. Stone Tape Theory, popularised by 19th-century psychics, hypothesised that mental impressions could be imprinted onto rocks and other items through projected energies, recorded in a mineral language and ‘replayed’, like a tape recording, in the future under certain conditions (a pseudoscience also deliberated over by Mochu’s anime investigators). Look Then Below listens for the secreted voices of those bodies embalmed in their rocky reality.

Caves perhaps have much in common with black holes in cultural consciousness: powerful and deadly, drawing matter, energy and bodies into an infinite darkness. Conversely, NASA astronomers recently discovered a supermassive black hole believed to have sparked the births of stars millions of trillions of miles away, across multiple galaxies, nurturing them with hot spewing gas, energising jets of particles in the surrounding matter. Both nourishing and feeding on their surroundings, the caves of Look Then Below seem to both swallow time and emit renewed energy into a thriving pulsating ecosystem of the glowing rocks. Human remains merge with their deep-time geological cohabitants, compacting eras into an eerie unison. Organic bodies discarded, surplus to requirements, sentience has been absorbed into a mineral existence. In his writing on solidarity with the non-human, Timothy Morton writes: ‘I cannot speak the ecological subject, but this is exactly what I’m required to do. I can’t speak it because language [...] is fossilised human thoughts.’ Just beyond the grasp of our recognition, Rivers’s effervescent caves invert Morton’s predicament: intelligent thought emanates from the glistening rocky walls, sometimes legible through echoed whispers, sometimes murmured in vibrations beyond our linguistic limitations, speculatively decoding the language written in these rocks, ‘bubbling out of the limestone by ancient fluids’. Beyond the life of our species, the hidden geological voices speak from the deep past reaching out to an intelligent being somewhere in the deep future, or a different temporality altogether, at once existing in the past, present and future.

It is among the crystal depths of cavernous underlands that Jemison’s survivors similarly find sanctuary. When her future land thrashes about angrily, the Orogenes ‘sess’ downwards, deep into the bedrock; they take stock, sensing the lay of the land below, calmly steadying and soothing the reverberations as they find a shared affinity with it. Perhaps we too can find ways to align ourselves with the geological, to soothe a possible symbiotic future. As Michael Serres has written, within the underland, ‘Thousands of materials hold millions of exchanges and conduct billions of reciprocal transformations’, and as such the cave demonstrates how we and other living entities are collectively formed: the ever-transforming fabric of the planet. He continues: ‘I too am a diamond, made of hard carbon, occasionally pure, transparent, or grainy [...] emanating from the various things in the world as well as thousands of people and living entities one comes into contact with. I too am a cornucopia.’ One of my most memorable studio visits entailed being huddled in a storm drain with Augustas Serapinas. From this dark retreat from the outside world, we could contemplate the wonders of the outside without the noise of contemporary life. We were surrounded in the darkness by mud, stone and water, and the other end of the tunnel opened onto a bright sunlit river flowing past, preventing our eyes from adjusting to the dark. I felt like we were inside a shared earthly consciousness.

Sophie J Williamson is a programme curator (exhibitions) at Camden Arts Centre, London.

First published in Art Monthly 445: April 2021.