Feature

Troublemaking

Francis Frascina reconsiders conflicting debates about female pleasure and female violation in cultural representation

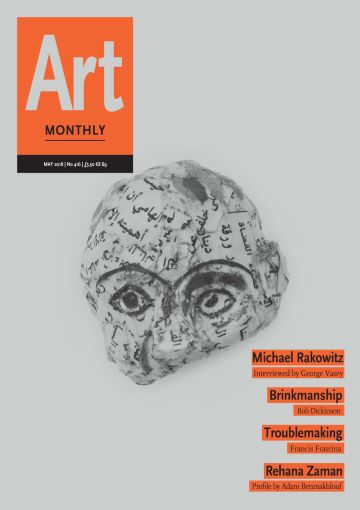

Dori Atlantis, Cunt Cheerleaders, 1970

I want to consider, with reference to feminist art practices, Jacqueline Rose’s recent question: ‘How can we acknowledge the viciousness of sexual harassment while leaving open the question of what sexuality at its wildest – most harmful and most exhilarating, sometimes both together – might be?’ Readers of Rose’s earlier texts, and those by Barbara Johnson and Carole S Vance, will know that to ask this question is to relive conflicting debates about female pleasure and female violation in cultural representations, particularly from the 1980s and early 1990s, albeit in a newly digital, volatile and often vitriolic social-media environment.

Of course, the contemporary context is fraught with difficulties. One well-publicised example is an event related to Sonia Boyce’s retrospective at Manchester Art Gallery (Interview AM415), which included an invitation to make a new work by reflecting on the 18th and 19th century galleries. Since last summer, this project involved Boyce holding sessions with a range of gallery workers to discuss processes of curatorial selection and the politics of representation. On 26 January 2018, Boyce invited five performance artists who, together with the participating audience, were asked ‘to respond artistically’ to works in these galleries, culminating in the temporary removal of JW Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896. This act was partly designed to prompt a debate about the objectification of women in artworks that normally adorn galleries and museums without exciting question or protest. Except, as is often forgotten, by the activities of feminist networks and organisations ranging from Women Artists in Revolution, Ad Hoc Women’s Artists Committee, and Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation in 1969/1970 to the Guerrilla Girls (Interview AM401) in the 1980s and the Women’s Action Coalition, which was founded in 1992. These groups’ agendas were to critique not only artists’ objectification of women’s bodies and the lack of women’s representation in galleries and museums but also discrimination and sexual harassment in the art world. Aptly, one of Jenny Holzer’s Truisms, ‘ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE’, originally publicly displayed on an enormous electronic message board in New York’s Times Square, is now plucked from 1982 as a reminder of the contemporary currency of past struggles, which – let us remember – were subjected to a backlash during the Reagan and Thatcher eras and beyond.

Manchester’s Waterhouse painting is based on a narrative from Greek mythology. Hylas and his male lover Heracles were Argonauts sailing with Jason in search of the Golden Fleece. On making landfall, Hylas was sent with a pitcher to search for fresh water and came upon a spring where naiads, the nymphs of fountains and streams, were bathing. In the painting, he is being hypnotically drawn to a watery death by the nymphs, captivated by their desire for the handsome youth. The erotic and gendered symbolism of the pitcher, which Hylas holds, and his search for fresh water are familiar to audiences used to decoding symbol systems in Dutch 17th-century and French 18th-century paintings: moralising warnings, often bawdy, about human vanity and carnal desire in a world of bourgeois ideals. Yet it could be argued, from radical feminist perspectives rooted in debates about ‘desiring and being desired’, such as those informing artworks by Cindy Sherman and Hannah Wilke in the 1970s and 1980s (see ‘Object/Self’, AM375), that readings of the painting in terms of the sexual power, pleasure and agency of the young women are as viable as those stressing liberated homoeroticism or the oppressive patriarchal gaze. Depending on the viewing subject, all three readings are defensible, separately or together, as established by theories and art practices resulting from, for example, discussion of Laura Mulvey’s essay from 1975 ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, which she radically developed further in her 1981 article ‘Afterthoughts’.

With all the advantages and disadvantages of ‘relational aesthetics’, Boyce’s orchestration of a dialogue and the subsequent temporary removal of the Waterhouse painting were met with press claims, many by men, of ‘censorship’ and an imposition of ‘political correctness’. Other paintings were cited in articles and the online conversation #magsoniaboyce, including Henrietta R Rae’s Hylas and the Water Nymphs, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1910, as though confirmation that women were/are complicit in representations of their own objectification and/or that feminist moralising was/is hypocritical. In applying a question asked by Rose – specifically about why Harvey Weinstein’s sexual harassment of women was turned into front page news with endless photo spreads of his female targets – we might also ask whether the proliferation of press images of the Waterhouse painting and other examples of nymphs and nudes ‘weren’t so much designed to provoke outrage or a cry for justice as to grant the voyeur his pleasure’. In this pleasure, too, patriarchal power lies. Those who protest at what they call feminist ‘censorship’ and ‘political correctness’ to claim a sense of ‘victimhood’ (the pathetic male complaining about ill-treatment by feminists) have, as Barbara Johnson argued in 1995, an investment in a model of patriarchal cultural authority where women’s ‘muteness’ is central to ‘control over the undecidability between female pleasure and female violation’ in representations.

From October 2017 onwards, sexual-assault allegations not only in Hollywood but also in the art world (see Jennifer Thatcher’s feature ‘No Surprises’ and Editorial AM414) made #MeToo – which was originally created by Tarana Burke in 2007 to draw attention to sexual violence against women of colour – go viral, particularly in the US. The pace of dialogue and revelation was so intense that by February 2018 Verso published Where Freedom Starts: Sex Power Violence #MeToo, an e-book collection of essays. Further, in early 2018 the shocking extent to which sexual abuse, exploitation and violence also characterised processes of ‘disaster capitalism’ was revealed to permeate international aid agencies with, for example, starving women in Syria subjected, since 2015, to ‘sex for grain’ demands. The same women were and are as likely to suffer as ‘collateral damage’ in extra-judicial killings by bombs or missiles deployed by drones – ‘piloted’ remotely from Lincolnshire, Texas or Nevada – that target ‘terrorists’, including British and American citizens, in Syria whatever their nationality (as they have for the past decade in Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Yemen).

The perverse politics of drone deployment and resultant subjectivities are represented in artists’ films such as Omar Fast’s 5,000 Feet is the Best, 2011 (Interview AM330), and Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun, 2015 (Interview AM373), and in photographs by Trevor Paglen and Edmund Clark. Yet Syrian women who face sexual harassment from aid workers and/or death from the air have little time to consider the contradiction that the UK government has spent £1.75bn on armed air missions in Syria and Iraq since August 2014, largely at the behest of the US, at the same time as spending millions of pounds on humanitarian relief in the same area. Although the budget for the bombs, unsurprisingly, exceeds that for aid, violent threats to women come, without warning, from the results of both. My point, to paraphrase Holzer’s artwork, is that the abuse of power comes in various guises.

In the press, the temperature was turned up on 9 January 2018 when 100 French feminists published an open letter in Le Monde criticising recent developments in #MeToo for puritanism, prompting a purge of visual imagery across a range of media and creating a climate of self-censorship for writers, filmmakers and artists. Responses, largely from the US, alleged that their French sisters were apologists for rape, had internalised misogyny, and were unable to understand contemporary women’s issues because they were over-privileged and stuck in the 1960s and 1970s. The heat of the exchange can be exemplified by supporters of #MeToo who, consistent with their attack on the writers of the Le Monde letter, had accused Margaret Atwood, the Canadian author of The Handmaid’s Tale, of being a ‘Bad Feminist’, prompting her response, published on 13 January in Canada’s Globe and Mail, ‘Am I a bad feminist?’.

This furore is rooted in previous culture wars: feminist arguments for and against publications by American writers Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon, from the 1970s onwards, on what they argued was the inseparable relationship between sexism in society and the pornography industry. Dworkin and MacKinnon argued that the latter, where the objectification of women is turned into a male-driven marketable socialisation of exploitation and violence, is a direct consequence of misogyny, oppression and inequality in contemporary societies. Arguing that pornography is a civil-rights violation, they advocated that the law was the most effective route to achieve an end to men’s domination, harassment and violence in everyday life. Some feminist dissenters regarded their views about masculinity, and male desire, as essentialist (echoing debates within feminism generally, and in art practice specifically, about essentialism and social construction) and their legalistic solutions as too authoritarian. Rose, for example, notes MacKinnon’s fear that without bringing sexuality within the remit of the law (directly related to gender inequality) it will ‘become a law unto itself’. However, for Rose this very phrase may describe ‘what sexuality is’, which is consistent with Simone de Beauvoir’s existentialist feminism where woman is not ‘born’ but ‘becomes’ through experiences and choices in her attempt to open up a space for the freedom to flourish in a hostile patriarchal society: ‘womanliness’ as masquerade, as multiple personas exemplified in Renate Bertlmann’s Transformations, 1969/2013, Marcella Campagnano’s The Invention of Femininity: ROLES, 1974, Alexis Hunter’s Identity Crisis (maquette), 1974, Martha Wilson’s A Portfolio of Models, 1974/2009, and Cindy Sherman’s ‘Untitled’ series of the 1970s. Rose argues that for ‘psychoanalysis, sexuality is lawless or it is nothing, not least because of its rootedness in our unconscious lives, where all sexual certainties come to grief. In the unconscious we are not men or women but always, and in endlessly shifting combinations, neither or both.’

Historical divisions in the American feminist community, inseparable from intense culture wars in the 1980s and 1990s, can be exemplified by the edited collection Caught Looking: Feminism, Pornography and Censorship, 1986: ‘We want to be safe from attack and abuse, in our private lives as well as in the public sphere, but we don’t want that safety at the cost of challenge, risk, exploration and pleasure. Safety and adventure represent conflicting demands: the relationship between the two, and how to negotiate it, is a key issue in the current debate.’ In 1991, the British-based Feminists Against Censorship published Pornography and Feminism: the Case Against Censorship, opening with an extract from Caught Looking, including this quote. They warn against the dangers of one group of women imposing control and regulation of imagery and notions of pleasure and desire on another less privileged group while missing the ‘real battle’ against public and private harassment and violence, unequal pay structures, and lack of opportunities for girls and women.

Here, Carole S Vance’s anthology Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, 1984, marks out a difference with the feminism represented by Dworkin and MacKinnon, as does her ‘The Pleasures of Looking’ in the influential anthology The Critical Image, 1990, edited by Carol Squiers. Vance’s critique of the Attorney-General’s (then Edwin Meese) Commission on Pornography, 1985-86, which she argued was an ideologically driven rumination about the unruly power of visual imagery, echoes Rose: ‘If we remain afraid to offer a public defence of sex and pleasure, then even in our rebuttal [of the Meese Commission and censorship] we have granted the right wing its most basic premise: sexuality is shameful and discrediting.’ Vance argued against fixed notions of sex and gender identities, as did Judith Butler in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, also published in 1990. Important legacies of Butler’s text open up space for displays and incisive reading of subversive images such as those in ‘Undercover: A Secret History of Cross-Dressers’ at The Photographer’s Gallery (February-June 2018), which represent contrasts and conflicts between the law and clandestine pleasure.

The Meese Commission on Pornography, as with attempts to censor ‘Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment’ in 1989, US senators’ attacks on Andreas Serrano’s 1987 work Piss Christ in the same year and Senator Jesse Helms’s concerted efforts to cut public funding for avant-garde art in the 1990s (Artnotes AM129, AM162), are examples of what Johnson refers to as the ‘official structures of self-pity that keep patriarchal power in place’. This is populist self-pity as excessive, self-absorbed unhappiness over perceived ‘victimhood’: conservatives claiming to be the victims of sexual and gender effrontery by, for example, feminist artists, filmmakers, educators and writers for whom there is an officially allocated position and condition. For Vance, when official structures such as the Meese Commission present a ‘rigid seemingly impenetrable symbolic and emotional facade’, this facade can be radically undermined ‘by insistently confronting it with what it most wants to banish – the tantalising connection between visual and sexual pleasure’. Earlier examples of such connections are the Feminist Art Programmes at Fresno and CalArts between 1970 and 1975, represented not only by Judy Chicago’s Red Flag, 1971, but also by Cay Lang, Vanalyne Green, Dori Atlantis and Sue Boud as Cunt Cheerleaders, 1970, who in pink and red satin outfits performed audacious routines for visitors to the programme. The installation and performance art of Womanhouse, too, in its one-month-long existence in an abandoned house in residential Hollywood in early 1972, confounded normalised controls over ‘the undecidability between female pleasure and female violation’.

Adrian Piper’s three-piece Political Self-Portrait, 1978-80, which comprises #1 Race, #2 Sex and #3 Class, represents a dialogue on constituent parts of identity formation (see Reviews p29). These were later emphasised in Tarana Burke’s 2007 stress on the necessity for a community space to publicise acts of sexual violence that are always within socio-economic, not solely personal, situations and by bell hooks’s discussion of the same in terms of constructions of black masculinity. In her 1994 essay ‘Feminism Inside: Toward a Black Body Politic’, bell hooks radicalised accounts of the relationship between struggles for African-American civil rights, where changes in the law might guarantee racial equality, and ‘black masculinity’, where oppressive patriarchy and violence to women have no racial divide. For hooks, racial equality does not necessarily guarantee sexual equality: even in communities already racially and economically oppressed, the abuse of patriarchal power comes as no surprise.

In ‘Feminism Inside’, hooks argued for the pursuit of pleasure, desire and transgression ostensibly for representations of the male black body (and by implication the female black body too) ‘that do not perpetuate white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’. This will not happen, she posits, ‘unless we change the way we see and what we look for’, with a stress not on the image-maker but on the viewing subject: ‘the perspective, the location from which we look and the political choices that inform what we hope those images will be and do.’

Similar arguments are applicable to the white body. In Helen Chadwick’s The Oval Court, which was part of her ICA installation ‘Of Mutability’ in 1986, she used 12 life-size images of her naked body in order to ‘open up a territory for desire, how to depict desire and physical sensation and pleasure’. Although she thought this was a ‘tight-rope act’ in the midst of feminist disagreements over, for example, Dworkin, MacKinnon and the Messe Commission, Chadwick attempted to make images of the body ‘that would somehow circumnavigate that so-called male gaze’. She wanted to open up a space for ‘the woman as the subject of feeling’ not simply to produce a work to be read ‘as a series of objects or symbols’. This proved to be so difficult in prevailing conditions of reception, including hostility from some feminists (for whom absolutely no representation of the female body was possible), that Chadwick shifted to more metaphorical work reliant on the political consciousness of the viewing subject: what hooks refers to as the importance of ‘the location from which we look’ and the ‘political choices’ informing that looking (see ‘Viral Landscapes’, AM409).

Rose’s recent question has not only a pressing urgency but also a long history of struggle in feminist art practices and debates since at least the late 1960s. The viciousness of sexual harassment in public and private spheres is inseparable from a political culture characterised by control over how definitions of pleasure and violation are and have been decided. An example is Rush Limbaugh, a US right-wing talk show host with a weekly audience of some 14 million. His radio broadcast response (6 May 2004) to the horrific images of US military abuse and torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib was to declare that it was a ‘brilliant manoeuvre’ to cause cultural and sexual humiliation to male Iraqis by forcing them to disrobe in front of one another, be photographed in front of a woman and then spread the images around the Arab world: ‘We have these pictures of homoeroticism that look like standard good-old American pornography, the Britney Spears or Madonna concerts or whatever.’ The day before, he moaned that ‘American culture is being feminised’ and that the outraged reaction by ‘the Libs’ (anyone on the left) to ‘the stupid torture is an example of the feminisation of this country’.

In Limbaugh’s constant self-pitying complaints about the effects of liberals and feminists in the US, he exemplifies the pathetic male. To paraphrase Johnson, it is in this male two-step – the abuse/torture apologist plus the manipulative sufferer of a culture ‘being feminised’, in both guises seeing himself as powerless – that patriarchal power lies. This is the oppressive culture in which feminist practices informed by writers such as Butler, hooks, Johnson, Rose and Vance have to ‘become’ by being mischievous, subversive, perverse and ‘leaving open the question of what sexuality at its wildest – most harmful and most exhilarating, sometimes both together – might be’.

Francis Frascina is an art historian and writer.

First published in Art Monthly 416: May 2018.