Michael O’Pray Writing Prize

Together, Alone: Watching Sandra Lahire in Lockdown

Rachel Pronger discovers in earlier experimental films a familiar tension between the social being and the individual body

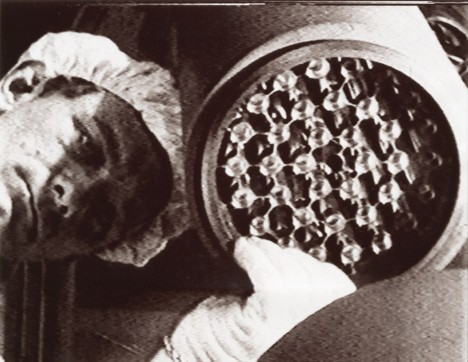

Sandra Lahire, Plutonium Blonde, 1987

In March 2020, the early days of the UK lockdown, it was difficult not to view everything through the filter of Covid-19. Films of actors talking, dancing and laughing began to feel anachronistic, dispatches from another world. Just as Hollywood directors found ways around the postwar Hays Code regulations, using the subtlest of gestures, so in lockdown images of touching, embracing and kissing became invested with new subversive weight.

In this context of fevered deprivation I began watching the films of Sandra Lahire. On furlough, and facing an indefinite stretch of empty days, I was eager for distraction. The discovery of a trove of Lahire’s films (then streaming via BFI Player) seemed to offer an escape. A British artist active from the 1980s until her death in 2001, Lahire is separated from the pandemic by two full decades. Yet as I watched, the resonances between Lahire’s ‘then’ and our ‘now’ became disquietingly apparent. The specifics differ, but her preoccupations, now pandemic cliches – bodies, science, alienation and connection – uncannily capture the lockdown mindset. In her films our ‘unprecedented’ moment was reflected paradoxically back to me as the years separating us collapsed.

At the heart of Lahire’s work lies a timely contradiction: the tension between ‘togetherness’ and ‘aloneness’. As part of the feminist workshop movement, Lahire’s practice was forged in an environment of collectivised making. Studying with Tina Keane and Malcolm Le Grice in her 20s at Saint Martin’s School of Art, alongside Sarah Turner and Isaac Julien, she encountered the experimental London Filmmakers’ Co-op, finding a home with peers such as Alia Syed, Sarah Pucill and Lis Rhodes.

In Margaret Thatcher’s atomised Britain, living and working collectively was a pointedly political gesture. Lahire became a central figure within a group whose lives intertwined professionally and personally: she composed scores for Rhodes, she cast Turner, she wrote about the work of her partner Pucill. Yet, although produced within a collaborative environment, Lahire’s films have an undeniable individuality. Themes of isolation and detachment from community and society, and even from one’s body, recur, while autobiographical fragments – diaries, monologues, letters – construct an intense interiority.

This distinctive voice can be traced back to Lahire’s first film, Arrows, 1984, a candid account of anorexia defined by its collage of layered images, sound and narration. In the opening moments, jagged strings squeal over images of caged birds as well as Lahire’s body, which spins before us, ribs starkly visible. In a voice-over, Lahire describes being trapped in a malfunctioning body: ‘I am so aware of my body, but it hurts … all alone, in this big empty skin.’ Here, Lahire plays with self-portraiture, appearing before us first clothed, then naked, apparently the powerless subject of the camera’s gaze. Then the perspective is flipped. Lahire appears again, but this time she holds the camera: both subject and bearer of her own gaze.

Arrows centres on the solitary figure of the artist, but Lahire is not alone. The credits offer a list of collaborators and locations, such as Saint Martin’s, a women’s therapy centre and ‘the women who replied to a letter about anorexia in Feminist Art News’. Arrows was not made in isolation, yet it presciently captures the claustrophobia of lockdown. This dispatch from Lahire’s ‘big empty skin’ is a portrait of alienated selfhood that resonates powerfully with those whose experience of the pandemic has been of confinement. Like Lahire, we began turning our gaze onto ourselves – via selfie, webcam, journal – in search of connection in a locked-down world.

Lahire’s universe is populated by women living cut off from society, deprived of the contact that might liberate them. As a filmmaker emerging from a collectivised movement, Lahire always sought to connect the individual to something larger. Her lone women are also emblematic figures, representatives of a greater shared experience. Arrows sets this template, offering us both Lahire as herself (the artist in self-portrait) and Lahire as symbol (the universal anti-heroine). This connection is signalled from the self-shot photography of the opening scenes to the animated silhouette of a woman consumed by snakes, stylistically reminiscent of a cave painting or Greek vase. Aligning herself with a long history of female suffering, Lahire reaches backwards in time, collapsing myths: the young woman in 1980s London becomes Eve, the ultimate symbol of wronged womanhood.

Ten years after Arrows, Lahire would look to another, more contemporary symbol of feminist struggle. Living on Air is a trilogy of films dedicated to Sylvia Plath. The iconic writer was a lifelong obsession of Lahire’s, Plath’s poetry featuring regularly in her work (Lahire was also working on a PhD about Plath at the time of her death). For Lahire, this trilogy was an act of resurrection. In the first film, Lady Lazarus, 1991, almost every word comes from archival recordings. The title card announces ‘a film spoken by Sylvia Plath’, as if it is channelled rather than directed. The writer comments on the action and even shapes the aesthetic. When we hear, for instance, Plath describe poetry as a ‘tyrannical discipline … you’ve got to burn away all the peripherals’, Lahire’s charred landscapes cohere as its filmic equivalent, reducing colour to a pink-tinted monochrome. Single images, such as a candle burning or a bell ringing, are stripped of context, becoming symbols rather than objects. The world is boiled down to its elements.

Although Lady Lazarus is built around her, Plath is not the film’s heroine. Our protagonist is an unnamed woman, played by the artist Sarah Turner. We watch Turner attempt to conjure spirits with a Ouija board, and follow her on a road trip-like pilgrimage across the US, visiting cemeteries, hospitals and diners. Plath is a ghostly presence, always audible but never truly present. Turner walks and drives alone. The two women never meet. Lady Lazarus is about an inability to connect, a woman pursuing a ghost.

A comparable image is found in Plutonium Blonde, 1987, where two women are bound together but forced apart. Part of Lahire’s trilogy of anti-nuclear films, Plutonium Blonde is about the destructive potential of science. A female worker (the titular blonde) sits inside a power-plant terminal, her inscrutable expression illuminated by banks of screens. Beyond the wire fence of the plant, another woman (played by Lahire), walks through verdant fields, the sun behind her. Fragments of archive and news footage are edited into the parallel narratives of the two women, as both remain silent and separate, secured in sealed worlds, specimens beneath glass.

Plutonium Blonde’s distrust of the scientific establishment draws out another theme that speaks to a pandemic-stricken era. Science is often viewed suspiciously in Lahire’s films, specifically male scientists who wield medicine to control misbehaving female bodies. In Arrows, Lahire discusses plastic surgeries, describing a grim intervention in which the surgeon ‘literally dissolves fat and aspirates it with a suction tube’. In Lady Lazarus, such brutal attention is applied to the control of female minds. Given Plath’s legend, the viewer clearly understands the significance of footage of deserted psychiatric wards with signs that directs us towards ‘Lobotomy’ and ‘Electrotherapy’ rooms.

In Plutonium Blonde, a woman is implicated in similarly destructive scientific activity. It is unclear whether the blonde is malevolent or benign, a willing participant, a cog or a rebel. As a male voice-over authoritatively extols the safety of nuclear power, the blonde remains sat behind a bank of computer screens, her expression unreadable. Occasional flashes of a rebellious outside world are glimpsed, suggestive of her mind searching for mental liberation when physical escape is impossible. Even more than Arrows or Lady Lazarus, Plutonium Blonde teases out the grey area between ‘togetherness’ and ‘aloneness’.

In lockdown, we keenly feel the disconnect between our hermetic interior lives and the hyperconnected thrum of social media. Just as the blonde’s bank of computers enables her to channel power beyond herself, so science allows us to achieve a superhuman level of connection – to roam the world without leaving our homes. Yet, as the blonde discovers, this technology only goes so far. Just as she longs for life beyond her lab, we too long for contact beyond a two-dimensional image, to reach past the webcam and get under the skin.

While her work is full of dark extremes, watching Lahire in lockdown did not leave me feeling bleak. Her work evokes isolation so vividly because she is deeply invested in its alternative, and her ability to capture sensual possibility means that the work offers hope: the triumphant vision of a woman bearing a camera, the strident voice of a genius poet, a glimpse of nature behind barbed wire. Two decades after her death, I found in Lahire’s films unexpected succour. Watching Lahire, in the most uncertain of times, I felt a hand reach out across the span of dead time, one lone woman to another. A kind of connection in a disconnected moment. Alone, but somehow strangely still together.

Rachel Pronger is a runner-up in the Film and Video Umbrella and Art Monthly Michael O’Pray Prize 2020.

The Michael O’Pray Prize is a Film and Video Umbrella initiative in partnership with Art Monthly, supported by University of East London and Arts Council England.

2020 Selection Panel

- Terry Bailey, senior lecturer, programme leader, Creative and Professional Writing, University of East London

- Steven Bode, director, FVU

- Chris McCormack, associate editor, Art Monthly

- Rianna Jade Parker, critic, curator and researcher

- Heather Phillipson, artist and poet