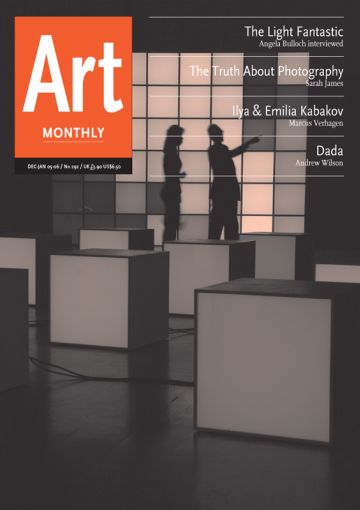

Feature

The Truth About Photography

Sarah James argues that it is time to re-examine some fundamental issues

Photographic art practices have continued to proliferate in the last decade, yet we have not witnessed an analogously rich growth in photographic theory. No new paradigm of thinking about photography has emerged. Past theoretical truisms have little significance in today’s context, but continue to erode those characteristics that were once so fundamental to the medium, such as agency, history and meaning. Photography has long been accepted into the canon of art, legitmised by a substantial body of poststructuralist theories. However, in today’s art world defined for some by relational aesthetics, and a biennale art of social participation, process, collaboration and installation, photography occupies a privileged autonomous place within both museum and market like that enjoyed by artworks that were once the subject of photography’s critique.

Several issues must be addressed in any elaboration of contemporary photographic art practices: the complete lack of any significant development in photographic theory in the last decade; the continued analysis of the medium in ‘out-moded’ semiotic or ideological terms; the need to focus upon the implications of postmodern theories upon photography, instead of understanding photography to be a symptom of Postmodernism; the institutional politics surrounding photography in the present art world, and the unsatisfactorily analysed position held by documentary photography and the documentary aesthetic. Such a focus crucially reopens a consideration of the materialist and dialectical qualities of the medium, which will entail a necessary exploration of long neglected categories such as truth, history and agency. In light of recent discussions of modernity, and in contrast to the hegemonic art historical reading of the photograph as a symptom of the postmodern, photography is the medium which is best placed to open up entire new discussions of the situation in art after Postmodernism.

Discussions surrounding photography in the 70s were dominated by semiotics and structuralism, as conceptualist practices cast photography as document, index, trace, and it became the best medium for unmasking modernist myths. Photographic art was necessarily a deconstructive art, with its now clichéd celebrated exemplars such as Sherrie Levine, Louise Lawler, Sylvia Kolbowski, Barbara Kruger or Richard Prince. Equally, the growing influence of ideological critiques and Foucauldian thought, propagated in Britain by theorists such as Victor Burgin and John Tagg, subjugated the medium and its analyses, revealing the camera’s gaze and celebrating the dissolution of the author, universality and originality. By the early 80s, with the marriage between Baudrillardian new media theories and the practice of photographic appropriation, the medium was considered to be entirely symptomatic of Postmodernism, as diagnosed by a long list of influential voices including Rosalind Krauss, Douglas Crimp, Martha Rosler, Abigail Solomon-Godeau or Andy Grundberg. In addition, because of the hegemony of postmodern photographic theories, photography – paradoxically, a medium so intrinsically attached to the real – had become utterly entrapped in that deconstructionist destruction of the relation between representation and reality. Furthermore, the development of photographic art since the 60s had become inseparable from its function as social and political theory in practice. Simultaneously the medium was theoretically caught up in both a delayed Modernism (in the early 70s, the acceptance of photography as art seemed tied to a vision of it as conforming to a Modernism that had long been moribund in other arts) and a radical critique of that Modernism. This situation played a crucial role in the rise of postmodern art practices, while at the same time being the medium subjected to the worst violence of postmodernist theorising.

The theoretical debates staged since the late 80s surrounding the legitimacy of Postmodernism and its relationship to Modernism are echoed – albeit in the main with much more problematic over-generalisations and shoddy conclusions – in photographic theory. That photographic art became problematically entangled with Postmodernism is hardly a new observation; it has been interrogated, following Terry Eagleton’s broader critique, from different positions by Grundberg and more convincingly by Steve Edwards. The latter attacked the postmodernising of photography which ultimately allowed for no reading of it outside of representation, and therefore allowed for no reality or meaning. For Grundberg, who viewed Postmodernism not as break with Modernism but as evolving from it, photography as a medium has an inherently postmodern strain. In fact he saw the seeds of a postmodernist attitude in the work of Walker Evans (his 30s images of billboard and signs), Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander. The problem here though is that such a view sets up a dichotomy between those values associated with Modernism – the aesthetic, its autonomy and medium-specificity – and photography in contemporary art, which was understood as resistant to formal or aesthetic analysis.

It is equally striking that the typical narratives of modernist and postmodernist photography are limited to an Anglo-American reading. As Edwards argued, looking to Berlin and Moscow, other neglected Modernisms (not only the Greenbergian one) suggest very different photographic developments, such as the dialectic of surface and facture, which scrutinises representation without losing grip on the real. Equally, in relation to Postmodernism, the photographic practices of the former Eastern Bloc since the 70s offer a way of disrupting a problematically homogeneous Postmodernism. For example, the photographic art of the former GDR is often characterised in terms of its distinctive dialectical representations of agency. Further, there was a common trope of photographs which pictured pictures within pictures, such as Evelyn Richter’s series of exhibition visitor photographs of the 70s, where gallery visitors are shown in front of infamous paintings of the time, and a dialogue was initiated and complicated between the anonymous photographic portrait, and the painted portrait, the photographer and the subject. Equally, it was a common mode of critique to incorporate worn and tired poster images of Lenin or Walter Ulbricht provocatively in the background of photographs. Such photographic ‘pictures within pictures’ suggest alternative, yet crucial models to the American Postmodernism of Levine’s representations. Indeed, the dialectical politics of formalism and historicism that underpin artistic practices from the 60s onwards can be seen, as critics such as Benjamin Buchloh have suggested, as having profoundly different resonances in the USA and Europe.

Apart from the flood of largely insubstantial theories of ‘post-photography’ throughout the 90s, which mostly re-read Walter Benjamin or Roland Barthes in terms of the digital world, there has been a striking lack of any convincing theoretical discourse addressing the crucially changed context of photographic practices today, so that the medium still occupies a strange temporality in relation to the present. This lag is also visible in the institutional context. It is glaringly apparent that the UK still has a significant problem with the medium. Unlike Berlin, Paris and New York, there is no large photographic venue in Britain, even in the capital. Although The Photographers’ Gallery, the country’s first independent photography gallery, was established in 1971, Tate did not present its first major photography show until just two years ago with ‘Cruel and Tender’ of 2003, and that its current blockbuster this year is the painterly photographer Jeff Wall is equally telling. Obviously there were other earlier substantial exhibitions by photographic artists such as Cindy Sherman at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1991, followed by Nan Goldin and by Philip-Lorca diCorcia in 2003. The same year saw Sherman at the Serpentine Gallery, and last year, the Hayward’s Jacques-Henri Lartigue show was accompanied by ‘About Face’ dealing with photography and the death of the portrait. While at the Barbican Art Gallery, the 2004 Tina Modotti and Edward Weston exhibition has been followed by those of Tina Barney and Araki. And the V&A, an institution traditionally attached to the medium, is currently showing a Diane Arbus exhibition, and last year showed Bill Brandt. Such a catalogue of exhibitions serves to demonstrate the imbalance and incongruities in the institutional canon of photographic art and its incorporation of both successful straight Modernism and celebrated Postmodernism.

In the present internationalist, post-medium, post-Bourriaud climate, the photograph can be seen as becoming more and more the singular object of art that painting once was. But, crucially, this is taking place in an entirely different historical and cultural moment to the conservative legitimation of pictorial photography, or Peter Galassi’s Szarkowskian efforts to relate the medium to painting in the 80s. Yet, there is some echo – albeit in the guise of contemporary concepts – of Edward Steichen’s reduction of photography to illustration at the MoMA of the 50s, whereby the museum emerges as the main orchestrator of meaning. This is especially so in the context of the rise of superstar curators such as Hans Ulrich Obrist and exhibitions like ‘Translation’ held recently at the Palais de Tokyo and conceived in collaboration with French artists M/M. This time around photography decorates galleries and transforms institutional spaces, like style magazine wallpaper. The photograph can no longer just be pitched qua Benjamin against the mass media, even in post-photographic digital terminology. It must instead be understood against the array of installation and collaborative practices within the context of the art world. Photography’s conceptual position is much less easily defined than it was in the 70s (as document to performative, conceptual, or land art practices). It is in the midst of such inter-relational, yet arguably highly co-opted global artistic practices and the various postmodern or multiculturalist narratives that legitimise them, that the position of documentary photographic art becomes particularly significant, as it is here that questions of truth and agency are most poignantly located.

To reject the hegemony of photographic theories based on ideology critiques is not to dismiss the question of ideology, or the fact that all art has a political or ideological existence. In the same way, to suggest moving on to a ‘post-theoretical’ position, is not to deny the invaluable revelations, disruptions and politicisations made by theoretical onslaughts since the 70s. However, in the 80s Edwards correctly questioned the theoretical dissolution of the subject and values such as truth involved in the postmodern positioning of photography. Indeed, as Rosler had earlier prophesied in 1979, a belief in the truth-value of photography was to become ever more explicitly assigned to the uncultured, the naïve, and the philistine. Both stressed the need to look at countervailing tendencies within photography, particularly documentary, which obviously becomes central in debates over transparency of discourse, the problem of ‘how to get the outside to look in’, and the question of maintaining a strong subject position. The dialectic between formalism and historicism, and the difference between American and European variations is perhaps most apparent in documentary photography. In America, as Rosler has stressed, documentary has been much more comfortable in the company of moralism than wedded to a rhetoric or programme of revolutionary politics, as is the well entrenched paradigm in which a documentary image has two moments: the immediate, instrumental one, in which an image is caught or created and held up as testimony, and the conventional ‘aesthetic-historical’ moment, that is less easily defined in its boundaries.

In the last decade, the continued emergence of documentary practices has been coloured by the success of snapshot, confessional or more technically proficient documentary, such as the work of Nan Goldin, Martin Parr, Wolfgang Tillmans or Richard Billingham, that often sits close to fashion and style magazine images. One of the few exhibitions that directly addressed the issue of contemporary documentary was the V&A’s ‘Stepping In & Out’ of 2003, and here the rather vague suggestion was simply that contemporary documentary, although not defunct, could not either be considered as a unified form. Yet within other strains of documentary practice values opposing the postmodern can be located in a photography that is critical of some modernist values and within which categories such as aesthetics and agency are crucially altered. Anti-postmodern values such as a fidelity to the medium and the subject and high technical accuracy can obviously be seen in many prominent strains of documentary, as for example in Paul Graham’s photographs of DHSS waiting rooms from the 80s or Rineke Dijkstra’s more recent portraits of bullfighters and teenagers. Equally, of great importance to many of these documentary practices is the dialectic between the particular and universal. Indeed, a defining element of the documentary image is its particularity, that it represents a specific moment. But this ability to evoke identification equally means a loss of specificity in its universalisation.

Even values associated with past photographic conceptualisms can be re-read. Seriality can be understood in terms of difference as opposed to sameness, and photographic projects can be seen in terms of longevity as opposed to the instantaneous in, for example, Roni Horn’s You Are the Weather, 1994-95, part of a series made in Iceland over 25 years comprising a set of straight portraits of a friend. Equally, the temporality of the medium can be pictured in terms of its slowness, as opposed to its snapshot capabilities, as in Hiroshi Sugimoto’s series of movie theatres and drive-ins from the 90s, for which the exposure corresponds to the length of a movie screening so that the cinematic images cancel each other out to leave a blank minimal white rectangle and absent audience. The relationship between the pictorial and reportage within documentary can also be re-examined, as in Graham’s ‘Troubled Land’ series from the 80s, which juxtaposes an idyllic landscape with signs of violence in Northern Ireland. Further, the materiality of the photograph can be re-emphasised, as is apparent in many recent, almost romantic returns that explore the objecthood of the photograph in opposition to Krauss’s post-medium condition, for which Anna Barriball’s series of untitled found photographs overlaid with ink and bubble mixture provide just one example.

The specific aesthetics of documentary photography lie in the fact that the language of aesthetics is always available to rescue documentary from itself, that is, from its own truth claims. This trope Rosler asserts, far from being born of postmodern doubt, was typical of Modernism: the insertion of unstated commentary between the sheer sensation of the image and its reception. Within documentary aestheticisation and universalisation therefore do not need to be exclusively considered as negative, because accessible aesthetic forms convey meaning, subjectivities and politics. Today, modernist explications of self-referentiality make slippery crossovers into the postmodern, and the autonomy of a work of art becomes a manifestation of individual human freedom, which tries to resist absolute commodification. The dual issues of art’s instrumentality and of its truth are especially naked in respect to photography. However, as Peter Osborne has remarked in relation to Theodor Adorno and the situation of art after Postmodernism, the fact that the course of history has shattered the basis on which speculative metaphysical thought could be reconciled with experience, does not abolish the problem of truth.

On the contrary, and vitally, it forces materialism upon metaphysics and, crucially, this is exactly the case within documentary photographic practices.

Sarah James is an art writer.

First published in Art Monthly 292: Dec-Jan 05-06.