Review

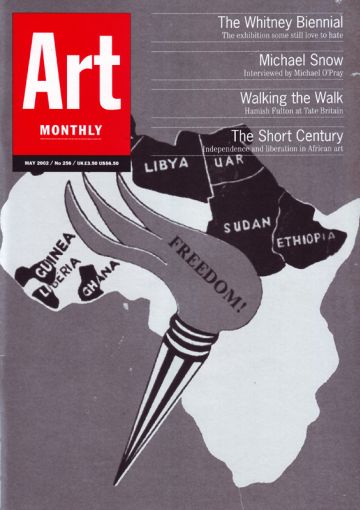

The Short Century

Barbara Pollack finds at PS1/MoMA a new model of exhibition that reveals Africa’s influence on western modernism

Until the 2nd Johannesburg Biennial in 1997, Africa was comfortably ignored as a source of contemporary art. That exhibition, for all its administrative and aesthetic problems, irrevocably altered western viewers’ perception of the presumably global art world, not only by launching the careers of a long list of African artists, but by encouraging collectors and curators to visit South Africa and witness the creativity of cultural upheaval. Its curator, Nigerian-born Okwui Enwezor, was already sky rocketing to international prominence. He will soon unveil his latest achievement as artistic director of Documenta XI. Even so, it is hard to imagine how he can top the accomplishment of his groundbreaking exhibition, ‘The Short Century’, which opened at the Villa Stuck in Munich in February 2001 and now ends its tour at PS1/MoMA in New York City.

‘The Short Century’ covers the emergence of independent nations throughout the continent of Africa from the ‘beginning of the end’ of colonialism in 1945 through to the election of Nelson Mandela as President of South Africa in 1994. Organised with a team of international curators, the exhibition openly examines the often contradictory responses to liberation as reflected in a vast variety of cultural phenomena – textiles, visual art, photography, graphic design, film, music, architecture, and literature. By allowing this complexity to speak for itself, ‘The Short Century’ avoids the didacticism of most history exhibitions and, in so doing, establishes a new paradigm for a survey show of non-western art. In fact, the exhibition astutely holds a mirror up to the subtle racism of the Guggenheim-style approach to globalism, ie start with tribal artefacts and end with an installation by a token contemporary art star. Resisting this model of a unified narrative (which only reduces complex cultures to one-dimensional stereotypes), Enwezor instead offers Africa cultural parity with European and American modern art movements by allowing it the same degree of multiplicity and the right to its own internal contradictions.

Colonialism imposed the idea that Africans were a people without culture, in need of ‘civilising’ influences. But independence did not immediately eradicate this pernicious myth, as western media representations from the period aptly demonstrate. A 1953 issue of Life Magazine with the headline, ‘Africa: A Continent in Ferment’, used a picture of a ‘native’ tribesm an as its cover illustration. BBC newsreels of the independence ceremonies, with Queen Elizabeth or King Leopold arriving to shake hands with their former colonial subjects in Kenya, Congo, Zambia, Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal, illustrate the degree to which the very process of liberation was often controlled and orchestrated by the colonial powers. And, even after 1960, when 17 African countries achieved independence, intellectuals and artists in the continent were left with the sticky problem of how to form a post-colonial identity while maintaining full participation in the modern (aka European) world.

African identity is a primary theme throughout the exhibition,starting with a brief exploration of those movements from the 30s, such as Pan-Africanism and Negritude, which resisted western influences as a means of establishing an independent aesthetic untainted by the colonial experience. At the same time, numerous artists embraced abstraction and modernist tendencies, adapting these techniques to African themes. Picasso’s appropriation of African tribal totems may have been a turning point in European Modernism, but artworks by Gerard Sekoto, Ben Enwonwu, Thomas Mukarobgwa and Ernest Mancoba (a founder of the CoBRA movement) on view illustrate the extent to which Modernism flowed both ways. These artworks are strangely serene in comparison to the violence and political upheavals of the decolonisation process, copiously documented in the surrounding galleries with pictures from Drum, Paris Match, Magnum, the Nigerian Morning Post, and other publications. The fact that the promise of liberation did not always achieve a happy ending is illustrated in a separate gallery devoted to the Congo; a series of paintings by a commercial artist, Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, tells the story of the rise and fall of liberation leader Patrice Lumumba, while Raoul Peck’s film biography plays on a television monitor.

Most of this period is far too little known in the United States, where African history is taught in schools only as tangentially related to the history of slavery. Meanwhile, American art museums have only complicated this rampant ignorance by relegating African art to separate wings devoted to tribal artefacts. While these museum curators have worked long and hard to educate American audiences about the glories of traditional African iconography, the overall impression derived from this limited exposure is that Africa never underwent a modernist period, that modernisation itself is beyond the grasp of African nations.

Because of this intellectual vacuum, many of the contemporary art projects arriving in New York in the late 90s from South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and a variety of other African urban centres have been interpreted and misinterpreted as merely the result of international biennials (as if Artforum secretly infiltrated these diverse places and converted hordes of non-western artists). ‘The Short Century’ repositions these works within a much more specific context, one that encompasses these countries’ own self-conscious modern practices and political legacies. For example, Zwelethu Mthethwa’s portraits of inhabitants in South African townships can now be seen as a direct outgrowth from the studio work of Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe. Yinka Shonibare’s use of faux African fabrics is not merely a postmodern shortcut, but recalls the central role of textiles and design patterns in political posters and protest movements. Even the pathos-filled animations of William Kentridge can be linked to theatre productions of Athol Fugard as well as the drawings of Dumile Feni, a South African artist from the 50s and 60s and the woodcuts of Georgina Beier, who moved to Nigeria from Great Britain in the late 50s.

Just as ‘The Short Century’ makes these connections in ways that feel serendipitous, the installation of contemporary artworks also encourages dialogue. South Africa is extremely well presented in one gallery that places Kay Hassan’s multimedia installation Flight, 1995/2001, across from Antonio Ole’s Margem da Zona Limite: Township Wall, 1994/2002, a monumental interpretation of a township streetscape with Sue Williamson’s For Thirty Years Next to His Heart, 1990, a series of laser prints made from the pages of a black South African’s identity passbook, hanging on an adjacent wall. Juxtaposition is not merely a curatorial strategy, but the primary means by which many contemporary African artists can address the contradictions of identity in post-colonial society. Georges Adeagbo’s room-sized installation, Le Socialisme Africain, 2002, filled with magazine covers, elementary school textbooks, record albums and antedated maps, adds up to an encapsulated version of popular culture’s representations of and impact on his native Benin.

In 1955, Edward Steichen curated the blockbuster exhibition ‘The Family of Man’, at the Museum of Modern Art. With over 500 photographs covering family life around the globe, the enterprise rested on a belief in international Modernism, that photography (even when the photographs were taken primarily by American and European photographers) could unite the world. Postmodernism, as well as the continuous political conflicts of the last five decades, have demonstrated the limits of that proposition, but whilst art museums have learned a new term, ‘globalism’, they have yet to devise a model to replace good old-fashioned internationalism; ‘The Short Century’ may very well turn out be that model. If it does, it will certainly prove Enwezor’s theory that Africa is as fundamental to the advancement of western culture as the West presumes itself to be to Africa’s development.

‘The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994’ was at PS1/MoMA, New York, 10 February to 5 May 2002.

Barbara Pollack is an artist and writer living in New York.

First published in Art Monthly 256: May 2002.