Feature

The Main Complaint

Psychosexual fixations and neuroses do not respect national or racial boundaries says Eddie Chambers

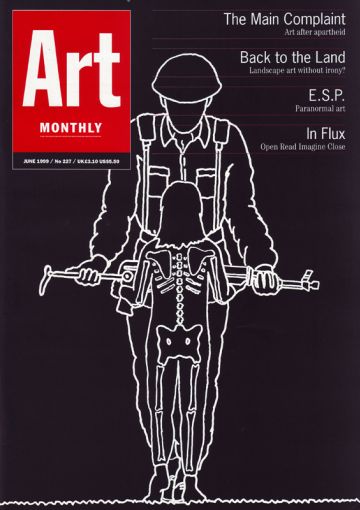

William Kentridge, History of the Main Complaint (title page), 1996

William Kentridge has established himself as one of the weightiest players within South African contemporary art. Time and time again, all sorts of curators have found themselves drawn to and engaging with Kentridge’s work. In this country his work has been included in two of the three major group exhibitions of South African art that have taken place during this decade.

Kentridge’s work was featured in ‘Art From South Africa’ at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, back in 1990. Five years later, Kentridge was one of the ten artists whose work made up the ‘Transitions’ exhibition at the Hotbath Gallery, Bath, and Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast. Kentridge has also been busy on the home front: his work was included in both Johannesburg Biennials - 1995 and 1997.

Despite having long become a darling of the biennale/mega-exhibition circuit and the South African group show, the current Serpentine exhibition is the first opportunity that gallery-going audiences within reach of London have had to see a substantial body of his work. The exhibition consists of two parts: there are the wall-based drawings and other works on paper, such as etchings, and there are the animated films. Much of the gallery space has been given over to the latter, with no fewer than three separate areas in which are projected a number of films made by the artist over a ten-year period.

Kentridge is a talented and able draughtsman, and he has developed a fascinating process of making animated films by working and reworking wall-based charcoal drawings. But interesting though Kentridge’s work is, the most significant debates it raises relate to questions of how and why as a South African artist he has managed to achieve the celebrated status he enjoys. Kentridge’s success as an artist, particularly beyond South Africa, throws up disturbing reminders of the ways in which issues of racial hierarchies and their attendant cultural and political orthodoxies have taken a seemingly irreversible hold on the world during the course of this century.

Make no mistake, in international curatorial circles, Kentridge has come to represent, officially or otherwise, South Africa. Or, more accurately, he represents those elements of South Africa of which we approve. When David Elliott curated ‘Art From South Africa’, white artists like Kentridge were presented to us as representing liberal South Africa’s considered and serious resistance to apartheid and a concurrent willingness to engage artistically with the realities of that country’s odious and self-destructive programme of ‘separate development’. Witness Kentridge in the ‘Art From South Africa’ catalogue: ‘I have never tried to make illustrations of apartheid, but the drawings are certainly spawned by and feed off the brutalised society left in its wake. I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings. An art [and a politics] in which my optimism is kept in check and my nihilism at bay.’

That was then. This is now. Now, with apartheid, formally and officially at least, a thing of the past, Kentridge’s projected self-image has shifted slightly, but significantly. He is now taken to represent the new supposedly non-racial, liberal, non-hierarchical South Africa. His work is taken to represent not only the cathartic process of post-apartheid healing, but also the image of South Africa as a forward-looking country, wholly in step with Western liberal values and aesthetics.

What is significant about the evolution of Kentridge’s profile as an artist over the course of this decade, is that it is he, a white male (artist), who has been selected by an international coterie of curators to represent intelligent, considered and acceptably dispassionate resistance to apartheid. This self-image then evolved into one in which Kentridge, again as a white male (artist), is embraced and curatorially celebrated as representing the new South Africa.

The evolution of Kentridge’s profile points to not much other than racial business as usual. Of the South African population of about 38 million, some 29 million are black, roughly five million are white, three million are so-called ‘coloured/mixed race’ and approximately one million are of Indian descent. Yet no black South African artist has any sort of proflle that comes even close to that of Kentridge. The same must be said of South Africa’s so-called ‘coloured’ artists. Such is the emphatic eclipsing by white South African artists of all other ethnic groupings that, as well informed as we might consider ourselves to be, most of us would be hard pushed to name even one South African artist of Indian origin who has made it successfully into the international exhibiting arena. In other words, the 29 million majority, along with South Africa’s ‘coloured’ and Indian populations have found themselves being represented, in the art galleries of the world, by a small impregnable clique of white, primarily male South African artists, of which William Kentridge is the prime example.

This scenario is wholly consistent with the racial hierarchies and their attendant ideologies that have, during the course of this century, established themselves the world over. Presumably, in showing the Kentridge exhibition, the Serpentine is seeking to embrace and acknowledge South Africa as a new member of the international (artistic) community. But it has chosen to do so by ignoring those people and artists who much more readily qualify as credible (artistic) representatives of South Africa’s struggle to heal and rebuild itself.

Kentridge’s biographical details attest to the ease with which white males such as he can choose their career options, choose their higher education, choose to live in South Africa and choose to travel beyond it. For example, Kentridge studied Politics and African Studies at the University of Witwatersrand in the early–mid 1970s when it was essentially a ‘white’ university. He was then a student and a teacher at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. From teaching etching, Kentridge then studied mime and theatre in Paris. And so it goes on. Filmmaking, theatre, puppetry, opera, acting, writing, directing. Meanwhile, most black South Africans, finding themselves with virtually no life choices or career options, continue to live in poverty. And so it is that the curators of the world readily, happily, embrace one of South Africa’s most privileged minority as one whose ‘work raises powerful issues that bear on the human condition in general - victimisation and suffering, guilt and confession, domination and emancipation’.

Unless you include the damage of repetitive strain injury brought on by endless liberal hand wringing, people like Kentridge - artists like Kentridge - have not done badly out of South Africa and are the clear beneficiaries of whatever that country was and now is, both under its previous condition and its new, so-called post-apartheid condition. Kentridge’s technical skills, in drawing, in etching, in animation and in filmmaking are beyond doubt. What is doubtful is the extent to which his work can honestly be said effectively to engage or connect with the viewer. He occupies much the same space as that taken, elsewhere in the world, by artists such as Alfredo Jaar. Such artists are happy, anxious even, to present themselves as acknowledging the political conditions of the wretched of the earth, whilst critiquing the antics of their tormentors. Yet these same artists are reluctant to acknowledge, in any way, the bountiful privileges of their social, racial and economic status. After all, Kentridge’s work continues the well-established tradition in which white South African artists are able to produce lavish, expensive, expansive work, while their black counterparts are able only to produce more modest works.

And yet, within Kentridge’s work, there are interesting flashes of tension and inspired creativity. Take for example the animation Johannesburg - 2nd Greatest City after Paris in which the artist developed a fascinating technique. To quote him directly: ‘The film was made in my studio; a drawing on the wall at one end and a wind up bolex camera at the other. I would draw, walk across the room, shoot off two frames of fllm, walk back to the drawing, so at the end of the film I was left with about 20 rather beaten drawings.’ The film chronicles the battle between two characters, Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitlebaum, for the hearts and ‘mines’ of Johannesburg and the affections of Eckstein’s wife. In this film, the image of Soho Eckstein, a property magnate who buys up half of Johannesburg, resonates with a raft of stereotypes that could be read as bordering on the anti-Semitic. Eckstein is presented as a bloated, avaricious and exploitative figure.

The Serpentine press release informs us that the character of Eckstein is in actuality based on the artist’s grandfather and that Teitlebaum, who always appears naked, is modelled on Kentridge himself. Thus, what at first sight appears to be a dark, brooding, menacing series of animations exploring South Africa’s body politic, turns out to have some sort of grand autobiographical narrative or reading. Work that examines political issues by locating actual or fictitious elements of an artist’s personal life at its core is one thing, but viewing this work we realise that Kentridge has a generous supply of psychosexual fixations and neuroses that demand a space and place alongside examinations of apartheid.

But while psychosexual fixations and neuroses do not respect national or racial boundaries, it is unlikely in the extreme that a black South African artist, given access to such a wonderful gallery space, would have filled it with such introspective meanderings. Nor would the Serpentine have allowed them to.

‘William Kentridge’ was at Serpentine Gallery, London 21 April to 30 May 1999.

Eddie Chambers is a Bristol-based curator.

First published in Art Monthly 227: June 1999.