Feature

The Killing Machine

Barbara Pollack traces the legacies of David Wojnarowicz in New York today

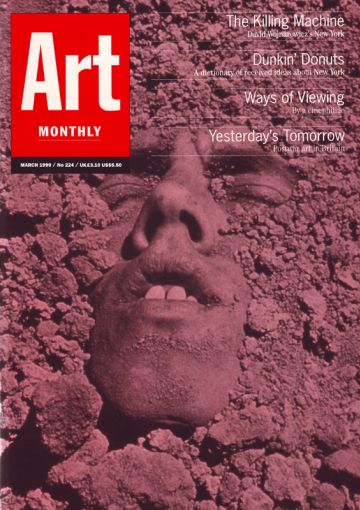

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled, 1993

‘I wake up every morning in this killing machine called America and I’m carrying this rage like a blood filled egg and there’s a thin line between the inside and the outside a thin line between thought and action and that line is simply made up of blood and muscle and bone.’ – David Wojnarowicz reading for the Needle Exchange shortly before his death in 1992.

When David Wojnarowicz’s body finally gave out in 1992, hundreds packed his funeral at St Marks Church to pay respects to a spirit that never gave in. Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS at the age of 37, left behind a legacy of paintings, photographs, sculptures, videos, recordings and writings that were produced in barely over a decade - emblematic of an artist who always ran his life as if he was on borrowed time.

A fixture in the East Village since the 1970s, Wojnarowicz’s career rose just at the moment when the AIDS crisis began, a ‘coincidence’ that he took to heart and it became the defining premise of his identity as an artist. His first appearance in the Whitney Biennial in 1985 coincided with early reports of GRID in Newsweek, when the disease was believed to affect only homosexuals. Two years later his lover and mentor, photographer Peter Hujar, died of (and Wojnarowicz was diagnosed with) what was finally recognised as AIDS. But, even without the plague, Wojnarowicz viewed queerness as central, unhideable, undeniable, as big as the Grand Canyon, as unpreventable as an earthquake in Los Angeles.

This year, Wojnarowicz is being canonised by the New York art world with a full-scale museum retrospective and exhibitions at three other galleries - Gracie Mansion , PPOW and Adam Baumgold - while New York University, the New York Public Library and the New School have all scheduled series of symposia discussing the artist’s work. Meanwhile, excerpts from the artist’s diaries, edited by Amy Scholder, have been reissued by Grove Press.

Those unfamiliar with Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre are dazzled by the exhibitions, by his abundant output and the ostensible bravery of presenting such highly controversial work. Yet, those who knew the artist - and Wojnarowicz was the kind of person who touched many people’s lives - are appalled by the historicising and aestheticising of these posthumous presentations, and by the resulting tendency to neutralise the content. They find it equally ironic that the New Museum show is funded by Versace and that Saks Fifth Avenue has a window display in homage to the artist, remembering the Wojnarowicz who turned down an opportunity to appear in a Gap ad. ‘Brave?’ asks one long-time friend of the artist. ‘Where were all these people when he was under attack? When he was dying?’

Wojnarowicz’s history tests the accuracy of our memory of the art world of the 1980s, and challenges the official canon of art history of the period. While Julian Schnabel and David Salle were experiencing meteoric success, Wojnarowicz was painting pictures of dead cows on the side of abandoned piers by the West Side Highway, a known hang-out for male prostitutes. While Mary Boone, Larry Gagosian and Arne Glimcher snagged tables at the Odeon, an alternate universe of punk clubs, performance spaces and bodega-sized galleries cropped up in the East Village. These artists viewed themselves as permanently in opposition to the rest of America (and that included Soho and 57th Street), but created their own world. On any given night, you could go from an opening of a Wojnarowicz installation at Civilian Warfare to Karen Finley’s yam-act at the Pyramid Club, passing Jenny Holzer’s xeroxed broadsides along the street. It did not take too long for alterna-tive spaces such as Franklin Furnace and Artists Space to begin documenting this movement with group shows and catalogues. In 1985, COLAB, the loosely bound artist-collective, put together the historic Times Square show in an abandoned peep-establishment, just about the time the Whitney and uptown collectors came down and took over.

By the time Jesse Helms caught on to this dangerous cadre of artists, the East Village was over. Dealers Jay Gorney, PPOW, Pat Hearn, Massimo Audiello and many others moved to Soho, and the artists did not refuse to follow. This was widely covered at the time as the end of a movement and as a selling-out, but the change of location did not entirely erase the impetus and aesthetics of the East Village. On the contrary, it gave the new wild bunch a higher profile. While the New York Times would still like to believe that the late-80s was solely a period of neo-expressionist art stars (Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Susan Rothenberg and Fischl), an influx of artists like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jenny Holzer, as well as an endless list of others (Erica Rothenberg, Martin Wong, Jane Dickson, John Ahearn, Cristy Rupp, Ilona Granet, to name a few) brought with them a more outspoken brand of art that was explicitly political and sexual.

Wojnarowicz showed throughout this period creating full-scale installations that incorporated paintings, sculpture, photography and text. He had a personal iconography - house on fire, boy in flames, St Sebastian, Jean Genet, soldiers and cowboys - that ran through his work. But his strength as an artist is that he never did let icons disguise sexuality. Unlike Johns or Warhol, who used Americana to subsume their homosexuality, Wojnarowicz placed sexual imagery on par with American icons, insisting on an openly gay presence within the American landscape: The Newspaper as National Voodoo: A Brief History of the USA or Queer Bashing/Icarus Falling are typical titles; Fear of Evolution, a collaged canvas with the central image of a monkey carting the world around, was the artist’s way of illustrating the surrealism of the religious right; Falling Buffalo, a fairly straight-forward photograph of a natural history museum diorama of a herd falling into a canyon, became the emblematic image of the AIDS crisis.

Perhaps Wojnarowicz’s audacity came from his history. As it has often been told, he was first raised by an extremely violent father in New Jersey, then ran away at nine years of age to live with his near-criminally neglectful mother in Manhattan. By his early teens, he was trading tricks around Times Square, experiencing the conflicted power of money and attention to be gained through sex. He had no role models, no religion to rebel against, no class to live up to. He was known as a suprisingly gentle man, but his art has an anger untinged by guilt. Nor was his art a vehicle for economic mobility. This is a far cry from Robert Mapplethorpe, who traded in guilt and shame, using the marketability of the forbidden to access the wealthy. It is also quite different from an artist like Keith Haring, whose grin-winning graffitti on the subway walls of New York turned into a Haring-industry of posters, pins, baseball caps and art. Wojnarowicz’s understanding of pop culture was pure punk - offend the crowd and whoever stays is your audience. (In the 1970s he was in a band, 3 Teens Kill 4 No Motive.) Though Wojnarowicz showed and sold regularly, according to Wendy Osloff of PPOW, which represented the artist during his last years and still represents his estate, ‘he totally distrusted the art world’.

A turning point for Wojnarowicz was the exhibition, ‘Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing’, curated by Nan Goldin, at Artists Space in 1989. The show opened just after the crisis over the Mapplethorpe retrospective (which officials at the Corcoran voluntarily closed due to Congressional rumblings over loss of funding) and just before Karen Finley and the other members of the NEA4 lost their NEA grants. John Frohmayer, the head of the NEA at the time, came up to New York for the opening, which turned into a spontaneous rally for freedom of expression. Wojnarowicz’s searing essay in the show’s catalogue prompted the NEA czar to withdraw funding immediately.

Shortly after that, Wojnarowicz fought back. Excerpts from his paintings were published in a religious right newsletter (as an example of government-funded pornography) and the artist retaliated by taking the Reverend Donald Wildmon to court for copyright infringement. He won, but the court awarded him only minimal damages. His first retrospective, ‘Tongues of Flame’, travelled across the US in 1990, when only the bravest institutions would touch his work. ‘When we did the show, it was at the height of the censorship issue’, states Jeanette Ingberman, director of Exit Art (the show’s New York venue), ‘and I remember many of my colleagues being surprised that we were doing the show, asking aren’t you afraid of losing your funding?’ According to Ingberman, Exit Art could not raise a penny for his work from government or corporate sources at the time. ‘It was a combination of being really sad and really exciting’, states Osloff about handling the artist’s work during the last two years of his life, ‘because just at the time he was feeling really empowered, but he was very sick, so he was really conflicted.’

The New Museum exhibition barely takes on the important job of presenting the historic context for the work, though the work targets Wojnarowicz’s enemies quite clearly, in itself. More troubling is the installation, which turns this irrepressible output into a staid presentation categorised by medium. Suddenly, the sculptures are presented as individual objects on pedestals. The paintings and photographs displayed as separate explorations. Wojnarowicz never presented the work this way, and understood that by so doing he was defying the process that commodifies art.

Ironically, the dealers who are currently showing his work and who worked with the artist during his lifetime have found more telling ways of revealing works to a new audience: PPOW’s show, ‘Some Sort of Grace: A Relationship’, presents work of Wojnarowicz and Hujar in a way that embodies the support the two men derived from each other; Gracie Mansion’s ‘The Boys Go Off to War’ focuses on Wojnarowicz’s Captain Fury images in which the artist is sometimes the soldier fighting the world, sometimes the victim under attack. These far smaller shows go farther in demonstrating Wojnarowicz’s complexity and potency, precisely because they mix a wide variety of media as the artist would have done, letting the imagery, not the materials, take centre-stage.

‘Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz’, The New New Museum, New York January 21 to April 11 1999. ‘David Wojnarowicz, The Boys Go Off to War’, Gracie Mansion, New York January 21 to February 27 1999. ‘Some Sort of Grace: A Relationship’, PPOW, New York January 8 to February 6 1999. ‘David Wojnarowicz, “iconographer”’, Adam Baumgold, New York January 21 to March 6 1999.

Barbara Pollack is an artist and writer living in New York.

First published in Art Monthly 224: March 1999.