Profile

Terre Thaemlitz

The Minnesota-born, Kawasaki-based artist, writer, DJ and composer explores gender and systolic systems, and argues against reconciliation

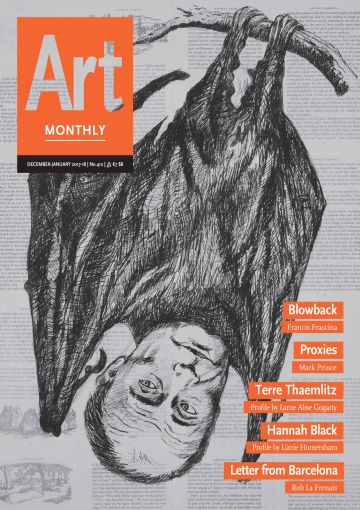

Terre Thaemlitz Lovebomb/Ai No Bakudan 2003-05

Terre Thaemlitz is a writer, deep house DJ, artist and composer; she also runs Comatonse Recordings from her adopted home of Kawasaki in Japan, where she moved from the Bay Area in 2001. Across Thaemlitz’s composition, video work and DJ sets, the collage form of her work never settles or reconciles, an aesthetic that also maps onto her politics. Amid what has become an increasingly fraught set of debates on gender and feminism, Thaemlitz’s work sounds out a militant and somewhat nihilistic note, stressing that there can be no reconciliation with one’s gender under current conditions. Thaemlitz identifies as a queer, pansexual, non-binary, non-essentialist trans person who consistently switches pronouns between he and she. As he explains, because the ‘he/she/he/she rotation is disorienting and annoying to most everyone, I feel I am inviting the reader to share in the awkwardness and inconvenience I continually feel around issues of gender identification’.

In relation to liberal, ‘born this way’ narratives around sexuality that have guided increasing recognition and acceptance of LGBTQ+ struggles, alongside recent events which would seem to prioritise the permission of trans people to join the military as the forefront of struggle, Thaemlitz’s writing stands as a vital source. Her 2015 manifesto ‘The Revolution will not be Injected’ cautions against belief in self-actualisation under current conditions of patriarchal, racial capitalism and opens with the statement that ‘You will not be able to gender reconcile, sister’. His critique takes aim at figures such as Caitlyn Jenner, whose dominance within trans narratives is underpinned by her conservatism and promotion of individualised quests for success. Thaemlitz also excoriates the art world and academia; my first encounter with her was at Tate’s ‘Charming for the Revolution’ symposium in 2013, where he heaped scepticism on the event’s legitimisation of talent, charm, camp and other categories of gender non-conformity that have been more easily digested by the mainstream media. As she writes, ‘The revolution will not be brought to you by the Guggenheim, Whitney, MoMA or Tate, and will not star Jack Halberstam reading Gaga Manifesto then preaching mob mentality by quipping “a million people liking Lady Gaga must mean there’s something to it.” The revolution will not thank wealthy patrons of the arts.’ As a result of such diatribes, Thaemlitz cuts a frequently solitary figure, both in her unrelenting refusal towards self-congratulatory gestures of diversity and ‘criticality’ within the art world, and in his role as one of few voices within the dance music world that speaks in an actively political tone. Theoretically, however, Thaemlitz’s analysis relates to the history of Marxist-feminist thought on reproduction, love and the family, as well as trans perspectives that emphasise gender abolition rather than reconciliation, a body of thought providing sustenance for continuing struggles.

Thaemlitz’s current exhibition at Auto Italia in London presents Interstices (2000-2003), an electroacoustic audio/video installation and a text-based work made in collaboration with Michael Oswell which reproduces his liner notes from the original recording of Interstices, released in 2000 on the now-defunct label Mille Plateux. Across Thaemlitz’s work as a DJ, composer and artist, her practice rests on collage, with Interstices developing a technique she calls systolic composition. The word systolic in this context reaches out in two interrelated directions: on the one hand, drawing from the prosodic definition that describes the contraction of a syllable to achieve metrical regularity, and on the other, in reference to the ventricular contraction of the heart. Thaemlitz’s systolic method contracts sound sources to produce new compositions, usually erasing the most recognisable vocal parts. For example, in Interstices, the frustrated snatches of Nina Simone’s ‘Wild is the Wind’ ring out, her voice never breaking through, meaning that the sound is both frustrating and tantalising. On the 1964 live recording of ‘Wild is the Wind’ that Thaemlitz subjects to systolic contraction, my favourite moment is where Simone utters an odd ‘ahemmm’ at the end of a passage. Interstices releases that utterance, before the sound gives way to an abrasive alarm.

Interstices opens with a black screen and a voice-over of a woman calmly describing her administering of a dildo to a man, who exclaims in both pain and pleasure. The video then proceeds to a cut-up audio montage of jazz, funk and disco as flashes of imagery punctuate the black screen. The voice-over exclaims ‘you’ve almost got the whole thing in your butt, honey!’ as the volume alters rapidly. Throughout, a refrain goes ‘there was a girl, there was a boy’, with the sound of these lines increasingly slipping out of sync as the video progresses. As the sound falters and layers, the accompanying pixelated shot of a couple kissing also blurs, producing a dreamy, foggy chorus that is interrupted by extracts from chat shows and pornography. Throughout the video, surgery forms an interstice between people, with a voice-over explaining how ‘his double mastectomy was the same operation his mother received under the recommendation of her oncologist’. Moving forward, we hear voices discussing surgery for intersex children that range from the fearful, ‘if you have intersex they’re gonna cut you’, to the critical, ‘the parents’ goal was to pre-emptively reconcile the desires of the child’. The medical profession is scrutinised, ‘help the doctors score points professionally’, and other voices sound out a quizzical tone: ‘exactly what is my opposite sex?’ Painfully, we also hear that ‘they detested their parents and hated the doctors, they were ruined people’. Some of these utterances play over so porn: a woman roleplaying a nurse caresses her body then undresses, before ‘paid in full’ appears as an inter-title on screen. Elsewhere, talk show extracts ring out, with the title ‘Help! ... Turn my tomboy teen into a ravishing Queen!’ appearing alongside the logo ‘Terre’, mimicking ‘Ricki’, ‘Maury’ or ‘Jerry’.

A week prior to visiting the exhibition at Auto Italia, I saw Thaemlitz play as DJ Sprinkles at Panorama Bar in Berlin. Sprinkles performs in what Thaemlitz calls ‘boy drag’, a decision emerging from his time as the resident DJ at Sally’s II, a New York transsexual sex-worker club during the early 1990s. The ease of physically resting into the soulfulness of Sprinkles’ set was persistently undercut, antagonising the pervasive mythic structure of the nightclub as a space of release and gratification. At one point he released samples of domestic violence which, though inaudible in terms of their specificity, directed a violent pitch against the deep house his set was dominated by. This gesture is less about juxtaposition for shock-value, and perhaps more an attempt to antagonise the severance of house music from its origins in black, brown and queer communities. Violence appears in order to memorialise the violences those communities were and still are subjected to, with Thaemlitz writing that his DJ sets stand as ‘attempts to publicly carry forward these long dead musics that were the soundtrack to a lost era of queer/HIV-AIDS/trans-activism’.

Thaemlitz’s electroacoustic audio and video installation Lovebomb/Ai No Bakudan, 2003-05, was recently presented in the Museum für Sepulkralkultur at Documenta 14. Lovebomb/Ai No Bakudan engages with the ideology of love in popular music and beyond, drawing in Thaemlitz’s adolescent experiences of homophobic bullying, the history of lynchings in her hometown of Springfield, Missouri, the fascism of Futurism, as well as samples from radio broadcasts made by the ANC. Visually, these sources are rendered through photographs, Thaemlitz’s drawings and video footage, and, as with Interstices, collage, which also underpins the audio component. If Lovebomb/Ai No Bakudan operates under the principle that ‘rather than songs of love and unity, I long for audio of love’s irreconcilable differences’, Thaemlitz’s 2012 multimedia album Soulnessless critiques appeals to the ‘soul’ and spirituality in music and religion. Soulnessless stands as the longest album ever recorded, released on 16GB microSD card with accompanying text and video. Closing with a 30-hour canto entitled ‘Meditation of Wage Labor and the Death of the Album’, Soulnessless also stands as a response to the increasing demands for endless content, often freely provided, within online commerce and culture. Viewed alongside the ever-proliferating and often naval-gazing debate on artistic labour within the art world, the Soulnessless project stands as an all too rare aesthetic – rather than only discursive – attempt to grapple with the conditions of overproduction and free labour.

If Thaemlitz’s practice tends to rely on a set of formal procedures rooted in collage, the stakes of this lie in opposing collage’s dominant, contemporary function of presenting a postmodern medley of never-ending, equally appealing and interchangeable aesthetic and political choices. Instead, Thaemlitz situates collage as an argument, a footnote, homage and critique, with these different registers refusing reconciliation and appeals to organic wholeness. What this demands of the viewer is attention and a clarifying of one’s position, a request that rings out as a real challenge to art’s pluralistic absorption and domestication of radical politics. Thaemlitz’s precision of form demands precision in politics, and her precision in politics demands precision in form. Like her switching between pronouns as a challenge to the idea of gender reconciliation, this process invites the reader/listener/viewer to share in her demands.

Larne Abse Gogarty is a writer and art historian.

First published in Art Monthly 412: Dec-Jan 17-18.