Reports

Speculative Libraries

Nick Thurston on libraries as artworks

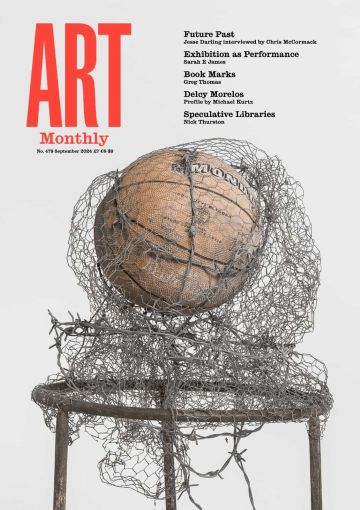

a selection of printed matter from Personal Libraries Library and Press

An A5 manilla envelope has just arrived. The back side has three US postal stamps plus my name and address penned in familiar handwriting. In the top left is a sender’s stamp from Vermont that fills me with excitement. This is my annual bundle of printed matter from the Personal Libraries Library & Press (PLL), a subscription lending library and micro-publisher run by the US artist Abra Ancliffe. Every bundle contains printed matter made by Ancliffe and a simple bibliography that lists the source material she drew to make the prints as well as the item indentifier that indexes each new print in the project’s catalogue.

Ancliffe began PLL in Portland, Oregon, in 2009. She came across a catalogue that detailed the private book collection of a 19th-century astronomer, naturalist, educator and librarian, Maria Mitchell, and set out to collect the same set of books in order to retrace Mitchell’s interests. Ancliffe has been doing the same ever since by following public records of institutionally catalogued libraries that belonged to other people she admires, including Robert Smithson and Italo Calvino. PLL aggregates partial duplicates of personal libraries, plus the printed matter Ancliffe produces by sampling those collections, into one public artwork.

Ancliffe’s ‘mirror collections’ are incomplete and constantly expanding – she does not have the money or time to complete them – contrary to the classical fantasy of ‘The Library’ as something complete, stable, objective and authoritative. This fantasy still haunts the collective imagination of dominant communities in the so-called ‘developed world’, underwriting popular idealisations of what libraries could and should be. For example, it shaped the initial mission statement for the biggest self-proclaimed library of our age, Google: ‘to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful’.

Like Google, PLL’s catalogue is freely available online. Unlike a search engine, however, you cannot pull up digitised copies of PLL’s holdings via search returns. Instead, Ancliffe started sharing her collections by turning the living room of her family home in Portland into a public reading room that anyone could visit during scheduled hours, and from where members could borrow books. She continues to do the same from her studio and print workshop in Vermont.

The availability of the library operates backwards from Ancliffe’s home life. It is neither permanent nor constantly available. It is an imperfect but functioning public resource whose rationale was invented as a speculative act of composition – these are mirrors of libraries that already exist elsewhere, so PLL does not serve a social or scholarly need, per se, at least not primarily. Instead, it explores the subjective choices and situatedness of its librarian, embracing rather than denying the vulnerabilities of doing so, in a manner Ancliffe self-identifies as ‘nested authorship’.

This term is particularly popular in bibliology. It is used to describe the creative contributions of people (authorship) to frameworks or production processes (nests) that also involve the authorship of others and acknowledge the fact. Think of the woodcutter who illustrates a treatise or, for that matter, the librarian who creates a catalogue from books written by others, then samples their words and images through collage and reprography. Framing Ancliffe’s librarianship as ‘nested authorship’ helps me to understand PLL as an open-form artwork, by which the thing composed is a library – the library-ness of which is actual, in that it functions as such. This is the library as artistic form and artist as librarian. PLL is a beautifully modest example of what I am calling speculative libraries.

Ancliffe’s way of making is only possible because she collects filtered sets of available publications rather than unique or rare artefacts. That difference typifies an important distinction between speculative library-making and its sibling practice, ‘the archival impulse’. Hal Foster coined that phrase to bracket the still-growing number of artists who focus on revealing histories through material objects that can be organised into tranches, enabling their counter-historical symbolic value to be indexed against the systems of knowledge production in which they had been buried.

This mnemonic drive to archival practice depends on organising the relationships between component parts. It creates a kind of distributed unity that inclines the outcomes to appear as installation art, or lends them to sequential media like books or video. Speculative libraries often appear to have the same look and tendency. Yet, for a library to keep being a library it has to keep changing, for reasons made clear by the modern distinction between archives and libraries. Archives are repositories of historical material that may or may not have been published but is often rare or unique. Libraries provide public access to published materials that are deemed of current use to that library’s usership, be those materials old or new. An archive can be complete or finished, but no library ever can.

The two offer different kinds of access to different kinds of material. While an archive preserves its holdings – is its holdings – a library is really an informatic structure – it is a cataloguing system with the capacity to organise, retrieve and update current holdings. Preservation, even conservation, are important to any library, but the thing being preserved is the integrity of access to copies – publication is a process of editioning, after all – not specific artefacts. Archives connect people to documents and objects. Libraries connect people to publishing cultures.

There is a difference between artworks about libraries and artworks that are libraries. I have been obsessed with the latter for nearly two decades and have made at least five of them, too, sometimes as an artist, other times as a curator, but always with the amateurism of a repressed librarian. To manage my obsession, I developed a crude typology of the different ways artists find to materialise or enact the basic essence of a library – the cataloguing principles – in a specific time, place and offer: the form of a library. I use this typology to gauge the relative degree to which something functions as both an artwork and a library, given that few really try to do both, and even fewer do them both well. My typology is best pictured as a sliding scale, and it runs like a wedge from the thinnest correlation (one or other) to the thickest (both).

At the thinnest end are library-related artworks we can call ‘symbolic gestures’. In these artworks, a library, library culture or ‘The Library’ are subject- matter in artworks whose form is clearly something else – be that a painting, sculpture or performance etc – and whose generic mode is clearly otherwise, be it narrative, memorial or documentary etc. For example, think of Kader Attia’s Continuum of Repair, 2013 (Interview AM448). This installation is structured by a quadrant of floor-to-ceiling storage racks lined with books. In the central well between the racking, prop-like scientific instruments feature in a display cabinet topped with an upward-facing mirror which, reflected in the ceiling mirror above, creates the illusion that this ‘library’ for science and religion goes on forever as an infinite upward extension of knowledge, or Jacob’s ladder. This is a Babel-like fantasy of the total library, dramatised as a static monument. Or, think of Emily Jacir’s amazing ex libris project, for which, between 2010 and 2012, she used an old mobile phone to secretly photograph inscriptions found in books catalogued as ‘A.P.’ in the Jewish National Library in Jerusalem. Those photographs show marginalia, scribbles, names and stains. Displayed as prints, Jacir’s snapshots magnify these traces of the books’ owners before they were looted from Palestinian homes, libraries and institutions during the expulsions of 1948, then misleadingly accessioned into the Israeli catalogue as ‘Abandoned Property’.

Symbolic gestures can be a powerful and concise way of communicating the value of libraries. For example, Ross Birrell’s elegiac film trilogy, A Beautiful Living Thing, 2015, studies musicians and dancers as they respond to the charred remains of Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Library after it tragically first burned down in 2014. Unsurprisingly, such gestures often circle back to artists’ expanded attitude towards publishing practices, usually treating specific libraries as a case study for a broader critique or allegory. For example, Fehras collective’s When the Library was Stolen, 2017, is a multilingual book that catalogues the c10,000 publications owned by Abd Al-Rahman Munif, which were stolen from the late-Saudi writer’s home in Damascus in 2015 (Profile AM448). By itself, Munif’s book collection maps his connectedness with cultural and political movements across the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. When prefaced by a set of texts and photos, this list also opens a broader discussion about the particular role private libraries have in the Arab world, as a hub for sharing publications outside state-controlled contexts.

The tier on my sliding scale in between such symbolic gestures and all-out speculative libraries is an amorphous in-between zone, neither one nor the other. I simply call it the ‘grey area’, partly because what defines this type of work is vague, and partly because that vagueness has the same troublesome impact that so-called ‘grey literature’ has on cataloguing standards. Grey literature is produced by and for special-interest communities and does not fit neatly into current indexing or database categories. The library-artworks in my grey area tend to hover between being a library item and being representations of a library or libraries. They propose ‘nearly libraries’, hidden libraries and the like.

Douglas Gordon’s A Relationship Between Books, 1997, is a great example. This is a real but out-of-reach library. Its public exhibitable form is an exchange of letters and contracts that explain and announce its existence. Those documents tell us that between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1997, Gordon (Interview AM262) had a pot of money made available by the collector Bernhard Starkmann to buy two copies of every book he found interesting. Gordon kept one copy and posted the other to Starkmann. Their libraries grew as twins until the funds were exhausted. Its full form, as an artwork, is the pair of documents that announce its existence plus the two mirror collections, physically separated, off show and still in use by their respective owners.

Another great example is Mike Nelson’s An Invocation, 2013. Nelson (Interview AM278) was commissioned to make a permanent work for Focal Point Gallery when it moved into a new shared building with Southend Central Library. He selected 530 books already due to be deaccessioned from that library’s collection, then stacked them inside the cavity of one of the new building’s walls, entombing them in the very fabric of the place – forever present but out of sight. The only key to their presence is a 1,056-page softback artist’s book that features 1:1 scans of the front and back covers of all 530 volumes, recompressing their trace as one new volume apt or libraries to purchase. Nelson’s nested collection of cast-offs is protected from further threat of pulping yet deadened for readers by the very same gestures.

Grey area library-artworks often function as site-specific interventions in existing libraries, levering some new way (conceptually or emotionally, or better yet both) for us to understand that library’s place in wider ecosystems of culture, education and heritage. Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s Scoring the Stacks, 2019, for Brooklyn Public Library is one beautiful example of just such an intervention. These notational scores prompted visitors to move around the library in unusual ways, encouraging them to treat the architecture and holdings as play spaces for embodied modes of reading.

Beyond the grey, at the thick end of my sliding scale, are speculative libraries. Like Ancliffe’s PLL, they are functioning libraries – and so are open-form, in formal terms – and composed as artworks, in that the artist-librarian speculatively proposes cataloguing principles and enacts them. I could wax excitedly about such works by CAMP, Chimurenga, Sean Dockray, Temporary Services, Dexter Sinister, Eva Weinmayr and many more. Instead, I want to signpost two examples that appear quite different from one another, and to think about them as practices that powerfully demonstrate the different aesthetic and political horizons of speculative libraries.

The first example will probably be the most familiar, Katie Paterson’s Future Library, 2014–2114 (Profile AM338). Annually during the project’s 100-year term, a different acclaimed author from around the world donates a new short-form manuscript to the project, which is kept safe and unread in a tailor-made space called the Silent Room in a new public library in Oslo. Just outside the city is a forest of 1,000 saplings. In 2114, these trees will be felled to create the paper on which an anthology of all the currently secret manuscripts will be published. Until then, public information and annual donation ceremonies build commitment and expectation on a scale no one can selfishly measure. Paterson’s project makes a promise to the future, tethered to arboreal time rather than the life expectancy of the authors, commissioners or audiences.

Lastly, think of Memory of the World, 2011–, a digital-first library developed and maintained by Marcell Mars and Tomislav Medak. This project grew from the collaborative milieu of MAMA in Zagreb, a space opened in 1999 to explore the role of multimedia art in the region’s shift from a socialised property regime to capitalist property relations. Memory of the World is a ‘shadow library’ – a publicly available database of pirated digital copies of books, and one the biggest in the world for arts and humanities publications. Through exhibitions, publications, workshops and social scanning events, it provides a stable online repository for an infinite number of remote librarians and allied projects, including Pirate Care, 2019– (Profile AM440). This library of libraries offers a public infrastructure that radically increases access to books beyond the inequalities governed by copyright laws.

I am not a historian of art or of anything else. I have no idea if speculative libraries are a new phenomenon – though I doubt they are, for what it is worth. Any librarian reading this might well scream, ‘All libraries have to be imagined and created!’, which may be true but is only half the burden. Speculative libraries pose a double-barrelled question, challenging our ideas about what libraries and art can be, separately or together. As two quite different proposals, Future Library and Memory of the World both suggest that no single model should ever regulate the culture of either art or libraries. Singular fantasies of authority are just that – fantasies – better left to despots and tech corporations such as Google.

Yet, it is easy to guess why speculative libraries may matter now more than ever. I am chipping away at this essay right after the UK general election. New PM Keir Starmer has just promised a government built on decency and a commitment to public service, qualities more readily associated with civic library culture than Parliamentary life since the Public Libraries Act of 1850. Starmer has a lot to do. One headline in this weekend’s Observer reads, ‘End of the librarian? Council cuts and new tech push profession to the brink’. Public libraries have been closed or stripped with a numbing indifference by local authorities trapped by successive governments that have been caught between the twin death drives of neoliberal state economics: excessive borrowing and austerity measures.

Weathering this storm has been too much for many library networks. The same storm will be too much for many public art galleries, too. Everyday life is repeatedly teaching us that the all-engulfing ‘permacrisis’ is, in no small part, a wholesale crisis of publicness. I cannot get an NHS dentist, trust the security of the pension pot I am obliged to pay into, or vote in my constituency for a meaningful alternative to centrist candidates. The current civic sphere distorts rather than reflects the shared future many would like to contribute towards.

In January this year, Baroness Welton reported the findings from her independent review of English public libraries. Headlining eight recommended strategy changes were four themes of concern, which I paraphrase: (1) a lack of recognition across all levels of government about the work libraries do; (2) a lack of general public awareness about what modern libraries offer; (3) a lack of data recording the impact libraries have; and (4) a lack of clarity about what government wants from our library network. Libraries are vulnerable and expectations of them are unclear or contrary. The same goes for public art and public art galleries. Allyship seems essential, at least at the civic level.

I would never suggest that art can solve this problem or any other. But I do think speculative libraries are one unique way of proposing different futures for our library cultures, and to change, in turn, the fabrics of our publishing and educational cultures, which libraries quietly line. In short, libraries can always be reimagined and art can be one way of figuring out how.

Nick Thurston’s project for the Artists’ Books Library at Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong, runs September 2024 to February 2025.

First published in Art Monthly 479: September 2024.