Profile

Rosa-Johan Uddoh

Chloe Carroll shows that the artist’s background in architecture enables her to interrogate the identarian influence of cultural spaces

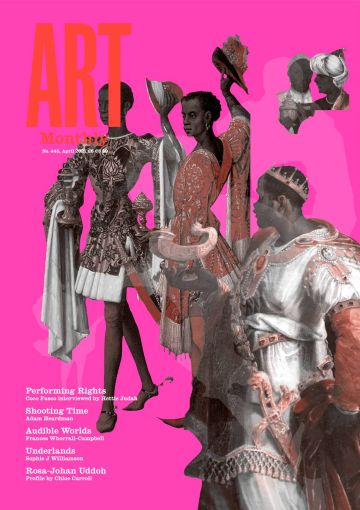

Rosa-Johan Uddoh, Performing Whitness 2: Mews, 2020

‘Hello David Duckinfield,’ pronounces a suited, red- lipsticked reporter in Performing Whitness 2: Mews, 2020, co-produced by East London Cable and filmed in the echoing galleries of Tate Modern. ‘I’m Rebecca Jones. I’m Joanna Gosling. I’m Elizabeth I with Naga Munchetty. One of these women with messy handwrit- ing.’ This anchor with many names, who stands ahead of two glamorous assistants dressed in sparkling blue jumpsuits, is performed by Rosa-Johan Uddoh. She is the vessel for a broadcast, an impartial mouthpiece for nebulous yet indisputable ‘facts’. The assistants are her chorus, finger-clicking on cue and punctuating her announcements with sharp, soulful flashes of song (‘tonight!’, ‘we’ll hear from the families!’, ‘it’s Friday!’). In today’s dispatches, we are told: Arsenal have sacked their manager, Elizabeth I; the Magna Carta has been charged with complicity; the suspect, who was wearing the prime minister, has died at the scene. Life in the UK goes on. These rapid-fire fragments of nonsense news lay bare the ways in which the performance of an objective voice might repackage conditions of absurdity into something familiar, routine. ‘Looking forward to that, Gavin,’ the unblinking Rebecca/Joanna/Elizabeth pronounces. ‘Praising the monarchy.’

The newsreader is one of a troupe of recurring personas embodied or studied by Uddoh throughout her investigations into what she describes as ‘the imperfect colonial subject’. Members include presenter Moira Stuart, writer and broadcaster Una Marson, fictional detective Hercule Poirot, the Duchess of Sussex Meghan Markle, tennis superstars the Williams sisters and a ‘mouthful of chicken’. As much a concern as these characters, however, are the spaces they inhabit, from the newsroom to the gut. Belly of the World, a 2019 performance, tells of the queasy porosity of self and environment. Uddoh, lying draped across an elegantly set dining table, plays the dual role of dinner party host and ‘diasporic morsel’. She describes food perched on the threshold of the tongue, moving through the ‘semi-public cavity and private insides’ of her body, before it continues on its way through the city sewers: a fugitive.

Having preceded her artistic training at the Slade with an architecture degree from Cambridge University, Uddoh is acutely aware of how bodies are conditioned by space; how these apparently discrete systems intersect and form one another; how spaces encode colonial logics. She is well acquainted with the ways in which the neoclassical vernacular of elite educational institutions and the colonial architec- tures of urban centres actively manifest structural oppression on the marginalised bodies which pass through them – if they are not stopped at the door.

Navigation of these spaces is shown to be a labour in itself. Built 4 Love, 2019, performed at Nottingham Contemporary with diasporic dance troupe DIDD (Department for International Dance Development, of which the artist is a founding member), stages a gleeful destruction of these architectures. Diana Ross’s 1979 disco-reggae classic ‘It’s My House’ provides a soundtrack to the demolition of human- sized paper effigies representing Corinthian columns, the Shard and the Millennium Dome by the three young women as they dance defiantly, outfitted in bright satin pyjamas. In The Serve, 2019, Venus Williams ‘becomes a space-building agent’, a carrier of embodied knowledge and purveyor of the 207.6km/h serve. For Tile House, 2018, the artist tiled a roof with earthenware clay cast on the thighs of black and brown womxn, a response to an old Cuban myth that roof tiles in the city of Havana were once made by female slaves in the same way. The resulting shelter, made both of and for historically exploited bodies, is a reclamation of violent colonial fantasy which proposes not just new structures, but new tools with which to build them. Because, as Uddoh once sang in 2018 among Tate Britain’s Henry Moores, ‘the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house, babe’.

New tools in hand, she reaches back through the histories of British pop culture and media, hacking and reassembling their narratives as she goes. Commissioned as part of an upcoming solo exhibition at Focal Point Gallery, in Windrush: A Tongue Twister, 2021, Uddoh uses word play to tackle the perpetua- tion of British nationalism and racism through UK school curricula. A group of pupils are invited to read well-known twisters, which have been reconstructed by Uddoh. ‘Black Britain became big 1500 years before Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled pepper from the Seychelles,’ they recite. You may recognise Peter Piper from such starring roles as ‘famed pepper thief’, advocate of ‘Practical Principles of Plain and Perfect Pronunciation’ and – surprise – ‘18th-century French colonialist-horticulturalist and government administrator of Mauritius’. Uddoh pulls this latent strand of colonial ideology out at its root; an ideology bound up with the politics of articulation. Who is deemed articulate? What is deemed worthy of articu- lating? A concealed figure is exposed in the pedagogi- cal machine.

These concerns can be traced back to Uddoh’s 2019’s video Black Poirot in which Agatha Christie’s iconic inspector is loosely recast as Martinican writer Édouard Glissant. Known primarily for his 1990 text Poetics of Relation, Glissant argues for a right to opacity for all, a resistance to the demands of legibility imposed on the colonial subject. The labour of Black Poirot, like the artwork itself, enacts a careful ‘tracking of phenomena’ and of ‘encounter- ing a past that is not past’. Echoing Christina Sharpe’s theories around wake work, Uddoh’s inquiry sees Black Poirot transformed from detective to clue on the trail of the great ‘Western epistemo- logical project’, a ‘colonialist plot’ that insists on constant interrogation. ‘Why? What? Who? Whodunnit?’ Uddoh toys with the narrative trope of the murder mystery, even pantomimes it by amplifying such hackneyed traits as the high-society setting, the testimony of the maid and the gathering of the family in the parlour for questioning. All this amounts to a sort of absurd witness sketch: that’s him! That’s the man who picked my peck of pickled peppers! In the end, however, Uddoh resolves: ‘I decide to do some investigation of my own.’

In Auto Cutie, 2019, we see Uddoh return to her newsreader guise, reading from this makeshift teleprompter held at each end by a member of DIDD. A scroll unfurls through the cramped quarters of a south-east London gallery, carving its winding path through the space, encircling a portion of the audi- ence like a hungry paper serpent. The text splices together the story of the 17th-century discovery of Cuba’s Virgin of Charity by three slaves off the Bay of Nipe with that of Moira Stuart’s first televised appearance on BBC News, four months after the start of the Brixton Riots in 1981. ‘This is thought to be the first time many people in the United Kingdom have believed a black woman,’ Uddoh reports. Both the broadcast of the national news by Stuart (at a time, the artist has pointed out, when many British households would not have allowed a black person into their living rooms) and the chance encounter of a drifting effigy carry the miraculous charge of an apparition.

Staged as part of Uddoh’s solo show ‘Studies for Impartiality’ at Jupiter Woods in 2019, the work forms part of her investigation into the specific labours of black performance. Drawing from Stuart’s minimal facial choreography – a raised eyebrow here, a slight, reassuring smile there – and steady, meas- ured voice, she mines the murky space between impartiality and complicity. In the enduring colonial quest for evidence, transparency and objectivity, the newsreader becomes a vital agent, and Stuart – like Black Poirot – becomes a clue.

In Uddoh’s work these lines of inquiry often lead back to the archive, where colonial spatiality and epistemology converge, and black, queer, female voices find themselves excluded, unmarked or seques- tered in dusty, neglected corners. Black Poirot quotes Saidiya Hartman’s 2008 essay ‘Venus in Two Acts’: ‘The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them.

So it is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none. To create a space for mourning where it is prohibited. To fabricate a witness to a death not much noticed.’ One of the new works on display in Uddoh’s upcoming exhibition at Focal Point is a billboard-sized collage depicting an enormous congregation of Balthazars (one of the three biblical Magi who visit the infant Jesus in the Christian nativity, and one of the first historically black roles in western literature). They are gathered as if in protest, depictions united across ages, media and styles, and arranged, the artist tells me, in friendship groups. Uddoh has created a marching archive, on its way to redress the narrative.

Rosa-Johan Uddoh’s ‘Windrush: A Tongue Twister’ is on Focal Point Gallery’s website until 25 April, her exhibition at the gallery is scheduled 19 May to 29 August. Uddoh’s work is also part of the group exhibi- tion ‘Brand New Heavies’ at Pioneer Works, New York, 2 April to 20 June.

Chloe Carroll is a writer and curator based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 445: April 2021.