Review

Radio Ballads

Maria Walsh encounters socially engaged artworks in an east London council office and a west London royal park.

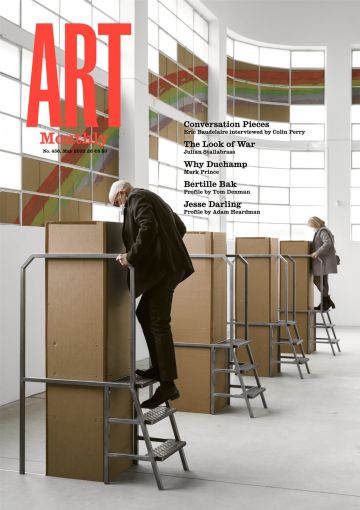

Illona Sagar, The Body Blow, 2022

Taking its cue and title from the original Radio Ballads, a series of eight radio plays created by musicians Ewan McColl, Peggy Seeger, and producer Charles Parker and broadcast by the BBC from 1957–64, this exhibition is the public iteration of a three-year research project during which Sonia Boyce, Helen Cammock, Rory Pilgrim and Ilona Sagar were embedded in social care services and community settings in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Curated and produced by the Serpentine’s Civic Projects team – Amal Khalaf, Elizabeth Graham and Layla Gatens – in partnership with New Town Culture, a curatorial initiative led by the borough’s Culture & Heritage Service, four new film commissions are shown simultaneously at Serpentine North and at Barking Town Hall and Learning Centre, albeit to different effect.

At Serpentine North, the films are shown using state-of-the-art LED screens or projection, with supporting research material being sporadically presented on gallery walls or displayed in carefully placed vitrines in an almost feng shui-like manner. While their content is derived from social issues from mental health and domestic abuse to asbestos poisoning, the films are not simply documents of extensive research processes, but artworks inscribed with each artists’ signature styles. And here lies the rub. While I have no doubt about the transformative nature of the collaborations for care providers and receivers, the artists and the curatorial team, what does it mean to lift them out of their life worlds for peripatetic gallery-goers in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea? Also, while the original Radio Ballads combined song and music with stories of communities whose voices were rarely heard in the media, particularly workers’ struggles and resistance, today’s airwaves and blogospheres could be said to be clogged with such stories. What kinds of telling and listening can art contribute?

While the films hold their own integrity, in some cases they infer that something more significant has gone on elsewhere. A case in point is Cammock’s Bass Notes and SiteLines: The Voice as a Site of Resistance and The Body as a Site of Resilience, 2022, an experimental documentary that intersperses footage of collaborative workshops involving Cammock and run with Pause, an organisation that works with women who have had their children removed from their care, with footage of Cammock’s single-hued colour fields replete with fragments of crisp poetic text and prosaic theoretical musing voiced over cloudy skies or architectural scaffolding, the images seeming analogies for psychic conditions of wholeness and distress. Cammock cleverly avoids giving the viewer a bird’s-eye view of the workshops, which involved movement, singing and meditative art activities for both care receivers and givers. The edit often focuses on things to the side of these (a sleeve, the back of a head, interior architectural details, a stack of institutional blue chairs), while the group work is shown in a loosely decentred way that honours its life world. The installation also consists of a display of heavy-duty theory books around care, a freely available artist’s booklet, a vitrine containing line-drawing exercises, a fabric banner and some screenprints, all of which seemed like footnotes to an elsewhere. However, the sequence of static camera portraits near the end of the film in which participants pose in self-chosen assertive guises testifies to a process of care which partakes of ‘quotidian’, ephemeral moments of give-and-take rather than care being an object to be administered.

Boyce, too, finds ways around the ethical question of what it is to voice the traumatic stories of others by not giving the viewer central characters or figures to objectify and/or empathise with. While empathy can be a first step in recognising another, it can also be of way of fixing another as an object of pity and not hearing them. Set against a wallpaper backdrop, Broken, 2021, which consists of a repeat pattern of a cartoonish drawing of a smashed car windscreen, an emblem for abuse, the four-channel video Yes, I Hear You, 2022, shows group bonding gestural dance movements between four self-identified domestic abuse survivors – indirectly, a son, a friend; directly, two women. At points in the short (at just over 12 minutes) video, each participant is singly portrayed, two choosing to face the camera, the others turning their backs and addressing the theatrical red curtain signposting the video’s performative framing. The soundtrack voices four first-person narratives exploring the conflictual feelings involved in abusive relationships, while a set of digital screenprints also conveys these stories either by a single word, eg ‘survivor’, or in longer paragraphs, but it was only at the exhibition of the video at Barking Town Hall that I could actually hear them in any deep listening sense. Presented, as were the other films, using the council building’s built-in projection facilities, Boyce’s single-screen version of Yes, I Hear You was less visually seductive. Emitting from an ordinary speaker in the darkness of a bare office, the voices had a more phenomenological resonance that allowed me to feel between the gaps of the constructed scripts, distillations from transcripts of the dozen or so interviews Boyce conducted as part of her research.

Sagar’s The Body Blow, 2022, taking its title from one of the original ballads, is a two-channel experimental documentary about and made in collaboration with people suffering with asbestos-related cancers, Barking and Dagenham having the highest level of these diseases in London due to its colonial trade connection with the Cape Asbestos Company. Combining archival footage, present-day shots of Barking’s post-industrial docklands, and interviews with several actors (social workers, lawyers, medical professionals and people with lived experience of the diseases), the film’s reportage is pensive, with slow-paced tracking shots and a softly thrumming score adding to its atmosphere. More experimental sequences digitally manipulate what look like body scans to simulate materialist film over which a man’s voice on a landline chokingly describes the daily grind of being caught between social and medical services. The Body Blow is engrossing, informative, but I wondered what, if any, is the difference between watching this film in a gallery space and watching it in a TV slot such as BBC4’s Storyville? A provisional answer to what would be missed in a single-screen viewing emerged during a sequence in which participants of the London Asbestos Support Awareness Group, with whom Sagar collaborated on the script, perform hand movements and breathing exercises to slow down the breath. ‘Breathe in, breathe out’; these exhortations registered in my body, a relation to those afflicted with asbestos-related cancers and mesothelioma, felt not via the gaze but via the two-channel film, which itself operated as a kind of breathing apparatus, its diaphragm moving between the microscopic intimacy of bodily interior damage and the panoramic exteriors of decaying urban infrastructures.

Pilgrim’s RAFTS addressed environmental concerns via the lens of mental well-being. A collaboration with many project partners, the film loosely takes the structure of the original ballads in being organised around seven songs and comprising eight chapters, each one featuring a resident of Barking and Dagenham involved with Green Shoes Arts, an organisation offering artistic and creative activities to vulnerable young people and adults. At 60 minutes, the film gets a little repetitious, each chapter usually beginning with a participant talking about the solace of parks and trees, followed by a concert in a church in which either the participant performs spoken word, or Pilgrim’s arrangements of their words are sung by a singer and choir to the accompaniment of the London Contemporary Orchestra, Pilgrim also featuring on piano and harp. Occasionally this bordered on the sentimental, but mostly the resonant voices shone through in ways that potentially connect viewers and subjects to the mutually life-enhancing spaces of nature, music and art. Here the screen itself is a kind of raft, a metaphor emphasised by Olga Micińska’s and Mathild Clerc-Verhoeven’s Held Together, 2022, the engraved wooden frame and other nautical paraphernalia surrounding it, Pilgrim’s installation generously showcasing other artists’ work, not least the stunning botanical paintings by Eddie Paggett, and a delightful animation by Catherina Rowland, both members of Green Shoes Arts.

A decade ago, there was concern in art discourse about socially engaged and relational art practices being used to shore up a failing state. Much has changed since, and what this collaboration between Serpentine and Barking and Dagenham shows is how both social care and art institutions are not only rethinking what and how they provide for multiple stakeholders across all spectrums of society, but also how they can learn from one another. That said, the curatorial decision to have one kind of exhibition for the borough and another for the art world raises more questions about audience and site than I can address here.

Maria Walsh is reader in artists’ moving image at Chelsea College of Arts and author of Therapeutic Aesthetics: Performative Encounters in Moving Image Artworks, Bloomsbury, 2020.

‘Radio Ballads’ was at Serpentine, London, 31 March to 29 May 2022 and Barking Town Hall and Learning Centre, London, 2–17 April 2022

First published in Art Monthly 456: May 2022.