Report

Radical Jewishness

Caspar Heinemann argues that curators have downplayed politics in Nicole Eisenman’s Whitechapel Gallery show

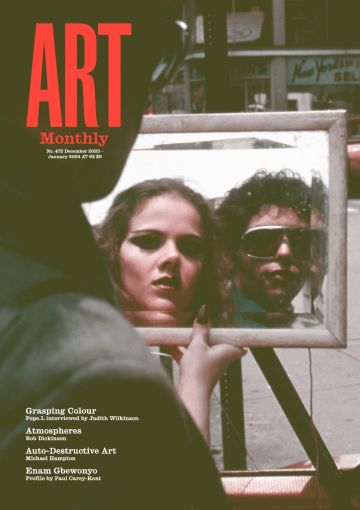

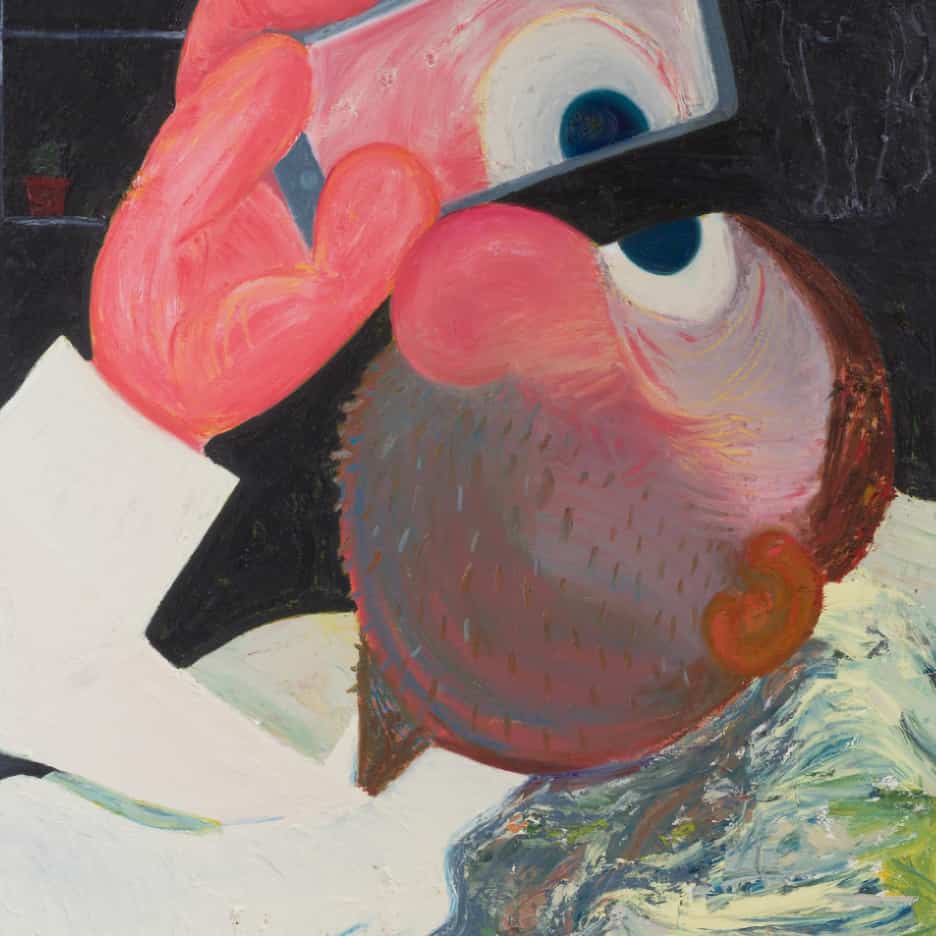

Nicole Eisenman, Selfie, 2014

The mood of Nicole Eisenman’s painting Seder, 2010, included in her Whitechapel Gallery retrospective ‘What Happened’, is one of alienated belonging. At the head of the family Passover table is a figure’s hands – possibly Eisenman’s – holding a piece of broken matzah like a Haggadah, as if desperately searching for answers, a narrative or meaning in the crumbs. The Haggadah, the text that gives structure to the Passover Seder, tells the story of the liberation of Jews from slavery in the land of Egypt, known in Hebrew as Mitzrayim, the ‘narrow place’. By placing the viewer – Jew and non-Jew alike – as a participant at the table, Eisenman suggests a universality to this closed practice, both the Exodus narrative itself and the sense of being both of and apart from a family unit, a culture – in the words of song-writer Daniel Kahn, ‘a Jew among the Jews’. This is an invitation to solidarity. Rather than reifying a cohesive identity position, one is instead encouraged by what philosopher Gillian Rose cited as her motivation for thinking through her Jewishness, a ‘speculative account of experience, which persists in acknowledging the predicament of identity and lack of identity, independence and dependence, power and powerlessness’.

The term Hebrew itself originates from Ivri, an ancient term for an Israelite. Ivri (which gives name to the Modern Hebrew language, Ivrit) is based on a root that means beyond, other side, or across. What it is to be a Hebrew is to be from beyond, from the other side, to have crossed over. The ethno-nationalist rhetoric of the project of the state of Israel has sought to occlude the fact that, contained within the name is the disavowal of borders, that the Hebrews were not from the land of Israel. Rabbi Arthur Green in his essay ‘Judaism as Counterculture’ writes on the overrepresentation of Jews in the creative and political Avant Garde of the 20th century as being a reflection of their own experiences as ‘somewhat insecure newcomers to the broader political and cultural realm’, post-Emancipation. He argues that the seemingly nonsensical linking of Jews to both communism and capitalism by antisemitic conspiracy theorists had some basis, as ‘the international banker and the international communist conspiracy both reeked of internationalism, opposed to the nativism of the ethnic-based nation-state’. Both in the case of communism and artistic modernism, Jews would become key contributors who were nevertheless ultimately marginalised, both inside and outside of the movements they helped to define. Green roots Jewish ethics not only in historical oppression, but also in the theological tenet that we are all equally made in God’s image, and in the yearly call of the Passover seder to ‘remember that you were slaves in the land of Egypt’ – not only a call to identify with the oppressed in all situations but also one that functions precisely because it is grounded in a specifically Jewish cultural framework. In an extraordinary piece for Jewish Currents on the current Israel– Hamas conflict, Arielle Angel writes that ‘we need to imagine a movement for liberation better even than the Exodus – an exodus where neither people has to leave’. It is a reminder that our specificities can, and should, lead to solidarity, rather than division.

A section of wall text nearby to Seder reads: ‘[Eisenman] began to harness the language of early 20th Century figuration and expressionism in her work – styles of painting associated with Vienna where her grandparents once lived.’ The paragraph goes on to quote Eisenman describing her painting of this period as reflecting ‘a sense of longing for another time and place’. What the paragraph fails to mention is that her family were Jews who were forced to flee Vienna in 1938 when the Nazis annexed Austria. The framing not only depoliticises Eisenman’s family history, but also reduces her own engagement with the artistic styles mentioned to one of passive nostalgia, rather than commentary or struggle. This is obviously conceived as the Jewish section of the exhibition, and also includes a painting of Eisenman and her psychoanalyst father surrounded by books such as Sigmund Freud’s Moses and Monotheism. We are presumably supposed to read between the lines to deduce this historical trauma via the paragraph’s later description of Seder (originally commissioned by the Jewish Museum in New York), yet Jewishness is never mentioned by name. The historical opacity of the framing deprives the average viewer of considering the possibility that a Jewish artist engaging with 20th-century modernist aesthetics may have a particular political resonance, or that the ‘longing for another time and place’ may not be simple nostalgia for her grandparents’ world but instead indicative of a deeper tradition of diasporic hope, of imagining an end to spiritual galut or exile. This omission only becomes more glaring as the exhibition continues towards Eisenman’s more recent works struggling with the election of Donald Trump in 2016, then engaging with the Black Lives Matter movement after the police killing of George Floyd in 2020, thus missing the opportunity to frame these political commitments as coalitional and in dialogue with a specific history of Jewish involvement in the American Civil Rights movement.

Running at Whitechapel Gallery concurrently to ‘What Happened’ is ‘Speak, Poetess: an archival exhibition of artwork and writings by the British Jewish poet and artist Anna Mendelssohn’. As with Eisenman’s show, the accompanying text correctly identifies her political commitment to opposing fascism, patriarchy, the state and carceral logic in all its forms. What it fails to acknowledge is how much of her work was explicitly focused on her navigation of these oppressive forces as a Jewish woman and mother. Mendelssohn was born in 1948, three years after the end of the Second World War and ten years after an infamous Daily Mail headline declared ‘German Jews pouring into this country’ and warned of ‘aliens’ entering though the ‘back door’. Antisemitism is a constant opponent in Mendelssohn’s world, and she is an ambivalent inheritor of the Western intellectual tradition, explicitly grappling with the fascism of key figures such as Ezra Pound and Martin Heidegger. The press release highlights her ‘fascination with written languages that tend towards the ‘graphic and pictorial such as Arabic and Chinese’, assuming a preoccupation with impenetrability and leaving unacknowledged the fact that she had grown up with such a language in the form of Hebrew.

An untitled Mendelssohn drawing in ‘Speak, Poetess’ features a piece of machinery alongside the phrase ‘we are either in the lap of history or not’, and the conclusion of both shows seems to be, bizarrely, that we are not. This is especially ironic given the gallery’s location in Whitechapel, a historical centre of left-wing antifascist Jewish political organising, from the 1936 Battle of Cable Street to the Yiddish anarchist newspaper Arbeter Fraint (The Worker’s Friend), eminently relevant to the unacknowledged thread running through both shows. There is a missed opportunity to understand both Eisenman and Mendelssohn in the tradition of avant-garde aesthetics and radical-left politics as expressions of Jewishness for 20th-century secular Jews, post-Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment). In a moment where contemporary art discourse is often dominated by identity-driven interpretation, the difficulty of understanding Jewishness within contemporary categories of identity means that it remains invisible. However, it is precisely this diasporic ambivalence which is its unique contribution, recognising that rather than representation for its own sake, what is at stake is our ability to recognise epistemologies and ethics outside of hegemonic white Christian cultural assumptions. This is important, not just for the sake of asserting the centrality of Jewish contributions to a radical intellectual, political and artistic tradition, but also in affirming the continuing contribution of a radical, diasporic outlook to Jewishness. To return to the words of Daniel Kahn: ‘Babylon is everywhere and Zion is in you, so learn to take it with you – learn to be a Jew.’

Caspar Heinemann is an artist and writer based in Glasgow.

First published in Art Monthly 472: Dec-Jan 23-24.