Feature

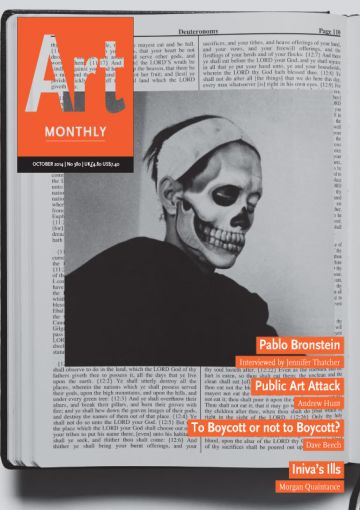

Public Art Attack

Andrew Hunt on the importance of antagonism in public art

Recent critical acts by artists, activists and graphic designers in the UK – among them Bill Drummond’s defacement of a UKIP poster in Birmingham, Mike Nelson’s troubled project for the Heygate Estate in London’s Elephant and Castle, Scott King’s absurdist proposal to re-invade and regenerate Afghanistan with gigantic sculptures made by Anish Kapoor and Antony Gormley, and even the supermarket chain Morrisons’ ambush of Gormley’s Angel of the North – suggest hostilities in culture or symptoms of discontent surrounding high-profile publicly funded artworks.

King’s project, Anish & Antony Take Afghanistan, for example – which initially took place as the exhibition ‘Totem Motif’ at Wolfgang Tillmans’ gallery Between Bridges in Berlin in May and June (the invitation card pictured two young women staring up in awe at a tall modernist sculpture by Henry Moore) and subsequently published as a small book by JRP-Ringier – runs with issues of power, taste and local pride via a fantasy narrative on a global scale connected to national ambition, war and cultural imperialism. Taking the form of a Victor-style comic, the project imagines an urgent United Nations invitation to Gormley and Kapoor (‘two giants of British public art’) to solve the financial and political problems of Afghanistan by invading the country and erecting massive sculptures. (‘Oh fiddlesticks, it’s that desk-wallah from Downing Street, I do hope it’s not another commission “oop north”,’ carps Gormley in King’s cartoon as the invitation arrives from Downing Street, while he and Kapoor sit smoking cigars in a Mayfair club.)

Apart from ridiculing the UK sculptural elite’s unquenchable hankering for ever-larger monuments under the guise of connecting with the communities of specific locales, such as Gormley’s Angel, 1998, and Kapoor’s Tees Valley Giants, 2008-, King’s imagined re-invasion of Afghanistan in 2014 to solve the damage done by NATO forces in the country since 2001, through ‘art’ rather than ‘war’, becomes a metaphor for the history of change in the north-east of England from the early 1980s to the present day. UN think-tank language is deployed to construct a resolution for a decimated world region, and culture is shown as a parallel ‘Band-Aid solution’ to cover up the crimes of impoverishment enacted by Margaret Thatcher on the communities in the UK through the destruction of industry and the commissioning of spectacularly tall ‘cod-avant-garde artworks’.

King’s recent works are a theatrical camping-up of public art and end-game capitalism in the self-conscious and highly debunked style of a late-Situationist cartoon, a device that admits its own unfeasibility by reference to the historical failure of the Situationist International in the early 1970s and the defeat of the British left in the mid 1980s. Yet this fabrication allows us to examine the lasting effects of public art during a period in which public money for art is gradually disappearing. King’s concept of ‘de-regeneration’ has previously allowed for an emotive deconstruction of regeneration through the proposal of alternative monuments to Kapoor’s corporate ArcelorMittal Orbit in Stratford which, if the myth is true, was agreed after a chance meeting between Boris Johnson and the steel billionaire Lakshmi Mittal in a toilet, rendering explicit the sometimes Stalinesque nature of decision-making around public commissions at big business and government level.

In keeping with King’s critique is the recent attack on Angel by supermarket chain Morrisons, which during early May projected a photograph of one of its large French sticks onto the sculpture’s wingspan at night, complete with the strapline ‘I’m cheaper at Morrisons’. The supermarket’s attempt to make its brand synonymous with Gormley’s icon through ‘ambush advertising’ unwittingly tapped into a critical perspective on class and regeneration. If one result of building new galleries and commissioning public art is the creation of bourgeois quarters that contain expensive independent shops, then in a reverse twist the budget supermarket’s temporary projection highlighted issues around inequality, through another Möbius strip of détournement and recuperation, to use antiquated Situationist terminology, in which the emancipatory quality of art was revealed as frighteningly ineffectual by a corporation’s actions.

Gormley himself was angered by the unsanctioned projection, which in his view made a mockery of the local miners and out-of-work shipbuilders from the Swan Hunter yard, the latter having been employed to produce Angel. He told Radio 4 on 6 May: ‘I was the instigator of a totemic object … on the site of the Lower Team Colliery, where people had worked for nearly a quarter of a century underground. It doesn’t belong to me, it belongs to the North East, and to see it trivialised like that was shocking and stupid.’ Comedian Stewart Lee weighed in on the subject with his sarcastic piece in the Observer on 11 May: ‘The stick of bread was the perfect shape to occupy the Angel’s wingspan, and one wonders what other products Morrisons might have filled Gormley’s emotionally resonant secular sacred space with next. A toilet brush perhaps? Or maybe a vibrating anal probe? Except that Morrisons don’t sell vibrating anal probes. They have standards.’ Lee’s humour dissipates quite quickly to reveal a sombre tone. ‘I do not believe in God,’ he wrote, ‘but the image of the Angel of the North moves me, as do the relics of our distant spiritual heritage strewn randomly around the British landscape.’ His thoughts are understandable after the recent relentless attacks on funding for culture. However, again the basic idea of good public art and barbarous corporations ignores certain political intricacies surrounding contemporary discourse, and he reveals a sinister perspective when he goes on to describe how Gormley won over the sceptical North East in ‘the battle for hearts and minds’ in the early 2000s, a comment that uses the very same language used both in King’s cartoon and by British politicians when describing soldiers winning a psychological battle over civilians in war zones such as Afghanistan. Moreover, Gormley’s notion that Angel belongs to the community in the North East rather than himself is paradoxically narcissistic. By insinuating that his sculpture is now a natural part of the environment – an equivalent to collectively produced ancient British earthworks – his attempt at self-deprecation by removing his singular authorship can be read as a marketing spiel intended to canonise his practice further. It is in his interests to keep the fallacy that Angel somehow made itself from the memory of the mining and shipbuilding community going, because the alternative would be to take responsibility for his egotistical invasion of the British landscape.

Previous examples of ‘ambush advertising’, such as Paddy Power’s act of drawing a jockey on the ancient Uffington Horse near Newbury racetrack in 2012, reveal an emerging tradition around the celebration of British monuments through corporate détournement, an act that was similarly damned by the puritanical Lee: ‘In March 2012,’ he writes, ‘the stupid bookmakers Paddy Power celebrated the Cheltenham horse murdering festival by drawing a jockey overnight on to the 3,000-year-old chalky flanks of White Horse of Uffington. Paddy Power claim to have done no damage and instead their own blog invited us to think of them as “lovable scamps” and “mischief makers”, the Horrid Henrys of wilful cultural vandalism.’

In opposition to this turgid moral superiority, I’d argue that the bookmakers’ temporary intervention on the Uffington Horse (which incidentally caused no damage) and its second stunt that positioned an inflatable horse as if hurdling one of Stonehenge’s standing stones in 2012, have an incongruous yet smart correlation with Land Art that echoes an entropic oscillation between the ancient, the modern and the contemporary, as well as inextricable links with works such as Jeremy Deller’s Sacrilege, the life-size inflatable replica of Stonehenge that famously toured the UK in the same year. Of course, Paddy Power’s latter stunt couldn’t have existed without Deller’s artwork in the first place as it was an obvious tribute, and in many respects Sacrilege’s UK tour’s ridiculous dérive, much like Paddy Power’s stunts, was positioned in opposition to Angel’s permanence, longevity and legacy so as to undermine and honour simultaneously the reverential and fixed ideas of heritage.

Either way, there are many parallels between the two artists. As a proponent of popular culture, and a fan of extreme fashion’s relation to extreme politics, King’s Anish & Antony seeks to level the cultural pecking order in a similar way to Deller, to give Angel the same importance as Blackpool Tower; both are spectacular monuments, cultural ‘stuff’ to put on the agenda in the use of new ideas. Interestingly, Gormley’s new corporate work for the Beaumont Hotel in London’s Mayfair, which was also launched in mid June, presents us with a similar shift from strict ideas of the sacrosanct public ‘regenerated’ space to the ‘corrupt’ and spectacularly private area, this time within the context of a luxury West End hotel room, a fact that is coincidentally mirrored in King’s cartoon (Gormley and Kapoor are shown in a private Mayfair gentlemen’s club) and indicates how Gormley’s work may continue to exist in ever more compromised ways with public funding in short supply.

Other recent activities involving advertising and guerrilla tactics appeared in Birmingham, again during May. Bill Drummond’s act of painting over a UKIP billboard poster with his own ‘Drummond’s International Grey’ – a new paint colour produced commercially for the public to buy in order that they might ‘vandalise’ anything they found ‘morally or aesthetically offensive’ – was part of his residency at Eastside Projects (Reviews AM377) and, uncannily, a second critique of a UKIP notice came in the same period attributed to the hotel chain Premier Inn. The Birmingham-born comedian Lenny Henry had been criticised in a racist tweet by UKIP candidate William Henwood, and Henry, who advertises Premier Inn, appeared to surpass himself in collaboration with the hoteliers in producing a billboard that showed the comedian reclining on a bed with the strapline ‘You Kip from only £25’. It transpired that in reality this was an elaborate hoax, a Photoshopped artwork that went viral on social media.

Perhaps if there is another loop of artistic, corporate and political antagonism in these actions between Drummond, Eastside Projects, Premier Inn and UKIP, it is that they are all master marketeers. Drummond’s visibility comes through his knowledge of media, via the history of his activities with the acid-house band the KLF, back to his original training as a painter. Eastside Projects has, for its part, developed an aggressive marketing campaign as a strategic curatorial art form in its own right, partly through its repeated use of billboard sites that make art public through a visibly political profile in the fabric of the city. At the same time, UKIP has exploited through its own high-profile anti-immigration billboard campaign the supposed lack of sympathy of the uneducated with official culture.

It is quite easy to see Mike Nelson’s recently cancelled Artangel project for the Heygate housing estate in Elephant and Castle, in which the artist planned to build a pyramid from the demolished modernist structure’s debris (Artnotes AM373), as an antagonistic public artwork par excellence. In the face of mounting criticism, and with local elections looming on the horizon, Southwark Council cut Nelson’s project the week before Christmas 2013. An online article called ‘Pyramid Dead’ by Christopher Jones of the political sound art group Ultra-red, which was published by Mute, was critical of Artangel and Nelson, while another young London-based curator posted a humorous message on Twitter in May – ‘it’s interesting to see that Nelson’s gone Kate Moss mute on this subject’ – after Jones’s article started circulating, with the artist’s silence being misread as an admission of his collusion with the ‘enemy’.

Anger towards the council is justified: it had ordered the demolition of the estate because it wanted to attract a ‘better class of people’ to live in the area and because many of the former residents were not relocated in Southwark. Peter John, the council’s leader, and its chief executive, Eleanor Kelly, were also responsible for selling the estate’s land to the multinational property company Lend Lease for too little money, undercutting public assets in favour of private ownership. However, despite these obvious attempts at social cleansing, I’d argue that Nelson’s decision to accept the invitation to produce a public work on the Heygate site was made in order to reflect urgent political issues and to engage in a favourable dialogue with campaigners’ concerns.

In the face of such opposition, it is initially important to situate Nelson’s proposal in a wider art-historical context connected to gentrification, such as Gordon Matta-Clark’s building cuts of the early 1970s and Mike Kelley’s Mobile Homestead from 2013. Matta-Clark’s ‘anarchitecture’ called for a process of de-structuring and focused on existing edifices in neglected areas, while Kelley’s full-scale replica of the 1950s Westland suburban Detroit home he grew up in was produced and relocated to the city centre in a provocative reversal of the ‘white flight’ that followed the uprisings known as the 12th Street riot in 1967. Kelley’s was a challenge to a city decimated by economic change, and it was his view that ‘one always has to hide one’s true desires and beliefs behind a facade of socially acceptable lies’ to produce a confrontational work.

Leading on from this, Nelson’s pyramid advocated a hostile dimension simply through its singular aesthetic form, something that was provocative because it appears less didactic and stylistically sensitive than traditional socially engaged practices, and non-confrontational compared to antagonistic variations on a relational theme. In terms of the latter approach, Santiago Sierra’s work with communities, for example, is always clear about its ‘monstrous’ acts of exploitation of those that participate in his work – his cards are always on the table, so to speak. Nelson’s practical and aesthetic disinterest didn’t pretend to have any direct social connection with the displaced Heygate estate’s community, in opposition to Gormley’s attempted empathy with the communities of the North East. In this sense, we can see a development of Claire Bishop’s reply to relational theories a decade ago, which argued for radically disjunctive antagonistic forms of socially engaged art.

Nelson has said that, in his view, what has happened to the Heygate is so ruthless that ‘an artwork was needed that represented the same form of brutality’. In aesthetic and symbolic terms, the highly coded ancient form of the pyramid, which the local authority and local activists found hard to decipher, is perhaps a perfectly pitiless form because it contains conspiratorial connotations and links to occult literature, not least the famous paranoiac Jordan Maxwell’s discussion of the US dollar bill’s Illuminati pyramid linking it to secret societies, which Nelson referenced in his earlier work, Triple Bluff Canyon, 2004 (Interview AM278). Through this, Nelson’s work would have become a hallucinatory cogitation on Southwark Council’s manipulation of the local community. Unfortunately for all involved, local activists’ misreading of Nelson’s project as siding with gentrification and displacement was seized upon by Southwark Council as a reason to cancel the commission, effectively gagging local activists’ arguments, deflecting criticism away from the council and making a scapegoat of the artist and Artangel.

Apart from drawing reference to the Greek wars via the campaigners’ Pyrrhic victory, another feature of Nelson’s work is contained in its working title, Low Rise, an obvious reversal of JG Ballard’s horrific novel High Rise, 1975, in which a tower block’s residents lock themselves inside an increasingly brutal internal system of class war: life degenerates as minor power failures and petty annoyances among neighbours escalate into an orgy of violence. Outside this dystopian context, the cancelled Heygate work can be seen as a rereading of Hal Foster’s theory of the ‘pre-post-erous’ in ‘An Archival Impulse’, 2004, as well as his essay on Deller for the 2013 Venice Biennale. This idea tackles a future-oriented view of history – in terms of a ‘pre’ (the past) and a ‘post’ (the future) – that aims at a view of a society to come from the present moment. Like Robert Smithson, who Ballard famously worked with and whose entire project was cut short early through his death aged 35 in 1973, I would argue that Nelson’s unrealised work had the potential to open on to a different sense of time: beyond geological time and on to a heterogeneous temporality that is different to the inexorable father-time of capitalism.

Not only would Low Rise have produced an interesting breach of the discourse of social housing and exclusion through entropy, it would have attempted a temporary transition from the ancient to Modernism, through Postmodernism, and on to what exists now and beyond. This connection with Smithson’s concern for redevelopment and the erasure of history – issues addressed also in Thomas Crow’s writing on Rachel Whiteread’s House – are much like Matta-Clark’s interventions, which worked because they formed a temporary breach rather than a permanent memorial to a lost community.

What is important in all of these projects is that they attempt to challenge the dominant discourse by acting as perverse methods that disturb the symbolic order at large. Although Nelson’s cancelled project, like those of King and Drummond, exists within a paranoid dimension of antagonistic public art, it shows a surprising desire to turn belatedness into becomingness, or transform everyday life into possible scenarios of alternative social relations.

Andrew Hunt is a curator and writer.

First published in Art Monthly 380: October 2014.