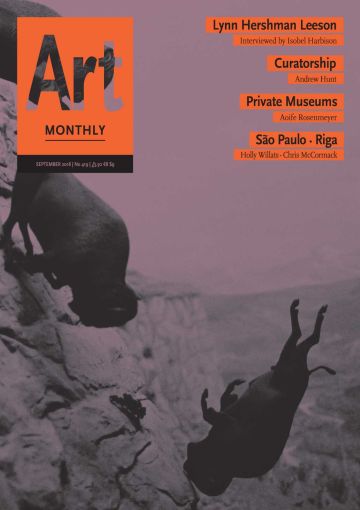

Report

Private Museums

Aoife Rosenmeyer on the current boom in private art institutions

Private museums are no novelty and make up a highly varied field. Recent exhibitions such as the Fondazione Prada’s recreation of ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ in Venice in 2013 or the Schaulager’s 2018 Bruce Nauman spectacular in Basel demonstrate how their private resources can be excellently spent. In several European countries and in the US, collectors with foundations enjoy significant tax breaks and other state support in exchange for sometimes limited public access. In Paris, for example, the Fondation Louis Vuitton is built on public land on condition that the building becomes state property in 55 years. Beyond Europe and the US, where private funding has long been a mainstay of the cultural sector, interesting examples are David Walsh’s ambitious MONA (‘Letter from New Zealand’, AM410), which brings art pilgrims to Tasmania, or the Instituto Inhotim in Brazil (whose founder Bernardo Paz was inconveniently convicted of money-laundering and tax evasion in 2017, not to mention the accusations reported by Bloomberg and other news sources that he has used child labour and infringed environmental laws).

In Switzerland, the art scene is all the richer for countless private establishments, such as the aforementioned Schaulager, the Tinguely Museum, Fondation Beyeler, Maja Hoffmann’s LUMA foundation, which has a foot in Zurich as well as its monumental new campus in Arles, and many smaller centres.

The 3rd ‘Private Museums Conference’ on 14 June, during Art Basel fair week, was not a critical forum but a space for a rare and privileged species to congregate. Nonetheless, it shed significant light on the opportunities and stresses the current boom in private art institutions generates.

Opening, Cristina Bechtler underlined that the conference sought to establish ‘best practice’ in the sector; Bechtler’s EAT foundation initiated the free event. Moderator Emily Scott briefly considered how the private museum has developed from the gentleman’s Wunderkammer to hybrid contemporary forms like Hauser & Wirth’s LA gallery, where helpful guides, cafe and shop all give a museum feel (Bruno Bischofsberger’s gallery outside Zurich has a similar ambience). Private wealth is bringing about the contrasting trends of what Hito Steyerl calls ‘duty free art’ hidden from view in storage facilities and brash platforms open to the public. Jens Faurschou then presented his foundation’s activities in Copenhagen, Beijing and New York; his talk, entitled ‘Sustainability in the World of Art. The Economic Ecosystem Around the Masters’, sketchily explained how profits made on the secondary market were put to buying and producing new works. A ripple of approval went around the room when he showed Richard Mosse’s Incoming 2014-17, which he had snapped up at the fair earlier that week (Reviews AM405; Letters AM406, AM407). Next, Ziba Ardalan, who founded and runs Parasol unit in London, reviewed the history of private museums – which she dated back 2,500 years, though without substantiation – stating that private museums are now in the majority in the UK and in several other countries. (A challenge to analysis of the sector is that the distinction between private and public institutions is unclear; the exhibition programme at Parasol unit, for example, has been supported by Arts Council England and Tower Hamlets Council. Ardalan equally cited the acquisition of a significant body of Alberto Giacometti’s work for the Kunsthaus Zurich, the oldest ‘Kunstverein’ still in existence which receives generous support from its city and canton, as an example of a private initiative.) Speaking specifically about Parasol unit, Ardalan promoted its Kunsthalle-like model of operating, mounting only temporary exhibitions. She is, she said, unconcerned about legacy or heritage, but engaged in ‘giving something back’.

Headline act Chris Dercon then updated his afterword to Bechtler and Dora Imhof’s collection of interviews with museum owners, The Private Museum of the Future, published by JRP Ringier and being launched at the conference. Riffing on parallels between Indiana Jones and Damien Hirst’s 2017 show at the Pinault collection in Venice, Dercon told a story of private museums and collections in terms of ruins and what is left behind. Critique thus blunted by humour, he identified the high-gloss sameness of numerous private collections and collectors’ short-term thinking as well as their positive aspects. Private buyers can purchase at speed, do so in areas where public institutions are outpriced and may fill holes in myopic cultural accounts. He admitted that, thanks to the power of private finance, many public institutions are already guided by private individuals’ interests. Closing, he spoke for new museum models for performative, temporary and other art forms, and admitted that his tenure at the Volksbühne in Berlin had been a failed attempt to achieve this; listeners may have been wondering if this is a project he could pull off in the private sector.

Architect Adam Caruso completed the line-up, discussing Caruso St John museum projects with Phillip Ursprung of the ETH school of architecture, among them Nottingham Contemporary and Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery. These clients brought distinctive briefs and priorities – every storey of Hirst’s building could support his heaviest (did he really say 72-tonne?) piece, for example. And, finally, Caruso shed some instructive light on the financial realities currently besetting public institutions that soldier on regardless: ticketed blockbuster exhibitions have become a necessity where access to permanent exhibitions is free; museum extension projects are dangled as sponsorship-opportunity carrots in front of donors uninterested in funding operational costs; and, of course, the arts are an easy target for government spending cuts.

Though Dercon’s published text does consider how public and private institutions might work together, neither Ardalan nor Faurschou were interested in responding to the question – it remained the elephant in the room. How can public institutions win if they enjoy neither the resources nor the flexibility of private institutions, yet they carry huge responsibilities for long-term, catholic cultural production, recording and preservation? No matter how munificent a collector is, private museums are selfish projects driven by personal interests and whims. Could public art institutions do more to engage them as donors? Perhaps, but few governments, and certainly not the UK government, seem willing to stand up for the public sector, especially if they feel relieved of their cultural responsibilities by private museums whose high-net-worth owners they are keen to cosy up to anyway. Worse still, there is a danger that states will end up stepping in to save failing private foundations when their founders’ interest or funding runs out. Are we sleepwalking into a scenario where cultural property purchased with dubious wealth is further whitewashed by states? Maybe some private museum owners will be brave enough to enter into a discussion about best practice in public-private institutional collaboration – though Bernardo Paz probably won’t be available.

Aoife Rosenmeyer is a critic and translator based in Zurich.

First published in Art Monthly 419: September 2018.