Feature

Plant Matters

Michaële Cutaya on the politics of plants

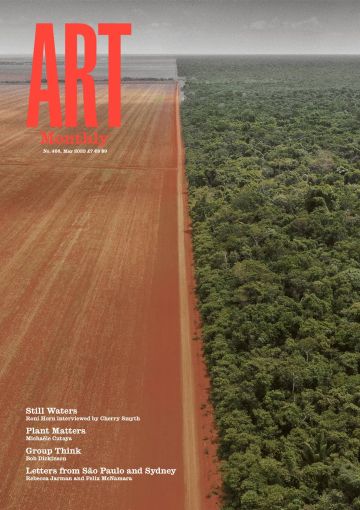

Herbie McCann installing Christine Mackey’s Mesocosm on Blackrock Lake, 2022

Here is a paradox: on the one hand, plants are everywhere, even down to the paper you might be reading this on; but on the other hand, they are disappearing. Plants are, however, enjoying what may be called a vegetal turn. Hardly a day goes by without some news item about crops failing due to extreme weather events or the need to explore and research species’ adaptability to changing climatic conditions. Trees take the spotlight, but wild flowers are also having a moment, as food for pollinators and in their own right. We see all this reflected in the number of books on display in bookshops, whether they are field books, stories of rewilding, garden books, plant philosophy, plant medicine and so on. Gardens, public and private, are being reinvented everywhere. Countries such as Ecuador, New Zealand and Germany are giving plants constitutional rights. In academia, post-humanist studies are turning to plants, giving rise to such terms as ‘critical plant science’ or ‘radical botany’. There are philosophical and political considerations of the potential of plants’ ontological being as a model of political resistance and a proposal that we are in fact living in the Planthroposcene or in a nation of plants. Plants are also having something of a revival in films – if still within the sci-fi horror genre. Yet plants are disappearing, quite literally so, as the recent publication of the Plant Atlas 2020 by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland reminded us: the 20-year study documented that half of our native flora is in decline. More broadly speaking, 40% of plant species worldwide are threatened with extinction.

Plants are also disappearing from the educational system, as the subject of scientific research and plant literacy has plunged to a new low in the general population. In 2015, 28 authors wrote against the decision by the Oxford Junior Dictionary editors to cut around 50 words connected with nature from the 10,000 definitions aimed at seven year olds. Words such as ‘acorn’, ‘crocus’ and ‘clover’ were replaced with the likes of ‘broadband’, ‘attachment’ or the term ‘cut and paste’. The head of children’s dictionaries at OUP said the dictionary followed the changes in children’s environments: ‘When you look back at older versions of dictionaries, there were lots of examples of flowers for instance. That was because many children lived in semi-rural environments and saw the seasons. Nowadays, the environment has changed.’

This is a good example of the negative feedback loops identified by the authors of an article published by Ecology and Evolution in July 2022, ‘The botanical education extinction and the fall of plant awareness’. ‘At its core,’ the authors argue, ‘the extinction of botanical education is comprised of two simple interacting cycles: the fall in plant awareness through a lack of exposure to plants and a loss of knowledge through a diminished demand and provision of botanical education.’ Not for the first time did scientists warn against what was termed ‘plant blindness’ in 1999 and the continued decline of botanical knowledge in universities and education more generally. Of particular concern is the loss of identification skills due to the continuing lack of interest in taxonomy and systematics.

Whether they are a laboratory for the future, or a place of last refuge, it seems that the arts abound with plant awareness. Of course, plants and artists go back a long way. Botanical knowledge owes much to artists and their ability to capture the specificity of a specimen ever since Theophrastus and Dioscorides, and there were times when the distinction between artists and scientists was rather blurred, making it difficult – and rather pointless – to decide whether, say, Albrecht Dürer’s paintings and drawings of plants are botanical plates or works of art.

Closer to us, it seems that plants have not enjoyed such attention since their heyday in the 1970s. The past ten years or so have seen several events engaging with plants in one way or another. To list a few: starting in 2020 and continuing to tour is ‘Plant Fever’, a European travelling exhibition conceived as ‘an invitation to look at plants with renewed curiosity and discover their hidden potential’; the exhibition ‘The Botanical Mind’ at Camden Art Centre in 2020–21, which engaged with ‘various cultures and wisdom-traditions to reappraise the importance of plants to life on this planet’; in 2019 at the Serpentine Gallery there was a day-long symposium in the series ‘The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish’ that was ‘dedicated to the latest research in the intelligence of plants, and in the ancient and profound knowledges and interactions that humans, plants and other species have had’. Among the speakers at the Serpentine were Natasha Myers, who discussed her idea for a Planthroposcene (a term she coined in 2016 as a way to move beyong the Anthropocene by signalling an acceptance that humans are of plants), and Michael Marder, author of Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life, 2013.

Likewise, individual artists are exploring relationships with plants in their practice in all kinds of ways. Carsten Höller, for The Florence Experiment, 2018, in collaboration with plant neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso, installed two signature intertwined tube slides going through the Palazzo Strozzi. Visitors were invited to slide down holding a bean plant, which was subsequently tested to see if the emotions had translated into a photosynthetic reaction, giving a serious consideration to ideas more often associated with 1970s counterculture. In another genre, Zheng Bo, for his video Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvärkstallen), 2022, presented at the recent Venice Biennale, shows men engaging in sexual relationships with plants in a wood.

It is perhaps the idea of the garden that stands out particularly, however – a garden invested with a strong political and transformative potential. In his 2016 book Decolonising Nature, Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology, TJ Demos reviewed the case of Documenta 13 in a chapter titled ‘Gardening Against the Apocalypse’. Demos made the case that ‘overgrown with experimental planters, creative landscapes, and installations relating variously to horticulture, farming and natural life-forms’, Documenta made an ‘implicit linkage of gardening and political emergency’. Among the many models of garden-as-art created for the show, Demos mentioned Kristina Buch’s The lover and Song Dong’s Doing Nothing Garden.

To those who might think that gardens are irrelevant, Demos objected that they responded to ‘the most urgent of global conflicts’. These were: ‘the financialisation of nature by agricultural and pharmaceutical corporations enforcing use of their patented genetically modified seeds; greenhouse gas emissions from a monoculture and export-based agribusiness reliant on chemical fertilisers and fossil-fuelled transportation industries; and the destruction of unions and small-scale farms displaced by large-scale mechanised agricultural productions’.

For its 12th iteration in 2018, Manifesta was sited in the botanical gardens of Palermo (Reviews AM421). Titled ‘The Planetary Garden’, it set out to look at the idea of the ‘garden’ in ‘its capacity to aggregate difference and to compose life out of movement and migration’. For all the beauty of the place, there was a strong political content there, too. The planetary garden is a concept borrowed from French landscape designer or philosopher gardener Gilles Clément. Over his many years of practice, Clément has developed a number of concepts that are really changing the way we think about gardening. As a landscape designer he immediately moved away from the dominant architectural conception of the profession and began a life-long love affair with weeds, which he called vagabonds. They inspired his idea of the garden in movement, which he explored in his 1991 book Le Jardin en Mouvement, and in which he explained how he made space for the unwanted and worked with the unexpected.

Clément’s 2002 book In Praise of Vagabonds – Herbs, trees and flowers to conquer the world opens with: ‘Plants travel. Especially grasses. They move about as quietly as the wind. We can’t do much about the wind.’ Further, Clément asks: ‘how can we maintain the landscape, and manage its expenses, if it is transformed at the whim of hurricanes?’ The bulk of the book tells the story of some of the most hated, mostly alien species, often officially outlawed and designated for eradication, such as giant hogweed, gorse, butterfly-bush or Japanese knotweed. Arguing against these attempts at regulating life, he sees quite a few parallels between nationalistic rhetoric and (some) ecological discourses: ‘Such a project – security at all costs – finds unlikely company among the ecological radicals, keepers of nostalgia. Nothing should change, our past depends on it, say the ones; nothing should change, diversity depends on it, say the others. Everyone rails against the vagabonds.’

Now there are spontaneous affinities between weeds and artists: weeds are ‘useless’, they are ‘unwanted’, they grow in unexpected places, they disturb the established order. What’s not to like? To stay with Dürer, perhaps his most famous painting of plants is The Great Piece of Turf, 1503, which portrays various grasses, dandelions and plantain to form a joyous riot.

One artist who has often been associated with the ideas of Clément is the Austrian Lois Weinberger. He worked on his ‘garden archive’ from the 1980s – he calls it ‘the area’ – long before presenting his work at international events. In this area he has cultivated weeds, collected throughout Central and Eastern Europe, to serve as a reservoir for some of these endangered species. When Joseph Beuys was bringing the noble oak to Kassel for Documenta 7 in 1982 (7000 Oaks), Weinberger brought the humbler but also possibly more subversive seeds from his collection. In 1997, for Documenta X, Weinberger planted the seeds of ruderal plants on a decommissioned section of railway tracks of Kassel Central Station for the multi-year project What is Beyond Plants is at One with Them. The project is continuing. The work plays on the idea of the Third Landscape, which Clément describes as neither reservation nor productive, but spaces of human activity that have been abandoned and left to their own devices, whether in cities or in rural areas. He sees each such space as ‘a special place of biological intelligence’, with an ‘aptitude for constant reinvention’.

Another evocative series of works by Weinberger are his ‘Portable Gardens’, begun in 1994. They take the form of carrier bags or plastic containers filled with earth and ruderals that can be easily transported, each forming its very own micro ecosystem, such as the ones that spontaneously spring up every time we leave a container unattended – a bucketful of local knowledge.

The work of the recently departed Weinberger was influential in the development of Leitrim-based artist Christine Mackey’s practice. She began collecting seeds with RIVERwork(s) in 2006, a public commission to explore the landscape and history of Doorly Park in County Sligo. The three-month residency led her to explore all aspects of the place, and that is when she began working with seeds. She researched both those she collected in the landscape and extinct varieties in historical botanical catalogues. She sees seeds as ‘tiny but powerful tools for environmental change’. Like Michel Foucault’s patient and meticulous genealogist, she is less interested in a single point of origin than in the unexpected and accidental, such as when she tracks the journeys of the Daniel O’Rourke pea from Kilkenny to Clare via the UK, the US, Iraq and Russia in order to erect a monument to its uncelebrated importance (The Pea Archive, 2013) or recounts in a short publication the peregrinations from India to worldwide domination of the abhorred Himalayan Balsam (Balsam Bashing, 2014). As an environmental activist, she occasionally trespasses on private properties to replant apple trees, as in the 2013 work PIP.

Over the years, Mackey’s practice has woven together fieldwork, philosophical discourses, exhibition-making and, recently, actual willow shoots. Weaving baskets is a skill she acquired for her latest project, Mesocosm. ‘I began to think about the garden as a floating island’, the artist recounts, ‘and started to do some basic research on the history of floating islands and gardens and also how artists have contemporised these forms anew.’

Mesocosm – medium world – is a scientific term designating a partially enclosed outdoor experiment, halfway between laboratory conditions of experimentation and the real world. Mackey explains that she found the term useful as it allowed her ‘to set the project up as an experimental ecosystem closest to the real world that has the capacity to change and adapt according to the material conditions of the landscape, the site and its embodied structure’. Mackey constructed small floating islands in the form of large willow baskets in which she arranged seeds collected from diverse geographical areas. The yellow flag irises, purple loosestrife, marsh woundwort, marsh marigold and water mint, amongst others, were chosen for their adaptability and their phytoremediation capacities.

As one of her references, she mentions Mel Chin’s Revival Field, 1991, an installation of what she calls ‘Hyperaccumulator’ plants in a fenced-off area at Pig’s Eye Landfill in St Paul, Minnesota: in the successful experiment, the plants extracted heavy metals from the soil before being harvested and burnt to recover and recycle the metals. Similarly, the floating gardens of Mesocosm have the practical function of floating wetlands, but to make sure that (unlike existing models made of polyethylene and polyvinyl foam that eventually leak pollutants) they will break down without causing distress to the hosting system, a number of practical challenges presented themselves. The weaving of willow branches into large baskets solved one problem. To solve the issue of buoyancy she turned to mycelium, a network of fungal threads that grows underground which she baked in moulds and attached to the islands to stabilise them.

But these worlds in the middle are not just remedial, they are a proposal for experimental combinations of elements, plants, animals, bacteria. The islands serve as shelter for animal and vegetal life alike. Mackey released some of her floating gardens in Blackrock Pond at Drumshanbo in County Leitrim during summer 2022 as part of the Eco Showboat programme. In an overhead shot of the pond, we see a man sitting in a large boat-like basket to which a flotilla of basket gardens is tied. The sunlight plays on the ripples going from one to the others making the circular shapes resonate with the water surface. As Gilles Deleuze insisted, we can only ever begin in the middle.

It is only a few years since Siobhan McGibbon’s practice turned towards the garden, but the move was embraced enthusiastically and one might say monumentally. For her latest body of work, ‘Xenophon: Making Oddkin with Japanese Knotweed’, she continued to associate the unlikely materials that had characterised her art, and also to seek out alternative forms of being. Xenophon is the collaborative world she has been exploring with writer Maeve O’Lynn, whose inhabitants they describe as ‘a fluid species that commune and mutate with living and non-living entities to adapt to the Anthropocene’. The research has involved forays into multi-species studies that challenge the hierarchy of species. This came into her consideration in approaching her garden after moving back to West Cork a few years ago. The writings of Joe Crowdy became particularly important when she wondered what, if anything, she should do about the growth of Japanese knotweeds at the bottom of the garden. In the article ‘Queer Undergrowth: Weeds and Sexuality in the Architecture of the Garden’, Crowdy sums up how weeds have been described from the Bible, The Gardener’s Dictionary, 1735, to the Royal Horticultural Society’s Encyclopedia of Gardening: ‘As in Eden, every individual garden has its own moral economy where the horticulturalist plays god – policing the behaviour of various species through propagation and extermination, in order to create an image of paradise.’ In this paradise there is no place for weeds because they ‘show no respect for human norms of taste and private property’, ‘a weed is a threat to the garden’s spatial order’; furthermore, ‘the growth of a weed is obscenely vigorous: it grows “wild and rank”, displaying a rampant vitality quite shocking to civilised eyes’. The dreaded Japanese knotweed is a good instance of a weed’s resistance to human control not only in that it is ‘often impossible to eradicate fully’ but also that it ‘refuses to be cultivated’.

During a research residency at the Leitrim Sculpture Centre in 2020, McGibbon looked for ways of ‘living with’ the organism and began the ‘Making Oddkin with Japanese Knotweed’, body of work (in a nod to Donna Haraway), which was presented at the Galway Arts Centre earlier this year. She used various strategies for containing the growth without eradicating the plant, and found practical applications for its harvest, such as making jams, bread, tinctures, chutney, pickle and gin. But it is perhaps the hybrids the plants inspired that capture the imagination most: vividly coloured assemblages of man-made tools, organic and synthetic matters with such listed materials as ‘wheelbarrow, knotweed, soil, sculptural silk shibori, Japanese knotweed stalk, foxglove, dandelion dye, unreal clay’. The monumental Flipping Relations, 2022, presented casts of Gunnera Manicata more commonly known as giant rhubarb – a garden favourite that has become the scourge of various ecosystems. The moulds render in clay the intricate structure of the huge leaves but the flesh-coloured tones give them a charged erotic presence. Like the other exhibits, the leaves are covered with a type of synthetic modelling clay that is commonly used for animation because it remains malleable. This clay covers the hybrids like a skin, giving them bright, pastel colours and a soft surface seemingly offered to the next nudge of a modelling tool or that of a meddlesome thumb, still in the making. This somewhat captures a quality that Marder attributes to plant life: ‘Across its play and display, vegetal being does not diverge from appearance: the plant wears what it is on its sleeve, or, more accurately, on its leaf.’

Marder goes much further and for him plants are artists in their own right, the artists of being: ‘plants create and recreate themselves all the time, growing new limbs, shedding leaves, putting out new sexual organs … Vegetal self-creation and self-recreation takes its cues from the conditions outside without a rigidly predetermined organismic plan. The artistry of plants that make themselves is, therefore, of one piece with the world.’ He also proposes vegetal being as a model for political resistance and takes issue with a recent Disney animated film (Strange World, 2022), which he considers as nothing short of fascist in its promotion of organismic totality.

Perhaps that is taking it a step too far, but that plants may suggest a way of being to ponder was already a beautiful possibility in these words by Friedrich Schiller in his 27th Letter on Aesthetics, 1794, which are quoted by Marder: ‘Even in mindless nature there is revealed a luxury of powers and a laxity of determination which in that natural context might as well be called play. The tree puts forth innumerable buds which perish without developing, and stretches out for nourishment many more roots, branches and leaves than are used for the maintenance of itself and its species. What the tree returns from its lavish profusion unused and unenjoyed to the kingdom of the elements, the living creature may squander in joyous movements. So nature gives us even in her material realm a prelude to the infinite, and even here partly removes the chains which she casts away entirely in the realm of Form.’

Botany’s botanical gardens and herbaria have been tainted by their association with colonial empires; specimens were collected alongside the exploitation of indigenous peoples and the extraction of their resources. The plants of the world came to fill the newly devised botanical nomenclature of Carl Linnaeus. Such taxonomies are now routinely criticised as representing the imposition of a colonial and patriarchal order on the diversity of the living. Yet in Pisa in 1544, when Luca Ghini introduced his students to the study of actual plants instead of relying on their De Materia Medica, setting up the first botanical garden and preserving specimens between two sheets of paper for the first herbarium, the impulse was similar to that of the artists of a few decades earlier, who – emancipating themselves from their model books – went out to look at the world for themselves as the garden of Eden it always was. Famously, Dürer encouraged artists to ‘study nature diligently’. The early years of Humanism were exhilarating in their openness and curiosity, before turning into the reductive anthropocentrism we are attempting to move beyond. If contemporary artists are looking at plants anew, it may not be with the same contemplative attitude – the world is changing too fast to allow for such luxury. But they may look closely at the diversity of the plant world, to speculate on the future of our planetary garden. We need to know and recognise what is out there first.

Michaële Cutaya is a writer living in County Galway.

First published in Art Monthly 466: May 2023.