Report

Pissed Off

Henry Broome on homelessness, sanitation and public art

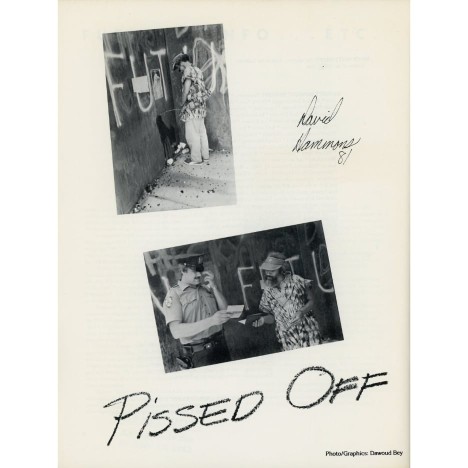

David Hammons, Pissed Off!, 1981, published in vol 2 issue 1 of Franklin Furnace’s magazine FULE, photos by Dawoud Bey

Visiting a city in Germany soon after New Year’s Day, my friend and I travelled to a nearby sculpture park located between the red-light district and the financial quarter, a zone shadowed by the towering, shiny blue glass of banking HQs, impenetrable to outside eyes. There was plenty of traditional public sculpture, including statues of famous historical figures – Friedrich Schiller, Ludwig van Beethoven – and reclining female nudes with water fountains springing from between their legs but, at the park’s edge, on the border with the ring road, we came across an uncanny structure, a black cylindrical shaft, four metres high and two metres in diameter. ‘Apparently, it is a public urinal designed by an artist,’ said my friend looking down at her phone.

The steel door was shut, no handle on the outside. Spotting a small gap at the top of the frame, my friend tried to prize it open with her fingertips but the door wouldn’t move. I could see a keyhole. ‘Maybe it’s locked,’ I said, getting cold. Determined not to give up, she kept trying. Suddenly, the door flung open. ‘Sorry!’, she screamed. A man was living inside, nestled around his belongings, the floor completely covered, up to his ankles with plastic bags, blankets and clothes. We apologised for the intrusion and, smiling at us forgivingly, he slowly closed the door from the inside.

Access to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights; it is a human right in itself – as formally recognised by the United Nations General Assembly in 2010 – yet unhoused people, including people sleeping rough in encampments or shelters, face extreme water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) insecurity. According to a paper published by the International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, open defecation and overuse of limited available WaSH facilities carry the risk of serious infection, including Hepatitis A, enteric infections, TB, MRSA and leptospirosis.

I only saw him for a split second and I don’t even think our eyes met, but for months I couldn’t stop thinking about the encounter. I wasn’t sure what I should do but I felt implicated, as though the experience required some response from me and that I had to address it – the indignity, the injustice of the man’s living situation. Still feeling unsettled, it wasn’t until a few months later, back home in London, that I searched for information about the installation. I found it on the state’s public art website. The work was commissioned by the city’s contemporary art museum with financial support from one of the banks headquartered on the park. The Google-translated description says it is ‘open to everyone’ 24/7, claiming not only to serve the employees of the surrounding banks but also the homeless people and drug addicts who seek refuge in the park, pushed out from other parts of the city.

I couldn’t see it at the time but, from pictures online, there is apparently a metal grate on the floor, a steel pan underneath, and tanks dug underground to collect the urine – the smell rises up from below, I imagine. There is no roof to keep the cold and wet out, no light for night-time use, no bin to safely dispose of needles as some public toilets have and, more fundamentally no hand-washing facilities, no soap, no water, no dryer, no seat, no toilet paper; there is just a hole in the ground, intentionally designed not to accommodate the full needs of homeless people, to specifically mitigate against anyone permanently sheltering in the structure.

In the UK, at least in London, it appears there are regulations that prohibit public art from providing shelter for the homeless, especially in urban environments. Speaking to BOMB Magazine in 2018 about a public sculpture he made for New York, artist Yinka Shonibare referred to the planning conditions around his 2014 Wind Sculpture that was to be installed on Howick Place close to London’s Victoria Station: ‘The city didn’t want homeless people to use the sculpture as shelter, although I didn’t mind,’ Shonibare said. ‘In order to abide with the city rules, I had to create a form that was dynamic enough with less curves.’

Public art is sometimes something like the spikes you see over heat vents, the armrests across the middle of benches, urine deflectors (see Tom Denman’s profile on Dora Budor in AM474), part of the hostile architecture, seen mostly in urban areas, designed to restrict homeless people’s access to public space and public WaSH facilities. In Brixton, where I live, there is a massive ‘pay-to-use’ public toilet, further exacerbating the area’s homelessness and drug addiction problem: ‘20p ENTRY’ reads one sign next to coin slots and contactless payment points; ‘No Alcohol, No Smoking, No Drugs’, reads another. Guys tend to piss up against the side of the building, streams of urine running into the street, day and night, never completely drying. I am reminded of David Hammons’s defiant 1981 performance Pissed Off, in which the artist urinated on Richard Serra’s TWU, three 12ft-wide steel plates looming 36ft high to form an imposing monolith on a tiny traffic triangle in NYC’s Tribeca area, now known as Finn Square. (The sculpture stood there from 24 April 1980 to 30 July 1981 and was named after the Transport Workers Union, whose members were on strike at the time; it is now permanently installed in Hamburg, Germany). ‘In New York City,’ Hammons explained, ‘a man doesn’t have any public access to relieve himself in a decent manner [...] without having to buy a drink. Keep the rage going.’ The artist and photographer Dawoud Bey took a series of photos of the performance. Hammons first appears standing inside the walls of Serra’s sculpture, cans piling up in the corners, broken glass on the floor, wheat-pasted posters and graffiti covering the walls. (If you piece the images together, you can make out the words ‘NO FUTURE’ spray-painted across the three plates.) Next, he pisses in the corner. Then we see Hammons talking to a cop; the artist is presenting some papers, perhaps his ID. Some descriptions of the photograph say he is being arrested or given a citation but this has not been verified by Hammons himself.

As noted by a policy brief from the Water Centre at King’s College London, states tend to punish people who are forced to urinate and defecate in the open rather than provide free-to-use public toilets across the areas where they are needed. Dr Jessie Speer observes that homeless populations are depicted as dirty and dangerous in public policy and their removal is often described as ‘cleaning up’ public space. Under the UK’s proposed Criminal Justice Bill, so-called ‘nuisance’ rough sleepers could be moved on, fined up to £2,500 or imprisoned (as if homeless people have that kind of cash at their disposal). The move to further criminalise homelessness comes after Suella Braverman, when home secretary, vowed to restrict homeless people using tents, infamously describing rough sleeping as a ‘lifestyle choice’. Writing on social media, Braverman said ‘we cannot allow our streets to be taken over by rows of tents occupied by people, many of them from abroad’.

There is definitely a link between notions of ‘cleanliness’ and ‘racial purity’ in right-wing discourse around public space and public art. In 2015, the MailOnline ran a story about ‘homeless Eastern Europeans’ camping at a Hyde Park memorial commemorating the victims of London’s 7/7 bombings. The memorial is made up of a plaque and 52 steel pillars, one for each person killed in a series of suicide attacks carried out by terrorists on 7 July 2005 (see Dave Beech’s ‘Inside Out’ in AM329). The MailOnline accused the group of ‘cluttering the memorial with their sleeping bags and suitcases’ and, despite providing no photographic evidence, claimed they had been seen ‘eating dinner off the plaque and even using the memorial site as a makeshift toilet’. Again referencing Eastern Europeans, three years later the London Evening Standard incited a moral panic about homeless people washing themselves and their clothes in a water fountain in Hyde Park. Dog owner Jason Broadhurst told the reporter: ‘They were even washing their underwear. We were all looking on in shock.’ Royal Parks, which manages the grounds, said that it drained the ‘Joy of Life’ fountain so it could be sanitised. For the right-wing press, racialised groups of unhoused people must be cleansed from public spaces, not permitted to access the joys of life; it is their will to survive which is so reviled.

How can the homeless go beyond just trying to stay alive? I go back to the man living in the artist-designed public urinal; that he occupied a structure specifically designed not to accommodate the needs of the homeless can be viewed as an act of resistance. The same for Hammons’s performance and the men in Brixton who refuse to pay to perform an essential bodily function. When people are denied their most basic needs – housing, toilets, clean water – public art might become a site to express collective anger. Until there is complete system change and everyone can live in dignity, as Hammons said, keep the rage going.

Henry Broome is a writer and critic based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 477: June 2024.