Feature

Out of Actions

Robert Ayers looks back at three decades of Performance Art

The enormous, wide-ranging and really rather wonderful exhibition, ‘Out of Actions’, has been a long time coming, but perhaps that is understandable. Performance Art and its makers do not offer the most obvious opportunities for museum curators, and even an exhibition that ostensibly takes as its material the static traces that three decades of Performance Art have left behind must somehow include an easily comprehended account of the performances themselves. So perhaps this was an exhibition that was waiting for the technology that would allow it to happen. In ‘Out of Actions’ that technology has been used most impressively: every few yards as you make your way through the galleries you come across a video viewing station that allows you, with a simple sweep of a barcode reader, to make your choice from up to ten bits of film and video documentation. There are 92 pieces of footage in all and, although many of them are familiar enough, others have been newly unearthed by the show’s curators – and here they all are, in colour and with sound if they have it, dragging 20 and 30 year-old pieces of performance into immediate contact with one another, and with a new audience.

To be frank, this can be unsettling and confusing. The recently renamed Geffen Contemporary is what used to be called the Temporary Contemporary – a vast and rough-edged factory space in downtown Los Angeles into which the smooth white surfaces of a contemporary art museum have been dropped whole. The gallery walls do not come anywhere near to reaching the crumbling industrial roof yards above them, and if this offers a pertinent enough reminder of the irony of trying to corral this work into a museum at all – it was often made by artists who were consciously trying to escape the clutches of the gallery system – it also means that ‘Out of Actions’ is one of the noisiest, distraction-rich exhibitions that it has ever been my pleasure to experience.

Improbable and anarchic connections are struck up all over the place – hearing Gilbert & George warbling Underneath the Arches in the background as I examined Hermann Nitsch’s gore-spattered trophies has probably changed for ever, and for the better, my feelings about his Viennese Aktionen – but of course this is entirely in keeping with the spirit of much of this work. Indeed, Paul Schimmel and his curating team are to be congratulated on the extent to which they have been able to keep this spirit alive, for it is at the root of the show’s real success.

You might wonder about some of the emphases, raise an eyebrow at some of the juxtapositions, scratch your head at some of the omissions – no Robert Whitman, no Roland Miller or Richard Layzell or Richard Long, no Duchamp, for goodness sake – but in the end there is more than enough to satisfy those of us who have been sustained by (or contributed to) the remarkable history of Performance Art over the years.

Imagine it, here are many of the key works of an art-making ethos that has, despite being in constant danger of slipping off the edge of art history, established many of the assumptions about artistic practice across a far broader range of activity than Performance Art itself, or even the much looser category of Live Art that we have invented for ourselves in Britain. Among these are: the rejection of existing structures and of the necessity for intermediaries; a willingness to take one’s art to a public rather than assuming that the reverse will happen; the posing of the question ‘who is this art for?’; the presumption not only of the propriety of political content in one’s work but of direct political action in its mechanisms as well; an emphasis on process rather than product; the willingness to collaborate or to be one’s own administrative support; and having the courage to make direct physical contact with the people for whom the art is intended – all of these things are part of Performance Art’s noble legacy and it is moving to see the inventors of much of contemporary art’s ethical base honoured in this show.

‘Out of Actions’ includes Allan Kaprow and Tadeusz Kantor, Joseph Beuys and Chris Burden, Bruce McLean and David Medalla, Bruce Nauman and Paul Neagu, Vito Acconci and Laurie Anderson. There are the 16 Oldenburg ‘Store’ sculptures from the MOCA permanent collection and Ben Vautier’s reconstructed Gallery One shop window. There are Nam June Paik pianos and Rauschenberg’s Automobile Tire Print and – the beginnings of proper recognition at last – Carolee Schneemann’s Eye Body/Four Fur Cutting Boards Installation. There is more than enough Milan Knizák and Paul McCarthy.

But it is a measure of this show’s success that it overcomes its own exhaustiveness. It is not just all-encompassing, it manages as well to communicate the very different meanings and moods of the work that it includes. In the same room, you find the single photograph (of one of the ‘Suspensions’, predictably) that represents Stelarc; the table of whips and pills and knives and flowers and fluids and, most infamously, the revolver and bullet from Marina Abramovic’s Rhythm 0, and the series of projected slides of the audience using those objects upon her that is its documentation, and – completely new to me at any rate – the small framed black and white photograph entitled Tehching Hsieh Punching the Time CLock on the Hour that is the poignant record of the year(!) that the artist spent in ac age, dutifully clocking-in every hour.

There are problems that attach themselves to this exhibition, of course. Alongside the sculptures and the paintings and the costumes, it raises scraps of paper and fragments of shattered glass and snapshots and notebooks to the status of religious relics when many of them were made or just tossed aside by artists claiming that theirs was an entirely iconoclastic enterprise. Was it really though? So many of these photographs show audiences full of photographers and filmmakers, so many of these actions and gestures were carefully staged with a newspaper reporter at hand, so many of the drawings and newspaper clippings and items of stained clothing have been faithfully hoarded by the artists over the decades. Ultimately, it seems to me that much of this stuff was made with at least one eye focused on posterity and even when it wasn’t, the problems that are raised are the same ones attached to the presentation of any works in a museum context.

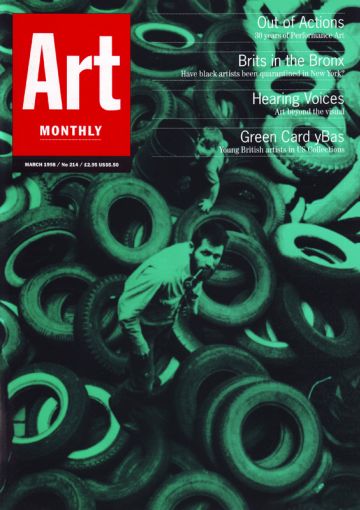

The more troubling issue for me is around the things that are not genuine relics at all: the recreated relics, if you like. Yoko Ono’s Painting to Hammer a Nail was originally made in 1961 but that wasn’t the one that I hammered my nail into last week (thus alarming a security guard, who asked in horror, ‘Excuse me, sir. Are you the artist?’ before I pointed out the instructions on the label); Kaprow’s Yard (originally the back garden of the Martha Jackson Gallery filled with old tyres and odd shapes wrapped in tarpaulins in 1961) is lovingly reproduced here in its own wire-link fence enclosure in front of the museum; and Raphael Montanez Ortiz’ Piano Destruction Concert is represented in the catalogue by a photograph that was taken in 1966, but imitated in the exhibition itself as a demolished piano which I stood and watched him destroy on the afternoon before the show opened.

As one might expect of a major exhibition of this sort, it is accompanied by a breeze block of a catalogue that offers any number of scholarly interpretations. Similarly, an opening-out of many of the issues that it raises is offered in the Reading Room that sits alongside the exhibition itself. But, if I need to register a serious doubt about the curatorial stance of ‘Out of Actions’, then it is to do with how it presents the sources of Performance Art and, on the other hand, its legacy. So far as sources are concerned, the exhibition relies upon the assertions that Kaprow came up with 30 years ago and gives Jackson Pollock the status of the font from which all things flow. Although he is portrayed (quite correctly) as having contemporaries in Europe and Japan who were dripping and splashing and scrawling with paint while other people watched them, and although his Number One is viewed at the beginning of the exhibition through the torn paper screen that is Saburo Murakami’s Entrance, his is the only moving figure that is seen outside of one of the viewing stations. Hans Namuth’s black and white footage of Pollock at work is presented on a video loop that plays on a large-scale screen set into one of the gallery walls. This affords it a very special status. By contrast, John Cage is underemphasised and the particularly European sources of his and other work are, notwithstanding the inclusion of Yves Klein and Piero Manzoni, rather too subtly hinted at or – more often – simply omitted.

If what comes before the chronological chunk that the curators of ‘Out of Actions’ have chosen for their specialisation is imperfectly dealt with, then there are questions as well about what comes after it, and why they chose to chop things off at 1979 anyway. It encourages the view (that I wanted to think was utterly discredited nowadays) that Performance Art was an art historical phenomenon tied to a particular period. It wasn’t. Generation after generation of young Performance artists, blessed with a ready ability to irritate and surprise and delight, are the living, walking proof of this although curiously enough I didn’t really get much sense of their presence in Los Angeles.

Still, this is hardly the fault of the creators of ‘Out of Actions’ and, whatever interpretative disputes I would want to raise with them, I would want to applaud at the same time the lucidity of their intentions in conceiving this show, and the tenacity that they have brought to bear on assembling it. These things will never be brought together again; I would recommend that you try to see them while you can.

‘Out of Actions: Between Performance and The Object, 1949-1979’ was at the Museum of Contempo-rary Art, Los Angeles to May 10 1998 then toured to MAC, Vienna June 17 to September 6; MACBA, Barcelona October 15 to January 6, MoCA, Tokyo Spring 1999.

Robert Ayers is a Performance Artist who is Artistic Director and Professor of the Contemporary Arts at the Nottingham Trent University.

First published in Art Monthly 214: March 1998.