Review

Open City Documentary Festival 2023: The Art of Non-Fiction

Alex Fletcher reports on the contested role of subjectivity in recent documentary filmmaking

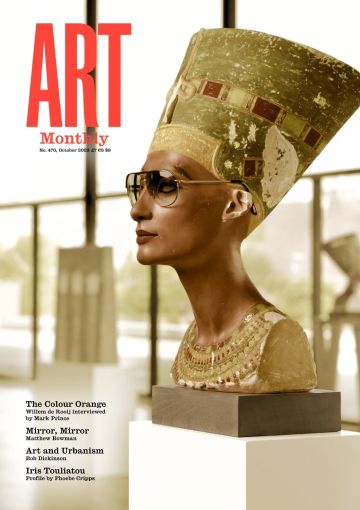

Riar Rizaldi, Monisme, 2023

Occupying various art and cinema venues across London, Open City Documentary Festival returned this year for its 13th edition with an ambitious and wide-ranging programme of screenings, events, talks, workshops and exhibitions. Spanning the domains of visual anthropology, experimental film and artists’ moving image, the festival celebrates the diversity and vibrancy of documentary as an expanded field of moving image practice, bringing together historical and contemporary works from around the globe that typically challenge the idea of what a documentary is and can be.

The so-called ‘documentary turn’ in contemporary art and the emergence of new digital technologies has in recent years created a fertile field of aesthetic and technological possibilities for the development of the documentary form. These possibilities were especially manifest in the two ‘In Focus’ sections of the festival, which focused on moving-image works by contemporary artists Mary Helena Clark and Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, as well as in the ‘Expanded Realities’ exhibition, which featured interactive and immersive films and video games employing CGI and VR technology. Breaking with conventional modes of documentary realism, these works variously employed the mediums of film, video and digital animation to probe the multiple and mutable realities of our world in often formally reflexive and imaginative ways. Yet whether such practices – which tended to place little or no importance on the referential dimension of images, oral testimony or other archival materials – should be conceived as working within or as extensions of the documentary tradition was not always convincing.

Documentary is an inherently slippery category which tends to elude definition. It is, perhaps, best defined as a mode of representation that foregrounds the indexical or evidential aspect of written documents or audio-visual records. It does not, however, mean the simple absence of fiction, as the related category ‘nonfiction’ suggests. For, as many point out, the transformation of documents into a documentary necessarily entails some degree of narrative construction or interpretative framing. This vexed relationship between indexical records and their artistic and discursive shaping is at the core of documentary as a critical method and practice, which, as Gilberto Perez argues, must continuously negotiate ‘that uncertain frontier where documentary and fiction meet’.

This frontier was more productively engaged elsewhere in the festival in a series of events and films dealing with the entangled geographies of colonial history. Exemplary here were the two latest iterations of Annabelle Aventurin and Léa Morin’s project Non Aligned Archives, in which the two archivists endeavour to reassemble and restore the fragmentary remnants of unfinished or lost works made by marginalised or forgotten African diasporic filmmakers. In the meticulously researched lecture performance And Everyday Exile, Morin pieced together various letters, photographs and films related to the Moroccan filmmaker Karim Idriss in an attempt to conjure an untraceable film he made in 1970. Akin to Saidiya Hartman’s method of ‘critical fabulation’, Morin marshalled these documents to tell a moving story about Idriss’s life in exile in Poland and France, as well as to illuminate the silences and halted dreams to which his scattered archive gives testimony.

The method of critical fabulation was also compellingly employed in two archival essay films by Sanaz Sohrabi and Miranda Pennell, which, in different ways, adopted essayistic and speculative narrative strategies to interrogate Britain’s colonial past. In Scenes of Extraction, 2023, Sohrabi reworks photographs and films culled from the British Petroleum archive, using collage and CGI maps to excavate the history of British oil operations in Iran during the early 20th century, as well as the implication of the camera in these extractive processes. In Trouble, 2023, Pennell investigates RAF survey photographs of Egypt and Iraq taken in 1928, carefully scrutinising how these images attempt to capture and control the region they depict. In both works, Sohrabi and Pennell notably turn to the language of spectres and the supernatural as a way to invoke the shadowy and ghostly presences concealed within these archival images, as well as to intimate the eerie ways in which past colonial injustices continue to haunt our contemporary world.

Haunting, as Avery Gordon contends, is a constituent phenomenon of modern social life, in that it registers the way in which ‘a repressed or unresolved social violence’ makes itself felt or known in the present. Such spectral and untimely presences, as Gordon underscores, trouble conventional ‘distinctions between what is (socially) real and what is fictional’, evading the grasp of positivist representational practices like the traditional documentary. In Riar Rizaldi’s Monisme, 2023, and Bo Wang’s An Asian Ghost Story, 2023, the two filmmakers respectively turn to the hybrid form of docufiction as a means to reckon with the ghostly and liminal realities generated by colonial-capitalist globalisation. In the former, Rizaldi interweaves documentary interviews with fictional episodes to create a multi-dimensional study of the scientific, mining and indigenous communities that live and work around Mount Merapi in Indonesia. In the latter, Wang combines archival and staged elements to explore the rise of Hong Kong during the Cold War to become the largest international exporter of human hair. For both filmmakers, the spectral emerges as an apt methodology for exploring realms of experience and truth that typically escape the reified binaries that define modern systems of thought, such as fact/fiction, science/myth and west/east.

In Miko Revereza’s Nowhere Near, 2023, the theme of haunting is approached through a distinctly autobiographical lens. Part diary, part essay and part detective story, the film documents the American-Filipino filmmaker’s investigation into the reasons behind his family’s status as undocumented immigrants living in Los Angeles. In inquiring into his family’s history, Revereza is gradually confronted with the transformative recognition that his personal identity is intimately imbricated with larger geopolitical forces that reverberate across generations and national borders: from the post-9/11 US immigration policy that derailed his parent’s visa claim to the Spanish and US occupations of the Philippines. As with the other standout works featured at the festival, the film’s interrogation of the uncertain frontier between documentary and fiction serves to affectively draw us in to reflecting on those dense sites where social reality and the spectres of history meet.

Alex Fletcher is a writer and lecturer based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 470: October 2023.