Feature

On Criticism

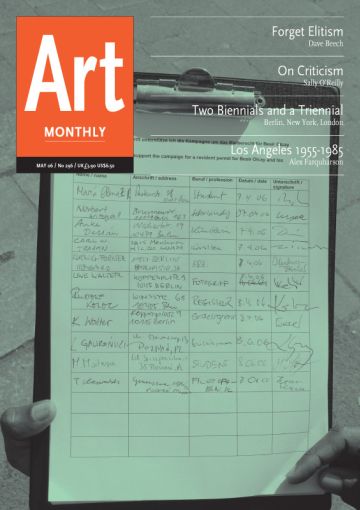

A matter of opinion or what? Sally O'Reilly provides some statistics

Graph of article data

One of the deepest insults most frequently levelled at art critics is that their writing is ‘merely descriptive’. This generally implies that the writer either lacks critical insight or is toeing the line, perhaps through cowardice or maybe because they are in the pay of the gallery. Historically, the criteria of art criticism have varied between contexts, from academia to journalism, but usually both artist and writer emerge relatively unscathed, with kamikaze attacks left largely to colourful columnists or infamous curmudgeons. Alternative nurturing functions of art writing might favour the artwork – affirming an artist’s practice or resuscitating neglected genres or the historically repressed – or assume the more neutral role of interlocutor between artwork and viewer. These functions of writing all require different emphases on inert description, thematic interpretation and qualitative judgement, but there remains no consensus on current requirements in the national art press.

The necessity for judgemental criticism is difficult to quantify, as the traditional relationships between artists, institutions, critics and collectors have shuffled confusingly in recent decades. The curator, for example, has overtaken much of the critic’s role in deciding who, to put it crudely, is in and out of the institutional stable. And throughout the pages of Art Monthly, writers’ bylines indicate how polymathic contributors are: we are also artists, curators, lecturers, art historians, theorists and editors. And there are many other distinctions that can be drawn between individuals: those that work from a preformed ideology and those that react reflexively to each exhibition, sometimes contradicting previous positions – in other words there are, as James Elkins has noted, writers with ‘stands’ and those with ‘stances’. Then there is the writing that manifests a belief in the continuity of art history and criticism, and that which reflects a pluralistic take on cultural production. Writers also possess and pursue varying levels of knowledge of and reverence for art history, critical theory and the history of art criticism itself. In short, the nature of criticism is as divergent as flora and fauna, or as chaotic as a field of weeds.

To return to the issue of the adjective ‘descriptive’ being used as an insult when applied to criticism: the Columbia University National Arts Journalism Program conducted a survey of the top 230 art critics in US national daily and weekly titles in 2002, which found that the least popular function of art writing was that of judgement, while the most popular was simply description. This might be explained in a number of ways. It might be down to the control of the art market over the entire field of practice, producing an atmosphere of caution, or even the extraneousness of the critic. Or, a finer point, as Benjamin Buchloch described it in a round table discussion subtitled ‘The Present Conditions of Art Criticism’, published in October, Spring 2002: ‘The judgement of the critic is voided by the curator’s organizational access to the apparatus of the culture industry (eg, the international biennials and group shows) or by the collector’s immediate access to the object in the market or at auction.’ Another reason might be a writer’s self-perception as provider of information, shuttling experience from artwork to reader through an impassive mode of writing devoid of qualitative judgement. Art writing as a historical primary source takes responsibility for art history on the hoof, but it seems improbable that an involved individual could provide a record to be interpreted or contextualised according to external frameworks, while remaining neutral itself. In What Happened to Art Criticism?, 2002, Elkins outlines many additional shades of explanation for descriptive writing: for instance, the proliferation of styles since Pop have made rigid judgement inappropriate; Hal Foster’s insistence, iterated in the October round table discussion, that his generation worked ‘against this identification with judgement’ as a reaction against Clement Greenberg; or the recent centring of methodology, process and subject matter and the subsequent marginalisation of value.

This variegated account of the description epidemic is emblematic of the fractured understanding of what a critic is. Most writers in the review section of this magazine will have been trained in some other discipline; many are autodidacts and have hermeneutically developed habits and proclivities, which slop between writers and publications. We are all writing in response to one another, yet we are unused to criticism of our criticism, or even admitting that there are typologies or tendencies. For instance, regular readers might well recognise the oppositional adjectives chestnut – ‘the painting is at once alluring and repulsive’ – or the inevitable downwards slope of tone towards the end of a review, levelling out at a conclusive horizon in the final sentence.

This feature came out of a conversation about the ease of writing a negative review, compared to a positive one, and the rumination that this might lie in the English language: a preferable or wider vocabulary for the damning over the laudatory, perhaps. After scrutinising the review section of this issue prior to publication, however, I noticed that, in fact, it is sometimes rather difficult to discern if a review is positive or negative. It seems that the dialogical context of Art Monthly – in which justification is required for claim and counterclaim – muffles declarative language. In place of the straightforward use of superlatives or even adjectives, it seems that writers favour the marquetry of metaphors and similes to convey an image and an exposition of that image all at once. Often a text is so infused with metaphorical linguistic expressions that it is difficult to separate the literal from the figurative. Metaphor is descriptive writing off-road, invoking a tangible phenomenon to discuss something more abstract, and many writers employ it at the crucial moment – often in or near the final sentence. Like looking at the eclipse in a bucket of water, the critical event is to be looked at askance.

So, a scale might be drawn, with mimetic description at one end and the opinionated rant at the other. While one sample of writing would follow the form of an artwork, the other draws the artwork towards it, effectively sieving it through its own mesh. What is surprising, however, is the scarcity of either extreme. Without wanting to sound defensive – and I agree that there are many, many problems with art criticism at the moment – it does not hold true that we are, in the majority, merely descriptive. Perhaps the accusation should be redrafted to take into account our metaphorical constructions that engulf artworks and sweep them away on hyperbolic waves of our own conjuring.

NOTES ON THE STATISTICS

The key denotes four operative modes of a sentence or subclause: DESCRIPTIVE (Desc), CONTEXTUALISING (Cont), INTERPRETATIVE (Int) and AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL/OPINION (Opin/Auto).

By descriptive, I mean passages that convey what an artwork looks like, how it is arranged or some other factual aspect of the exhibition. Any description that also involves an exegesis of the artwork – an evaluation of how it is perceived, an exploration of its themes, the consequences of its effects, and so on – has been included in the interpretative category.

Contextualising is defined here as any discussion of art history, critical theory, politics and so on that, although not intrinsic to the artwork or exhibition, adds to an understanding of it. This also includes discussion of previous work by the same artist, which is infrequent, as the show under review is generally prioritised.

The conflation of opinion and autobiography is necessary so that, in many cases, either modes of writing would register at all. It is interesting that the unsubstantiated pronouncement of greatness or otherwise is as rare as the self-indulgent. The only time anyone comes close to this is JJ Charlesworth’s ‘brilliant’, which he attaches to the comedian Simon Munnery, and has nothing whatsoever to do with the exhibition under discussion. The belletrist autobiographical style seems to be out of vogue too (for a discussion on this see Alex Coles, ‘The Bathroom Critic’, in AM263.)

There are instances when the above classifications were ambiguous. For instance, Alex Farquharson’s interpretation of the work in ‘Los Angeles 1955-1985’ could very well be considered art historical contextualisation – a distinction that also blurs when artworks are steeped in art historical references. Statistics are notoriously subjective and here some categorisations may well be disputable.

The figures below the X-axis are the description coefficients of each writer. This value is arrived at by dividing the word count of purely descriptive passages by the overall word count and is expressed in the graph in percentage form by the black bars.

Sally O’Reilly is a writer and critic and co-editor of Implicasphere.

First published in Art Monthly 296: May 2006.