Feature

Not in Our Name

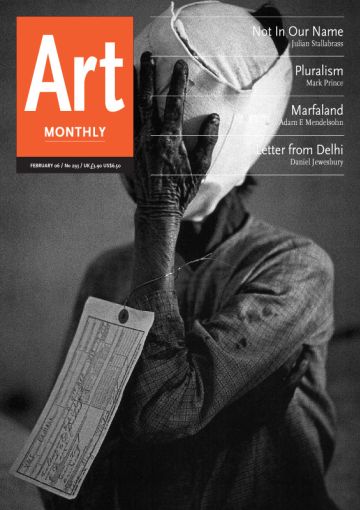

Julian Stallabrass looks at Iraq through the lens of Vietnam

The images are still in many people?s heads a generation after they were made: Malcolm Browne?s photograph of the priest Quang Duc?s self-immolation by fire; Eddie Adams? photograph of the summary execution of a guerrilla suspect by Saigon?s chief of police; Ron Haeberle?s terrible pictures of the dead and the soon-to-be-slaughtered in My Lai; many images by Larry Burrows, Philip Jones Griffiths, Don McCullin and Tim Page. In the late 60s and early 70s, photographic images of the Vietnam War played an important part in shifting opinion against the conflict, in the US and elsewhere. The unprecedented phenomenon of a people not merely protesting against the actions of their own troops but willing the enemy to victory became commonplace, if never internalised by the nation in which they were born. Yet how are such images remembered, and what does their remembrance mean in the present?

In much art writing, a reflex Freudianism governs what passes for the analysis of memory. It is ignorant of or wishes away the thorough theoretical and scientific discrediting of psychoanalysis, and the 20 years or so of extraordinary research on the brain that has not merely proven its faults but has offered a complex, unexpected and fertile alternative. Some of the fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis, notably repression, which have become so worn with use that they are now taken as commonsense, have remarkably little relation to what is known about how minds work. The art world?s model of the mind remains stuck in the past, as does the aspect of its radicalism that has such faith in the power of culture, that it is happy to fix the superstructure and let the base look after itself.

One finding of modern research into memory is that individuals are more likely to remember events in the state that the memories were originally laid down; to remember something that happened when you were drunk or stoned, you should get drunk or stoned; you are more likely to remember happy memories while happy, sad ones while melancholy, and so on. A similar process appears to affect the social memory for events: in eras of political radicalism, activists look to their predecessors for ideas and images. So 60s leftists looked to the 30s, reviving interest, for example, in the forgotten Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs of the Depression era. We do not have to search far for the reason behind the revival of interest in the films, photographs and literature of the Vietnam War today, or the resurrection of the ideological divide across which that material is seen: was the war an honourable venture turned bad, or an imperial lesson taught the world through the attempted genocide of a peasant people and the ecological destruction of their land?

Painful though they are, the revival of these memories, despite and/or because they make the present more unbearable, has a definite use. Through striking similarities and differences, Vietnam can serve as a point of reference against the war in Iraq. Among the similarities, the murderous behaviour of US forces stands out. As in Vietnam, it is fuelled by racism. The use of artillery and bombing against civilians, snipers murdering children, shooting at ambulances, the spectrum of violence from the most impersonal (carpet bombing) to the most intimate (torture) have barely changed. What was famously said of Ben Tre (?it became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it?) could also be said of the city of Fallujah. Websites allied to the insurgency, or simply opposing the occupation, are heavily reliant on documentary images of the results, from the thousands of pictures of civilians killed or injured by US troops to the panorama of petty humiliations endured by Iraqis, detained, kneeling, bound, faces pushed into the dust by soldiers? boots. Another salient similarity is the utter corruption of the administration installed and supported by the imperial forces. In South Vietnam the government was famously venal, and its larcenous tendencies extended from its pinnacles to its lowest soldiers, who eked out their inadequate wages with bribery and theft. In Iraq, billions of dollars of reconstruction and security money have vanished into the US-Iraqi kleptocracy.

Yet the contrasts are equally great. When the US began to intervene in Vietnam to prevent the election of a popular nationalist government, it propped up the old colonial Catholic regime that had been set in place by the French. This was to follow the familiar pattern of imperialist intervention. By contrast, in Iraq it deposed its own former client, and in doing so began to hand power to the majority underdogs, the Shia. The dispute between the Sunni, the Shia and the Kurds, based on ethnic and religious differences and the struggle over oil riches, is hardly one that most people in the West can identify with, as many could with the popular and principled communism of the National Liberation Front (NLF, often known in the West as the Vietcong) and North Vietnam.

The response of the US military to its defeat in Vietnam was to remake its strategy in the negative image of that war, and much of that strategy was about image management. Journalists and photographers, dependent in many ways on the military in Vietnam but free of formal censorship by the armed forces, have been formally embedded with the troops in Iraq, and their output is thus controlled. While enemy bodies (very often non-combatants) in Vietnam were obsessively counted as a way to register progress in the war, in both wars against Iraq no count has been made, and every effort has been taken to keep bodies out of sight. In violation of the Geneva Convention, the bodies of enemy soldiers were bulldozed into the sand, uncounted and unidentified, and the US refused to identify the burial sites; relatives of many Iraqi soldiers from the first war still have no certain knowledge of the fate of their loved ones. The Empire, then, can and must produce corpses but should as far as possible avoid the production of their images.

The contrast, though, goes beyond the attitude of the imperial administration. The insurgency feeds off Islamic fundamentalism, and has been ruthless in its prosecution. The NLF relied on the goodwill of the people who protected them; they deposed landlords set in place by the Catholic regime, and rarely stole goods or harmed the peasantry. The insurgency, in contrast, not only targets the servants of the imperial regime but slaughters Shia people without discrimination. Their attitudes to western journalism could not be more different from those who opposed the US in Vietnam. The NLF used their spies to gather information about the movement of journalists and photographers to try to protect them from harm. They were well aware of how their stories and images helped change public opinion in the West. The insurgency takes journalists hostage and has killed many of them. As Patrick Cockburn points out in an interview recently published in New Left Review, the situation has become so dangerous that some of the insurgency?s greatest triumphs go unreported in the West.

The result, particularly in the US, is that the mainstream news media are gagged by both sides; by the insurgents and fundamentalists who expect nothing of them; and by the power of conservative proprietors and advertisers, who have ensured a more smoothly controlled and homogeneous media universe than previously obtained. If radical political comment has migrated to theatre, comedy and the internet, it is because it has been driven out of mainstream media discourse.

Modern memory research offers disturbing findings about the functioning of the mind in these conditions. The components of memory are modular and can be separated into different types; among the many discriminations, source memory, the memory about how and when we came to learn something, can often become detached from what has been learned. People have difficulty unlearning new information which is subsequently found to be false. The lavishly funded propaganda machines of the CIA, not to mention the cabals of the Bush administration, find willing allies in the giant media corporations, and aside from outright lies, their ideological assumptions are built deep into the very language and presentation of television and newspaper reporting. In such a media-saturated environment, many still hold discredited lies to be true (that Iraq was implicated in 9-11, for instance), and who of us can honestly claim to have much hold on the source memories that underpin our political beliefs?

Sources for media outside the mainstream have of course grown precipitately since the founding of the web. The full spectrum of opinion over Iraq from leftist to fundamentalist and imperialist is immediately available online in a way that the samizdat publications of the anti- Vietnam War movement never were. Image-making technology is cheaper and more accessible, and is easily linked to digital distribution. So, if you want, you can see the perpetrators? own videos of car bombings and beheadings. It is one of the great contrasts between Iraq and Vietnam, at least so far, that the images that stand out in the memory of the Vietnam War were taken by western professionals, and came to be read in the light of the opposition to it; perhaps because of the energetic attempts to massage the media image of the war with staged events, such as Bush?s victory landing and the toppling of Saddam Hussein?s statue, as well as the hostility of the insurgency to journalists, the most striking images that have come out of Iraq were taken on cellphones by torturers.

While celebrated images of the war in Vietnam took a hold over many minds, there were two missing image ?archives? of the war, one seen in the West only a generation after the end of the war, the other still hidden. The first was the extraordinary photographs taken by the NLF and the North Vietnamese army themselves, by Minh Truong, Doan Cong Tinh and many others, with extraordinary ingenuity and in conditions of unimaginable hardship. Through the efforts of Tim Page and others, these have finally come to light in exhibitions and publications in the US, and they are a revelation of the other side whose faces, motives and tactics remained invisible in the mainstream western media. The second is the amateur productions of the US forces themselves, many of whom carried cameras, and many of whom photographed the atrocities that they committed (just as they do today). Another gruesome image archive of that war, that tells its own truth, exists, hidden in the attics and crannies of thousands of US homes. Perhaps the new technology will mean that this time such images are harder to secrete from the public eye.

Radical photographs of the Vietnam War came to be consistently published in the mainstream press because of a split in the US elite, a substantial section of which thought that the war had become so divisive and above all expensive that it threatened the nation?s global dominance. These images came to take on great power as indications of far more than they could actually show, as registers of the torture and genocide of a people who had the temerity to resist imperial dictates. The anti-war movement failed in its immediate aims but the split in the elite and the shift in public opinion drove Nixon to pursue a programme in which the Vietnamese would take over the prosecution of the war as US troops were slowly withdrawn. Given that the client regime was fantastically corrupt, incompetent and unpopular, this programme led to communist victory.

In many circles, the images of the war in Iraq have yet to have the effect of gathering about themselves the wider meaning of terror perpetrated by the West, of the arbitrary exercise of violent power. Mainstream opposition leaders in the US (and even the UK) have not declared themselves to be anti-war, or even unequivocally anti-torture. The insurgency is nearly as unsavoury as what it opposes. Yet the war, and the revivification of memories of older imperial adventures and the resistance to them, presents an opportunity to assemble the elements of a counter-hegemonic movement in which images must necessarily play a large part. In this new environment, it is evident that the injustices and atrocities committed in our name must be focused on. We should make, search for, circulate and reactivate images (as many artists did in opposition to Vietnam), producing a counter-memory and counter-currency of images to the salving novelties of the BBC, Sky and Fox News. We must aid source memory by insisting on the contextualisation of images, and on the building of those images into consistent, oppositional world-views, as Philip Jones Griffiths did in his model book, Vietnam Inc. The prima- cy of the image in the mass media gives artists leverage, and the web gives them the means, to have an influence on the political world. It is time to exercise it.

Philip Jones Griffiths with an introduction by Noam Chomsky, Vietnam Inc., Phaidon Press, London, 1971, 978 0 7148415 2 6.

Julian Stallabrass is senior lecturer at the Courtauld Institute, London.

First published in Art Monthly 293: February 2006.