Feature

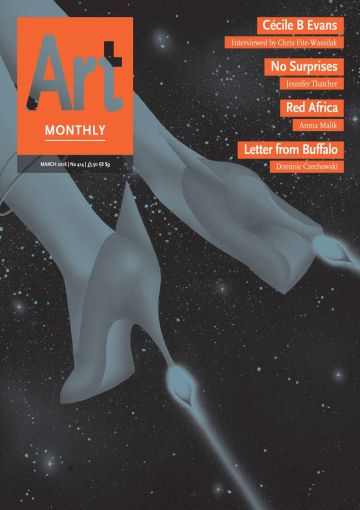

No Surprises

It is time that the art world put its own house in order, argues Jennifer Thatcher

For too long galleries – both private and public – museums, universities and other cultural organisations in the UK have ignored the true scale of sexual and other abuses in the arts.

On 30 October 2017, the Guardian published an open letter written by 150 ‘workers of the art world’, in the wake of sexual allegations against Artforum co-publisher Knight Landesman (Artnotes AM412). By this point, the letter had already been circulated via social media and attracted over 2,000 signatories, including many high-profile names. The number rose dramatically over the next few hours, as the letter continued to be published across international news outlets, to over 9,500 before the list of signatories was closed at 12.00am PST on 30 October 2017, the response having overwhelmed the ‘exclusively volunteer-driven undertaking’. The letter began with the arresting statement: ‘We are not surprised.’ It continued: ‘We are artists, arts administrators, assistants, curators, directors, editors, educators, gallerists, interns, scholars, students, writers, and more – workers of the art world – and we have been groped, undermined, harassed, infantilised, scorned, threatened, and intimidated by those in positions of power who control access to resources and opportunities. We have held our tongues, threatened by power wielded over us and promises of institutional access and career advancement.’

The letter had begun, gallerist Emma Astner tells me, as a discussion between eight Instagram members before it was moved to the more secure WhatsApp and the team communication app Slack. The group, 150-strong within a day, began to organise two-hour rota slots to cope with emails. Since the first Harvey Weinstein allegations were printed in the New York Times on 5 October 2017, it had seemed only a matter of time before similar allegations were made in the art world. As Astner attests, ‘it was obvious that it was an urgent issue’, and people were ready; busy people cleared their diaries, placed trust in strangers and wrote the letter together. Incredibly, only one person dropped out at this stage. Everyone else agreed to write in a unified voice that included women, transgender, non-binary and gender nonconforming people living in all time zones, and working in all areas of the art world.

The letter explicitly critiqued the quick-fix solution of Landesman’s resignation as Artforum co-publisher, demanding serious analysis of the ‘more insidious problem: an art world that upholds inherited power structures at the cost of ethical behaviour’, adding that this case was hardly a one-off: ‘Similar abuses occur frequently and on a large scale within this industry.’ The number of recently publicised cases in the US – implicating amongst others publishers, curators, collectors, artists and professors – explains why the American section of We Are Not Surprised (WANS) is particularly large.

The problem that WANS organisers faced was how to avoid falling into a similar trap of a sensationalist, quick-fix solution. A letter was not going to be enough. To this end, a website (www.not-surprised.org) and various social-media handles have been set up, the former including a definition of the term ‘sexual harassment’ that seeks to set it in the context of the wider abuse of power rather than as an isolated, sexually motivated act: ‘Sexual harassment is rarely purely related to sexual desire. It is often a misuse and abuse of power and position, whose perpetrators use sexual behaviour as a tool or weapon. It is predatory and manipulative, often used to assert the superiority or dominance of one person over another person.’ In February 2018, the homepage of the WANS website was updated with a new statement, calling on supporters to boycott Artforum, in the light of the fact that Landesman remains co-owner, and that ‘Artforum’s publishers and lawyers filed a motion to dismiss [former employee] Amanda Schmitt’s lawsuit’. On 9 February, Artforum released a statement confirming that while Landesman does still retain shares in the company, he has been removed from the board of directors and retains no voting rights. Artforum also claimed that their ‘attorney is submitting arguments to dismiss the case against the magazine, and not the case against Mr Landesman’ – a point which Schmitt’s legal team claim is untrue, according to a statement published in ARTnews.

There is no doubt that social media greatly facilitated the speed and scale of the response by WANS, and it is interesting to speculate whether instances of historical harassment might have been caught out (quicker or at all) if social media had been around. If social media encourages victims to share sensitive stories amongst a trusted circle of friends, the increasing prevalence of online trolling and recent phenomena such as revenge porn have made many nervous of information getting into the wrong hands or inciting a vicious backlash. An artist who broke a story about sexual abuse on Facebook in response to the #MeToo campaign, and who now wishes to remain anonymous, told me that she had since retreated from the social-media site, having been subsequently trolled: ‘It made me realise that any vulnerability you ever expose is likely to be used against you.’ The public nature of some social-media sites, like Facebook, mean that exposing an alleged harasser online can also leave one vulnerable to counter-claims of libel.

It was telling that the WANS letter was published in the UK by the Guardian, the most liberal of the former broadsheet newspapers and which regularly covers contemporary art. In doing so, it brought to attention the hypocrisy of the art world’s cherished liberalism – something that Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid had already started with her Negative Positives project (2007-), which invites spectators to consider the newspaper’s sustained racial prejudices. On 14 January 2018, the Guardian’s sister newspaper, the Observer, was the first to break the story of allegations against former London gallerist Anthony d’Offay (Artnotes AM413), in an article by in-house writer Ben Quinn and Art Newspaper editor-at-large Cristina Ruiz (the teaming up of the two publications arguably suggesting that the Art Newspaper perhaps feared facing any legal backlash alone). To the list of historical allegations (1997-2004) by three women, including public humiliation, unwanted sexual advances and professional punishment on refusal, it was noted that d’Offay was currently under police investigation for ‘an allegation of malicious communications’, although no further details were offered. The next day, the Guardian’s arts correspondent Mark Brown reported that Tate and National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) – to which d’Offay sold a large Artist Rooms collection in 2008 at the price he had originally paid – had suspended contact with him, pending the investigation. That same day, Javier Pes, writing for Artnet, pointed to the coincidence that d’Offay had already stepped down as ex-officio curator of the Artist Rooms collection on 19 December 2017, ‘one day before the police received the allegation’. Artnet quoted another former d’Offay employee as being ‘not surprised’ by the allegations. Clearly, Tate and NGS have been put in an incredibly uncomfortable and compromising position.

I worked at Anthony d’Offay Gallery during the period of time under investigation – a time when the gallery was at its largest (around 30 staff, of whom many were young women in their 20s). In my direct experience, bullying was explicitly acknowledged as part of the gallery culture. In my first week, I was asked by senior management whether I would be a ‘bully or a victim’; I replied, ‘neither, thanks’, to which the response was, ‘good luck, because that’s how it works here’. Another employee told me they remember similarly hearing from senior management that ‘bullying brings out the best’ in people. I recently spoke at length to eight former d’Offay employees from that period, all of whom used similar language to describe the unhealthy atmosphere of the gallery, which, as one employee expressed to me, was ‘run on fear and stress’. These employees also told me of having been regularly reduced to tears through exhaustion (‘you could never work hard enough’), being shouted at or humiliated in front of staff or clients, and their frustration at never seeming able to get things quite perfect enough. It seemed to me, through my experiences and from listening to my former colleagues, that there was a lack of normal boundaries between public and private spheres. Former staff recounted to me tales of being asked inappropriate questions about their personal lives, regularly being telephoned out of office hours – first thing in the morning or late at night when a particularly important client was in town – and being expected to go to d’Offay’s house on a Sunday (‘he was in his dressing gown’) or on bank holidays. Many employees recalled the constant fear of being fired. I personally witnessed one sales director who, wanting to avoid being fired for having sold the wrong work to collectors, asked the gallery artist to change the title of an artwork. The artist agreed. For my part, the solidarity of laughing in the pub with colleagues made work just about bearable. When the film The Devil Wears Prada came out in 2006, satirising the high-pressured, all-consuming world of a fashion magazine, former d’Offay staff said to me that they instantly recognised parallels with gallery life as we had experienced it.

The questions many of us in the art world have been asking ourselves since that time, and particularly in recent months, are: why do people stay in abusive or coercive situations? What makes employees vulnerable to emotional bullying and psychological manipulation? Why did no one speak out publicly until recently?

In the case of the Anthony d’Offay Gallery there were a number of factors. Friends outside the gallery, both at the time I was there and since, referred to d’Offay Gallery’s cult-like reputation. Indeed, former employees recalled being taken to visit d’Offay’s Hindu temple, or being invited to eat lunch cooked by his macrobiotic chef, or being referred to his private practitioner of alternative medicine. Many felt trapped emotionally by the gallery; there was a sense that you were lucky to work there. In my personal direct experience, there was no neutral person outside d’Offay’s inner circle with whom to discuss any grievances, and you therefore felt unprotected. The strong sense of hierarchy also kept people in their places. At the bottom of the rung, junior staff like me felt that they could not afford to leave without another job lined up; at the top, I would imagine that high salaries were difficult to give up. For many, as was my case, this was their first major art-world job, and we had no idea if all employers in the field were like this. Along with White Cube and Lisson, the gallery was one of the most well-known both in London and internationally. Gallery artists were world famous. Many private collectors were unbelievably rich and powerful, sometimes also celebrities in their own right, and renowned museum directors were always dropping in. That mythical combination of wealth and power could be very intimidating as well as exhilarating. In my first role as gallery receptionist, I would hear phrases that I had only heard in movies, like: ‘Don’t you know who I am?’ and ‘I am the biggest collector in’ – I forget which US state. Whatever their misgivings, several former colleagues mentioned to me their admiration for the efficiency and meticulousness with which the gallery was run – a standard reached by few other organisations – and I personally admired how much of the gallery’s time and attention was given over to relationships with artists, and how public collections were consistently prioritised over private collectors.

Although I did not experience sexual harassment at Anthony d’Offay Gallery, I was not surprised when I heard that others, whose opinions and word I respect, did. We all witnessed inappropriate behaviour that seemed designed to produce discomfort. When, during my time there, three young female colleagues left the gallery abruptly and without explanation, I remember fellow junior staff members, including myself, feeling nervous about what would happen next, but I guess that the busy life of the gallery meant that suspicions were brushed aside. The Observer article cited the existence of one non-disclosure agreement (NDA) signed as part of a legal settlement. This is key: NDAs play a significant role in why historical cases can take years to surface. My understanding is that in principle an employer would be within their legal rights to seek damages if an NDA were broken by an employee; although if the case were of significant public interest, and other people were prepared to speak out, that employer would be less likely to win in court. Still, it takes great courage to risk this.

One of the impetuses behind WANS, Emma Astner told me, was the fact that mainstream media are often only interested in black-and-white cases of harassment, where police or courts have been involved, rather than the grey area of unacceptable behaviour that so many of us in the art world have witnessed and experienced. Workplace harassment was legally defined in this country’s Equality Act of 2010. However, the recent case of the sexual harassment of hostesses at the Presidents Club exposed some of the possible loopholes in the law: agency workers of the event had to sign NDAs before they started their shifts. The government has now promised to look into the use of NDAs, particularly when used to silence workers involved in sexual harassment cases. The other major problem is that employment tribunals are only likely to consider cases if the worker makes the claim within three months of the alleged incident, effectively providing no legal framework for dealing with so-called historical allegations. Three months is far too tight a window, and it is pleasing that the Fawcett Society’s Sex Discrimination Law Review, published in January 2018, recommends an increase of that window to six months – if only in the case of pregnancy and maternity discrimination cases.

Furthermore, what is reported in the media is only the tip of the iceberg. Fear of expensive libel suits is an obvious deterrent, although the UK’s Defamation Act of 2013 offers publishers a defence if ‘the statement complained of was, or formed part of, a statement on a matter of public interest’. One must also be sensitive to the shame and psychological distress that surfaces when these cases, historical and current, are discussed publicly. Three former d’Offay employees did not want to talk to me in relation to this article; one explicitly because of the difficult emotions it brought up.

But what of commercial galleries today? The fact that many women are still expected to begin their careers as sales assistants or on reception desks – ‘candy up front’, as one gallerist apparently calls them – perpetuates the sexism and inequality in the commercial art world. One current gallery employee I spoke to admitted that in the three years they had worked there, front-desk staff had all been women, and only two interns had been male. Was it because a disproportionately high number of women had applied for these jobs? Or possibly because of the way the job adverts had been written? A quick search through current vacancies in the commercial sector is revealing: the lower strata jobs frequently make reference to appearance, usually before any interest or experience in art is mentioned. An ad for an ‘executive front desk associate’ for a New York gallery calls for a ‘polished appearance’ (as well as an MA). Another New York gallery specifies: ‘Qualified candidates should be highly personable, organised, motivated, and responsible, with a polished appearance and an interest in gaining experience in the daily operations of a contemporary art gallery.’ Within sales, the power relation continues to be structurally unbalanced by the fact that young female sales assistants often deal with older male clients. Pressure to seal a deal with the client – for the gallery’s sake or for the bonus attached – adds intensity to these meetings.

Nonetheless, as commercial galleries are becoming more corporate, they are themselves under pressure to safeguard their international reputations. On the very day the WANS letter was published, the gallery employee I spoke to was pleased to report that their gallery called an emergency staff meeting to discuss policy towards bullying and harassment. A code of conduct is currently being drafted. In the meantime, the employee also reported to me, a client who had behaved inappropriately to them was recently escorted out of the gallery. Robust in-house policy like this is crucial to protect employees from third-party harassment, such as from clients.

The public sector is hardly immune to sexual harassment. Through freedom of information laws, the Observer recently listed a handful of allegations reported in UK museums – at the Science Museum, National Gallery, Natural History Museum and Royal Museums Greenwich. Despite the low official numbers, Arts Council England has not been complacent. This autumn ACE circulated a memo to its National Portfolio Organisations reminding them of their ‘obligations under the terms and conditions of their grant to comply with any relevant laws or government requirements and comply with best practice in governance, reporting and operation’. Moreover: ‘These policies should be meaningful, and taken seriously by all staff and Board members.’ ACE is busy drawing up new terms and conditions for its organisations which should be available to view in March.

This reference to board members is significant. In recent years, boards have slowly become more diverse, and begun to include more artists and peers, but nepotism continues to cause problems. That is, when board members appear to be too close to the director of an organisation, then staff can feel that the board will be necessarily biased in the face of grievances and allegations against the director. One solution is to ensure that board members serve fixed terms, rather than stay on for long periods. ACE does not currently make any recommendations to this effect but it would make for good practice. The other major problem in public organisations – and indeed many commercial arts organisations – is that HR departments are rare, or if an HR officer exists, they may be carrying out other non-HR duties and thus there may be conflicts of interest. One public institution suggested offering staff a helpline to an external HR company. Unions also seem to be waking up to harassment issues. Sarah Ward, national secretary of media and entertainment union BECTU – newly merged with the larger Prospect union – wrote in a blog post on 2 November 2017 about workplace abuse of power, urging members to shout: ‘This is not OK, and you don’t have to put up with it.’ The recently founded Artists’ Union England offers its members free legal advice. Those without a union may find that other employment solicitors will offer 15 minutes’ free advice – important given that legal aid for civil (non-criminal) cases has been severely diminished following the introduction in 2012 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO). When I asked for a recommendation, ACE suggested contacting the free and independent Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS): www.acas.org.uk.

Of the 50 trusted friends and colleagues I contacted for this article in addition to my former d’Offay Gallery colleagues (via a group email to avoid singling people out), two came forward with details of bullying at separate public institutions. Neither of the two took legal action at the time; both regret not having done so. Neither institution had an HR department. The first person told me that they felt they were being pushed to resign, and that four colleagues endured similar treatment and also resigned. The second person, who was in a senior management position, told me that their line manager became increasingly controlling, not allowing them to do anything – not even leave their desk – on their own without explanation. Their colleagues had noticed the abusive behaviour and suggested rational tactics to deal with it, which failed. The employee was eventually sacked but felt unable to challenge the decision since a board member in whom they had confided said that the board would back the employer. In both cases, the victims are still distressed and furious, with fears for their future careers, particularly in a relatively close-knit world where rumours can do significant damage – as those who are now accused of harassment are finding.

For victims of harassment, the feeling of psychological failure can last years; that sense that one should have stood up to the bully, that one should not have been silenced. But the culture of silencing is very powerful and has deep roots. In her book Women & Power: A Manifesto (a transcript of two lectures at the London Review of Books), classicist Mary Beard traces the first recorded instance of a woman being publicly silenced to an episode at the start of Homer’s Odyssey ‘almost 3,000 years ago’. The point she makes throughout the lectures is that gendered assumptions about who has the right to authoritative public speech (Greek: muthos) have not been sufficiently challenged; that ‘we need to go back to some first principles about the nature of spoken authority, about what constitutes it, and how we have learned to hear authority where we do’. Rebecca Solnit’s recent book of essays The Mother of All Questions: Further Feminisms analyses the many reasons behind women’s silence. She notes a key change in Sigmund Freud’s attitude towards women as particularly damaging: that he stopped believing that his female patients had been sexually abused. She says: ‘If they were telling the truth, he would have to challenge the whole edifice of patriarchal authority to support them.’ Instead, he chose to believe that they were fantasising about these sexual encounters instead. Solnit reminds us that, in the US, it was not until the 1970s that a legislative framework and support network for dealing with sexual abuse, domestic violence, rape and incest, and abuse towards children was instituted. The term ‘sexual harassment’ only reached the mainstream in 1991 in the US, and soon after internationally, in the wake of the case of Anita Hill, whose boss – a Supreme Court nominee – had made her listen to him talk about pornography and his fantasies, and pressured her to date him.

Academia has been slow to respond to harassment, despite its widespread prevalence. Many art school staff prefer to see themselves as individual practitioners rather than managers who have responsibilities to the employees and students in their care. Art schools and departments should, many would argue, encourage freedom and experimentation without judgement; the intense relationships with supervisors and the lack of boundaries between work and play are an important part of the learning experience. Older British friends and colleagues recall that it was commonplace for tutors to sleep with students in the 1970s and 1980s. After all, everyone is an adult, and therefore acting of their own free will. In retrospect, however, the same friends acknowledged that ‘many of us believed a load of rubbish about ideas of sex and liberation’. Unfortunately, it is still not uncommon for people in a position of authority to punish those who refuse their advances, or when relationships go sour. This is particularly an issue if that person is your main supervisor or responsible for assessing your work.

While women now outnumber men at many art education institutions in the UK, men still hold a disproportionately high number of the senior roles: fewer than a quarter of all professors are women, nationally, according to professor Jane Powell (of Goldsmiths, University of London, which has a marginally better ratio of male to female professors). Once again there is a structural imbalance between a high volume of young or junior women in an environment presided over by older, senior men. The fast turnaround of students also provides an ever-fresh supply for serial predators to target. I have heard of one such predator who has been protected by his prestigious institution for 15 years, if not longer, despite direct complaints to other staff . Yet those I have approached about it will not divulge details since he is still in a position of power in a relatively small academic field. There should no longer be any tolerance for open secrets that allow people to continue operating with impunity.

The UK-based 1752 Group describes itself as ‘a research and lobby organisation that tackles staff-student sexual misconduct in higher education on a national level’. It is named after the £1,752 allocated to the first UK staff-to-student sexual harassment conference held at Goldsmiths in December 2015, from which the group developed. One of its priority strategies is to ‘instigate a national conversation on disciplinary procedures for staff members moving between institutions and data sharing across institutions’, claiming that: ‘At present staff members can opt to “leave” or “resign” during a disciplinary process, without any record of a formal complaint of sexual misconduct ... These individuals can then seek employment elsewhere.’ In the absence of widespread research carried out in UK universities since the 1990s, the 1752 Group and the National Union of Students have carried out a survey on the extent of staff sexual misconduct in higher education, results to be published this spring.

In the meantime, a Guardian survey last year concluded that 32% of universities had no student-staff policy. Many are seeking to correct this. More rigorous policies will mean that tutors will have to declare any vested interests when marking work or supervising students. Some universities, such as Manchester and Cambridge, now provide access to anonymous online reporting of harassment. However, as critics have rightly pointed out, anonymous reporting does not amount to formal reporting, and thus is of limited value as evidence. The real changes that need to be made are in access to formal reporting and in the degree of seriousness with which this is taken. A 2015 Association of American Universities survey of 27 campuses found that only 7.7% of sexual harassment incidents were reported, despite nearly one in six female graduate students claiming to have experienced sexual harassment from a teacher or adviser.

The highly competitive environment of academia can also serve as a cover for staff-on-staff, as well as staff-on-student (and, occasionally, student-on-staff) bullying. At the University of Glasgow, for example, definitions of bullying in academia have been usefully widened to include overbearing supervision, setting someone up for failure with impossible workloads and deadlines, exclusion, constant criticism or ridiculing and blocking career progression. One might add failure to accommodate flexible working for parents – friends tell me that universities often only pay lip-service to work-life balance policies. Work continues to be done on making people aware of unconscious bias. For example, a 2016 study of gender differences in recommendations for postdoctoral fellowships, published in Nature Geoscience, concluded that female applicants are only half as likely to receive excellent letters versus good letters compared with male applicants ‘at a critical juncture in their career’.

The large proportion of those working in the UK art world on a self-employed or precarious, zero-hours basis are especially vulnerable, having fewer rights than employees and being dependent on maintaining a blemish-free reputation. Artists, freelance curators and small-scale gallerists (particularly women) report being vulnerable when out on their own with potential clients. How to establish boundaries? Who to complain to when, as a young artist, a ‘collector’ invites you back to their home, only for his interest to have nothing to do with your work? People just shrug: what did you expect? Artist Celia Hempton tells me she is frustrated that some men mistake the sexual subject matter in her work for an open invitation to make advances. That women should censor their art, and deny their own gaze and range of intellectual pursuits and desires, seems utterly hypocritical at a time when the (temporary) removal of JW Waterhouse’s Victorian erotic fantasy Hylas and the Nymphs from Manchester Art Gallery – an artist intervention conceived as part of a performance by Sonia Boyce – recently provoked such public outcry.

Many employers in the art world are not companies but individuals, some of whom view their responsibilities for managing their employees fairly as a drain on their time and resources. Many of us who have been treated poorly as freelancers – not being paid enough or at all, or being harassed or bullied – will opt to just walk away quietly rather than take legal action, resolving not to work for that person or company ever again, and perhaps warning others to avoid them too by word of mouth or social media. At the time of writing, a publicly viewable tweet warned booksellers to boycott a particular independent publisher, ‘a serial and serious abuser of women’. The art world is quick to denounce exploitation related to global capitalism and politics, yet is far slower to recognise and condemn the institutional, psychological, physical and emotional abuses perpetrated within its own ranks.

Moves to cancel and postpone exhibitions by alleged abusers feel like PR exercises in damage limitation and reinforce WANS’ criticism of the media only being interested in sensationalist stories. If the removal of Waterhouse’s painting was intended to provoke public debate about curating public collections, offering Post-it notes on which to write reactions surely restricted the nuances of that discussion: ‘Feminism gone mad!’ read one unsurprising note. Such headlines distract from the more serious work of removing barriers to equality and calling out abuse of power. If we continue to sensationalise sexual harassment, without understanding it in the context of wider inequality and discrimination, we risk isolating victims further by making it nothing to do with the rest of us, and perpetuating the culture of silencing the vulnerable.

Postscript: WANS has been subdivided into geographical groupings, and has been holding face-to-face meetings to discuss future action. The London group held an organisational meeting on 11 January 2018, which I attended, and planned a first public meeting for 27 February (after the deadline for this article). A second one is planned for 8 March, which will sync with meetings in cities around the world. I have been advised that women, trans and non-binary people who are interested in attending future meetings should email info@not-surprised-london.org for details and with suggestions of topics they would like to see addressed.

Jennifer Thatcher is a freelance writer and PhD candidate.

First published in Art Monthly 414: March 2018.