Books

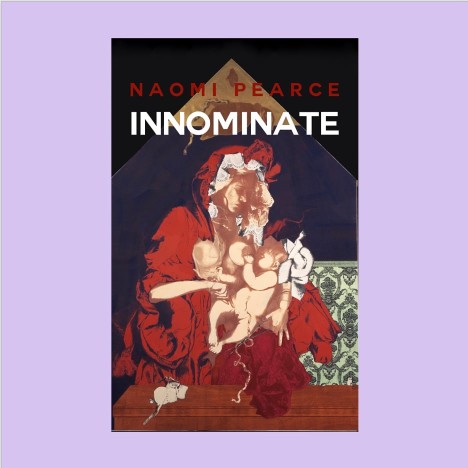

Naomi Pearce: Innominate

Jonathan P Watts on the forensic feminist methodology at the heart of an artist studio mystery novel

Naomi Pearce, Innominate

Innominate is a hybrid novella – part auto-fiction, part historical mystery – that is the culmination of seven years of research by Naomi Pearce into the undervalued and forgotten work of female administrators in London’s artist-led organisations of the 1970s. Set around a post-industrial factory in the East End’s London Fields, the novella’s structure comes from the layering of two sets of experiences in the same building across generations: Connie, who works in the shabbily converted artist studio complex as a live-in administrator, and who has to negotiate her own creativity in relation to gender, architecture and power in the mid 1970s, and Jane and Tam, a misaligned lesbian couple who move into the same factory 40 years later, now redeveloped into flats, allowing the couple both proximity to work and ‘unparalleled views’ of the park.

Jane, a self-made chef and working-class cockney, walks to work on nearby Broadway Market. Did her parents, when they worked the production line at the Bermondsey biscuit factory (the site, I wonder, of ‘Peek Freans’, once home of V22 studios), imagine that their daughter would one day run a celebrated restaurant? She is ambivalent about the gentrification around her, which she benefits from and certainly wants her slice of – in fact, she feels she deserves her slice.

Tam is a picture editor who works from home and barely leaves it. A confessed professional manipulator of affect, she is, however, helpless against bouts of anxiety and depression that intensify in the factory apartment. While aspects of the building’s heritage lie at the surface – incisions in concrete made by the grinding beat of machinery – the residue of bodies, their dust and hair are compacted in the cavities. What else is here? She attributes her depression to unseen toxic particles contaminating the building’s fabric.

Pearce deftly controls an atmosphere of something ‘not quite right’ – a hallmark of the mystery genre – to produce a paranoid reader who seeks a missing key and who grasps for ominous portents to the plot. This not quite right atmosphere includes the machinations of gentrification in 2017 and the diffuse patriarchy Connie encounters in 1975 at every turn along the studio corridors. It invites a reader to imagine how things might be historically righted, but it is also a way for Pearce to negotiate the unsaid violence of the past and present.

Pearce does – spoiler alert – eventually give the reader a body, even if there is no ‘intentional’ murder as such. While undertaking grimy DIY work in the flat, Jane recovers the petrified corpse of a baby wrapped in painter’s rags. We learn it is Brenda’s child, an artist who 40 years earlier had been raped as a minor by an artist in the studio complex. Brenda gives birth in his studio and his negligence and inaction results in the baby’s suffocation. Implicit is his unquestioned right to live as an artist, while female creativity is continually thwarted. The male artist cleans up and moves on, absolving himself of moral responsibility. Due to complications after the birth, Brenda dies through blood loss on the top deck of a Bethnal Green bus.

Between chapters Pearce describes with dispassionate medical precision the materiality of human bone formation, a ‘bone index’. These descriptions, she explains, provide a backbone for the story; indeed, the book’s title, Innominate, has two meanings: that which is not named or classified, and either of the two bones that form the sides of the pelvis. In her influential 2008 essay ‘Venus in Two Acts’, Saidiya Hartman, commenting on slavery archives, writes that ‘to read the archive is to enter a mortuary’. Thinking with this idea – mindful of the difference between racial capitalism’s eradication of lives and the lives of her interviewees – Pearce wondered if reading a mortuary might allow her to enter the archive. During her research, Pearce observed and meticulously described human dissection to advance what she calls her ‘forensic feminist methodology’. To the forensic pathologist, for instance, blunt force trauma to, say, a pelvis could be the key to unlocking a story and ultimately to finding justice.

From 2016 to 2020, Pearce carried out interviews with artists and administrators who lived and worked in London studio buildings clustered around Butler’s Wharf in Tower Bridge, The Dairy in Camden and various SPACE studios, including St Katharine’s Dock in Tower Hamlets and Martello Street in Hackney. Enduring the city’s thorough redevelopment, this last location still provides studios for artists, and among Pearce’s interviewees are younger female studio holders. Lost to developers, however, is Woodmill, an artist-led studio and gallery building in Bermondsey that Pearce co-founded and administrated for five years from 2009.

The vividness with which Pearce evokes the fictional studio building comes from time spent in these ruinous spaces. There is in Connie, perhaps, a cypher for Pearce’s experiences, but Connie is more than one single individual. Connie is a composite character. She never existed and yet, as Pearce writes, her struggles are real. She is the embodiment of intergenerational allyship. Connie’s character builds on the experience of the actual live-in administrator of Martello Street studios, Shirley Read, who Pearce interviewed and wrote about in the publication Continuity Girl (Unbidden Tongues #7, 2022). Connie also bears aspects of Letty Mooring, administrator of the Artists Information Registry from 1969–72 (and former managing editor of Art Monthly). The registry was a pre-internet index of artists which Pearce wrote about in the 2018 book Artists in the City: Space in ’68 and beyond (Books AM419).

A forensic feminist methodology has been applied in a further case study of Rita Keegan, who co-founded the artist-led Brixton Art Gallery in 1982. Pearce joined the Rita Keegan Archive Project in 2018 and, together with Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski, Lauren Craig, Gina Nembhard and Keegan herself, curated the exhibition ‘Somewhere between here and there’ at South London Gallery in 2021. Pearce also applied this methodology in her 2022 Matt’s Gallery installation ‘Almost Conceptual’, which was ostensibly about the founder-director Robin Klassnik but as seen through the experiences of another administrator, Helen Kalkhoven Dickson.

Innominate’s characters and events are a fiction abstracted from actual people and places. It is not ‘good’ art history, but where there is paucity in the archive we might, following Pearce, need to readjust the magnitude of our gaze, to get forensic. What can fiction do? ‘Fiction’, Pearce writes, ‘doesn’t force its sources to go public, it accommodates multiple points of view, the human and the nonhuman; it lets bricks speak. Fiction encourages complex, complicit characters, shifting between the intimate and the procedural. It can tell you what she’s thinking. It can make the bad guys pay. Or not. Maybe they never do. Fiction might be the only retribution available. Fiction feels able to bear the weight of my demands for history to have been different.’

Coupled with her forensic feminist methodology, fictioning is a powerful and productive approach put to work with impressive results in Pearce’s debut novel.

Naomi Pearce, Innominate, Moist Books, 2023, 160pp, pb, £12, 978 1 913430 14 6.

Jonathan P Watts is a tutor in contemporary art practice at the Royal College of Art, London.

First published in Art Monthly 469: September 2023.