Interview

The Artist is Present

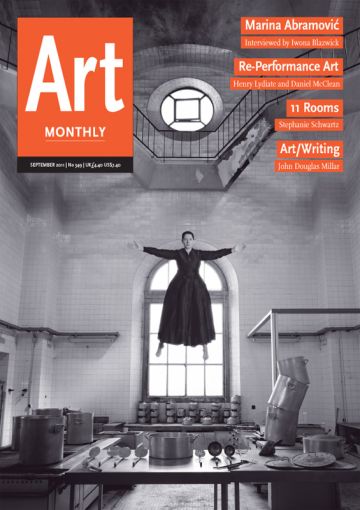

Marina Abramovic interviewed by Iwona Blazwick

Marina Abramovic The Artist is Present 2010 MoMA New York

Iwona Blazwick: I want to go back to a moment in Belgrade when it was still part of Yugoslavia. I wanted to start by asking you about a radical move that you made as early as 1970 that was a response, in a way, to the prevailing ideology in communist Yugoslavia of Socialist Realism. You proposed a realism of a different order. The first work I wanted to ask you about with regard to this is called Cloud and Shadow. What was the origin of this work?

Marina Abramovic: I was living in this really political, communist environment and, in 1968, during the student demonstrations, we were given this student cultural centre as a kind of present from Tito so that we could start doing experiments and try to figure out some other way of seeing art. The director of the institute invited us to bring in something that inspired us.

In those days I was painting clouds and I brought in this peanut and just pinned it to the wall and called it Cloud and Shadow. Another person brought the door of his own studio because there is something inspiring about opening the door and going in to make the work. Somebody else brought his own girlfriend, saying: ‘I always make love to my girlfriend before I make the work.’ And so on. It was a really important show. It was in 1971 and the title was ‘Little Things’.

IB: I know you were part of a group – another member, for example, actually taped you to the floor ...

MA: Yes.

IB: This was, for me, a kind of paradigmatic moment where you see the idea of the artist’s body as both subject and object. Another aspect of your work which comes out over and over again is the idea of removal, a kind of freeing or evacuation of something, for example in Freeing the Horizon. Can you tell me something about this work?

MA: First of all, I really felt like I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. I felt really suffocated. I had an idea that I’d like to travel – though I could not actually go anywhere – and so I would take photographs of different parts of Belgrade and then make slides and literally paint the buildings away – freeing the horizon – so that I could see as far as the eye could see.

At the time, in 1973, I made an installation with these works using eight slide projectors to create a 360° panorama of Belgrade without buildings and the most striking thing is that, 35 years later, because of the American bombing of Belgrade some of these houses actually no longer exist.

IB: The Airport is also, perhaps, a work about a kind of leaving, a fantasy about potential destinations.

MA: This work also took place at the Culture Centre. There were six artists – I was the only woman – and we were there every day, trying to work. One of the spaces was this big hall where I created this kind of utopian airport. I put speakers with the sound of my voice, very cold and very distant, saying: ‘Please, all the passengers of the Jat (the Yugoslav airline) airline go immediately to Gate 345 (in those days we only had three gates, now we have seven) the plane is going immediately to Tokyo, Hong Kong and Bangkok.’ Every three or four minutes this voice would remind you that you could go on this imaginary journey.

IB: We’re talking now about the realm of the conceptual. I think that, throughout your work, this idea of immateriality has been a very important aspect of what you do. Having left Yugoslavia – now you are travelling – you moved to the Australian desert near Ayers Rock. Can you talk a little bit about the experience of being there, and about living in a non-western kind of society or community?

MA: When I left Yugoslavia I was 29 years old and I literally escaped. Until then, all my performances were very difficult and physically and mentally consuming. I had to do everything before ten in the evening because by ten I had to be home because of my mother’s iron discipline. When I eventually escaped she went to the police to announce my disappearance, and the police asked, ‘How old is she?’ and when she said, ‘29’, they said: ‘It’s about time.’

First I went to Amsterdam and there I met Ulay, the person with whom I made performances for 12 years. The end of the 1970s was somehow the end of performance art – the galleries, the dealers, the museums – they just could not actually deal with something that was so immaterial like performance. There was nothing to sell and there was real pressure on artists in those times to create objects, to create paintings, to create – you know – things. I and Ulay didn’t feel like going back to the studio to make anything two-dimensional, so we decided to travel. Buddha went to the desert. Mohammed went to the desert. Moses went to the desert. Jesus Christ went to the desert. They all went as a nobody and came back as a somebody – so we were definitely thinking it had to be the desert.

We went to the Thar Desert, to the Sahara Desert, to the Gobi Desert and to the Great Australian Desert. We spent one year living with the Aborigines – literally without any money – with different tribes and moving through Central Australia and the Northern Territory. This was the most important and life-changing experience I ever had. First of all, we were confronted with a nomadic culture that doesn’t have any possessions, they just move as the songlines move – from place to place. Their’s was the most immaterial culture I have ever encountered and they influenced our way of thinking about performance.

IB: One thing that is striking is that it seems to coincide with an impulse in other artists at that time towards the idea of land art – not only going to the desert to escape the white cube but also to escape certain aspects of western society. The other aspect, I think, was the allure of alternative ways of being, of other societies, which seemed to coincide with a kind of anxiety about the affluence of consumerist society and so forth – the Beatles going to India, for example. How much did you feel that you were part of a bigger impulse?

MA: I don’t know. Coming out of Yugoslavia I did not know about the Beatles or the Rolling Stones – I was listening to Bach, Mozart, Brahms or Russian composers, so I wasn’t really aware of this impulse. To me, going to the desert was really about looking for ways to take performance beyond physical limits. At the end of the 1970s, my generation of performance artists – from Chris Burden and Dennis Oppenheim to Gina Pane – had stopped performing. They were making objects or dealing with architecture or painting, but not performance, whereas I felt that performance was far from over. I was looking for different ways to use the body and to push it beyond the limits of our culture.

IB: To get back to the idea of ‘nomadism’, you were living in Amsterdam in a van – in fact you even made works with this van, did you not?

MA: Yes. It was not like an American luxury camper van, it looked like a sardine can. It was a French police type of vehicle with no heating, no bathroom, nothing. I mean it was just a box – and second-hand at that. You could hardly live from performance work, but by living in the van we didn’t have to pay electricity and we didn’t have to pay rent, and if we needed gasoline we just cadged it with an empty mineral bottle from the gasoline station – we lived in the countryside and I knew every bathroom in every gasoline station in Europe where we could wash. It was really a happy life because we didn’t compromise. We were taking risks not just in the work but also in our way of life.

IB: Also, I suppose, you could never predict what was going to happen the next day or who you would encounter – so that must have been part of the risk-taking.

MA: Totally. After we sold the vehicle at the end of the 1970s to go to the Australian desert, we completely lost track of it. Then, about ten years later, we were approached by Paul Schimmel, the curator of MOCA, Los Angeles, who was working on the exhibition called ‘Out of Actions’. He wanted to include relics left over from performance art, like the golden nails Chris Burden used when he crucified himself on the Volkswagen, and he came to see us in Amsterdam and asked, ‘Where is that vehicle?’. We didn’t know, but he put in some work and traced it to the south of France – somebody was keeping chickens inside it. So we had to clean this car of chicken shit – which is very difficult – and bring it to Los Angeles. When I had my retrospective at MoMA last year, this vehicle was there and its arrival was very emotional for me. Our entire life was captured in this piece.

IB: A very profound aspect of your practice is the idea of time and duration. I wanted to ask you about the shortest piece and the longest piece. The shortest piece – I believe it lasts four minutes – is Rest Energy, first performed with Ulay in Ireland in 1980.

MA: Yes. I have made two pieces in my life that were most dangerous for me. The best pieces are the ones where I’m not in control. In the one called Rhythm 0 the public was in control – they could do whatever they wanted with me. The other one was this piece which was based on trust – if either of us lost control, the arrow would go straight into my heart. It was simple. We held the bow and arrow with our weight until we really could not hold it any more. We had to release at the same time.

IB: Rhythm 10 is also a very simple work where you ended up cutting yourself quite seriously. This idea of risk – of pain – has been a consistent element in your work. What do you think motivated that work?

MA: This was very different because I was not risking my life. In Rhythm 0 there was a pistol with a bullet and people could have used it if they wanted to, and in Rest Energy there was the bow and arrow.

Dealing with pain is an interesting subject. We are always afraid of pain, of dying, of suffering – the main concerns of human beings, basically. Many artists deal with this theme in different ways. I was always interested in how various ancient peoples worked with this in ceremonies – the ritualisation of inflicting a large amount of pain on their bodies – even to the extent of being clinically dead. The reason for this is not to do with masochism. The reason is very simple: to confront pain by taking this kind of risk in order to liberate yourself from fear and, at the same time, to jump to another state of consciousness. That is a really important thing.

I could never do this in my own private life, but if I stage the situation in front of an audience – and the staged situation is dangerous – I can take energy from the audience and use it to give me strength to go through that experience. So I become like your mirror. If I can do this in my life, you can do it in yours, and through that I liberate myself from fear.

IB: One thing I hadn’t understood is that something as simple as sitting very still for a long period not only involves endurance but is also very painful. Your most recent work, The Artist is Present, which you made for your retrospective at MoMA in New York in 2010, is your longest piece, is it not?

MA: One other piece was the same length – Walking the Wall. Ulay and I walked the Great Wall of China from two different ends to say goodbye. But in that piece the audience was not present, which is a very different matter. For the MoMA piece the audience was present and the situation was extremely simple. In the first two months I had a table and two chairs, then in the last month I actually removed the table and left just the two chairs, and that was it. It was a very simple structure. The idea was to sit motionless during the entire time that the museum was open – seven hours a day and ten hours on Fridays. The museum only closed one day a week – Tuesdays – and that was my free day.

IB: At the beginning, I think, there were the expected number of people but over the final weekend there were 20,000 participants – it was extraordinary. There were 850,000 participants in total. It seems that, given a lived reality which is often virtual – Facebook, social networking – and the frenetic nature of everyday life, this idea of actually connecting with somebody, and being asked to do something as simple as sit and look at the face of a complete stranger, somehow really spoke to people.

MA: You know, to me the most important thing is to do with how the public is always perceived as a group. We never perceive the public as individuals. This was an opportunity where everybody could have a one-to-one experience with an artist, and this really makes a huge difference.

It was also very important for me to deal with the museum atrium which is really the most difficult space because it is in permanent transition – people are moving from ground floor to second floor to different types of galleries, and there is also a library and a coffee shop – so there is nothing but a kind of hectic feeling of movement. It is like a tornado. But in every tornado there is a stillness in the middle – the eye of the tornado – so I tried to make this eye of the tornado the stillness of that moment of sitting.

IB: It must require a lot of training – I mean, all of your performances require a great deal of preparation even though they look intuitive and spontaneous – but to be able to endure sitting in a chair for seven hours must be tremendously punishing on the body.

MA: When you do any kind of artwork – or work generally – I think you have to put in an enormous amount of preparation, but the results have to look effortless. That’s the magic of it. It really looks like – well, here I am just sitting, what is the big deal? But it was hell, literally hell. If you just try it for yourself, sitting motionless for three hours, you will find that already after an hour and a half your muscles will want a change and you get this incredibly painful feeling that in one second you are going to lose consciousness. And yet you still don’t move – willpower is very important – you keep still, not moving, and that’s when something really interesting happens. When the body understands that you’re not going to move, the pain disappears and you really start having an out-of-body experience, which sounds mystical but it’s true. You leave the body. But then the pain returns again, but you just have to keep going. For two years I trained for this piece, like NASA trains astronauts. You can be trained physically, just like for the Olympics, but if you don’t have the determination or willpower you can’t do it. The mind is the biggest obstacle to everything.

The idea of this piece was to be in the present – absolutely in the moment. Not in the past which has happened. Not in the future that hasn’t happened, but just in that moment. Your mind doesn’t go anywhere else. You are in the here and now – and not only the here and now in myself, but also in the person sitting opposite you. It was amazing what happened to people. They came to sit opposite me – I didn’t limit the time – and they would become anxious, or they would become angry because they had had to wait for a long time or they would become suspicious or timid or self-conscious. Then, after a while – maybe six, seven, eight minutes – they would enter this zone where sound disappears, I disappear. They become the mirrors of themselves. And these incredible emotions surfaced – I heard so many people crying. The last month was the most difficult one, when there were just two chairs and nothing else.

IB: Why did you remove the table?

MA: There were many people in wheelchairs so, to accommodate the people in wheelchairs they would remove the chair. In the middle of looking at this person, I figured out that I didn’t even know if he had legs or not. I just saw his eyes. I felt that I didn’t need the table, I didn’t need the structure. So I decided on 1 May to remove the table. But the strangest thing was that, after removing it, I still saw it like a grey shadow. It was as though I was going crazy, but I realised that when you are in stillness an entire parallel world opens up to you which is normally invisible because we’re always moving. When you get into this stillness you start feeling things you could never imagine feeling normally. And the public started feeling what I was feeling. Why was it so emotional? I can’t explain it to you. You have to experience it.

IB: Has MoMA captured the anecdotal reaction of the sitters?

MA: One of the most moving experiences for me was when the museum guards came on their free day to wait in line to sit. The longest time a person sat there was seven hours, and then he came and sat another 21 hours. There was also a group of 75 people who sat more than 15 or 20 times with me. There was a group of people who met once a month. There were people who didn’t have any idea what is a performance, who don’t even like performance, who came to the museum like tourists come to New York – just to see it – and something clicked for them and that really matters to me. You know performance really has this kind of power to change not just the performer’s life but also the one who is witnessing the performance. I truly believe that only long durational work has that kind of power because if you do a performance for one hour, two hours, five hours – you can still pretend. You can still can act. You can still be somebody else. But if you do something for three months, it’s life itself.

IB: I suppose also the structure of the two chairs – the one facing the other – one could read it as being in some way sculptural or domestic, but one can also read it as a mirror of psychoanalysis. Does that interest you, the idea of a therapeutic encounter?

MA: You know, performance can be seen in so many different ways. Of course there’s a therapeutic element. I always believe that a good work of art has to have many layers of meaning. It can be political. It can be social. It can be spiritual. It can be just a sculpture. There are so many different ways that it can be taken by every person who experiences it.

I also believe the context in which you do something is very important. If you bake bread, however good it is, you’re still the baker who makes the bread, but if you bake this bread in the gallery – like Joseph Beuys – it becomes art because the context has changed. So I really believe what I’m doing is art.

Finally – after 716 hours of performing – they removed the chairs and there were just little crosses on the floor that marked the spot. Later on people came and started kissing the floor as though they were visiting Lourdes – I don’t know what happened. It was overwhelming.

IB: I want to talk about some of the very sophisticated aesthetic strategies that you use. Your use of systems and seriality, for example, in works like Rhythm 0, Rhythm 1, Rhythm 2, Rhythm 3. At the same time there is an absurdist element and a poetic element, especially in some of the titles. For example, Nightsea Crossing is a work which I would say was a prelude, perhaps, to The Artist is Present where you and Ulay sit opposite each other across a table. In Boat Emptying/Stream Entering there is this idea of symmetry and of a negative and a positive. Then there is The House with the Ocean View, a performance piece that you made at the Sean Kelly Gallery in which you lived inside the gallery, an idea that relates to The Artist is Present, whose title is taken from the convention of the private view card.

MA: For me the title is incredibly important. I always believe that when an artist puts Untitled on a work, it is like leaving children without names. I don’t know how you can do that. I really love titles. The Nightsea Crossing title was a really important title. It is not about crossing the sea by night, but about a subconscious crossing.

Boat Emptying/Stream Entering was made after Walking the Wall. It was like ending one period of my life. It is like when you have so much luggage on the boat that it will sink. What you have to do is throw everything out and only then can the boat take you to safety. So that was really a way of marking the change in my life and my work.

The House with the Ocean View was this long durational performance of 12 days without eating, just observing the audience and living in the gallery. Of course there was no ocean – the ocean was the public. That was the idea. The Artist is Present is literally like when, in the old days, you had an opening of a painting show and it would say that the artist would be present for the opening. I really was there for three months. I was present.

IB: The use of colour is very important to you, particularly in a number of tableaux that you made in the 1980s. Could you say something about that?

MA: In the early works – in the early 1970s – everything was black and white. In the 1980s we paid a lot of attention to colours and the meaning of colours. We studied the Vedic square and how colour changed you. We had this experiment: we took seven pairs of white trousers and seven pairs of white shirts and we just coloured them in the washing machine because it was too expensive to buy new ones. Then we would wear the bright yellow one month, the bright green one month, the bright red one month – all the spectrum of colours – and see how our behaviour changed. It was very interesting. Yellow is the colour that really works on your nervous system, you become completely nervous and crazy – that’s why they use it in advertising. Blue calms you down. Green – everybody talks to you when you wear it because it’s a communication colour. And so on.

Then we went much deeper into a sense of colour. In Modus Vivendi: Pietà, for example, Ulay is in white and I’m in red. In Chinese mythology – ancient Chinese mythology – the world was created by a red drop of menstrual blood and a white drop of sperm. We used this element in our work for a long time – the white and red.

In The Artist is Present I wore three colours. During the first month it was blue, the second month red and the last month white. All three colours have to do with energy – I really needed to calm down to get into the piece with the blue. By the middle of the piece in April the energy level was so low that I had to get energy back, and so it was red. White was very much to do with a complete purifying feeling at the end of the performance.

IB: Geometry is another unexpected aspect of the work. Could you talk about your use of the star, in particular in Lips of Thomas?

MA: I think that geometry, generally, was very much in our work, especially the early work. It was very important to me how things looked in a space and how they worked with the architecture – not just outside but inside with the architecture of the body.

The five-point star I cut on my stomach when I was in Yugoslavia was not the Jewish star, it was the communist star. I was born with that star, it was on my birth certificate. It was on every book at school. It was in every celebration of communism. It really was something that I felt that I wanted to get rid of – that symbol.

I cut two stars on my body, though you just see one. The first star I cut had two points at the top, which is actually the negative aspect of the pentagram. Twenty-five years later I cut another star with one point at the top. Somehow these two stars neutralised each other and so I was free from the concept.

In another early work, with Ulay, Duration Space, which we made for the 1976 Venice Biennale, we used our bodies in a very minimal kind of way, though it was still in an architectural way. It deals with two bodies passing and colliding with each other. The idea was how two energies – male and female – can come back together and make something that we called ‘Dead Self’.

We were also invited to make a performance at the Bologna Modern Art museum, and we had the idea of the artist as a ‘door’ because, if there were no artists, there would be no museum. So we became a door, and when people entered they had to make a choice: left or right. We were supposed to be there for six hours but after three hours the police arrived and asked us for our documents, but as we really were naked we had no passports to show them.

IB: That symmetry is seen again in Light/Dark of 1977.

MA: We only used one hand and we slapped each other as fast as we could – slow at first, then as fast as we could until we could not increase the rhythm any more. Again, it is a very simple structure using the body as a drumming element with amplified sound.

IB: Another iconic piece that again has to do with this idea of symmetry is Relation in Time, also of 1977.

MA: This is an important piece because we had 16 hours without the public and then, when we were at the end of our energy, the public arrived. We took energy from the public to enable us to sit one more hour – making it 17 hours in all. Normally we would take a performance to the point of exhaustion and then it would be finished, but here we actually got to the point of exhaustion before the work was completed.

IB: Do you want to say something about the work to do with the levitation of Saint Teresa in this context?

MA: I love this piece. I just found, in the north of Spain last year, the abandoned kitchen of a monastery where the nuns made food for 8,000 orphan children. It was abandoned in the 1970s. I decided that I wanted to make this levitation dedicated to Saint Teresa of Ávila because I was fascinated by her personality. I read her memoirs and many people in her time believed that she really could levitate. In her diary she talked about levitation. One day she levitated many, many times in her church while praying to Jesus. When she went home she was very hungry and wanted to make soup before taking a rest because she could not stand any more of this levitation. But, in the middle of making this soup, she found that she could not control the divine power which took hold of her again and she was so incredibly angry because she couldn’t finish her soup! I love this disadvantage of her divine power.

IB: One of the key aspects of performance is that its longevity depends entirely on documentation. You have made a very important decision, I think, about the way that your work is documented. Can you say something about the filming of this particular work?

MA: Up to 1975 I never filmed my work. There was no video at that time, especially not in Yugoslavia, nor was there enough money for any 16mm or Super8 camera – nothing. So the only documentation was done with a simple camera. But in 1975 I went to Copenhagen to do the performance Art must be beautiful, Artist must be beautiful and there was the possibility for the first time of making a video. It was the big new technology, but I didn’t know anything about it so I asked the man who was making the video to record the performance without giving him any instructions at all.

After the performance I was very eager to go to the backroom to see the material, but when I saw what he had filmed I was incredibly upset. He had used every possibility of the camera – zooming in, zooming out, looking left and right – it was not a document of my work. I asked him on the spot to delete his tape immediately and he did. Then I said to him: ‘OK, I’m going to do the entire performance right away, in this backroom, with only the camera – the camera is my public at this moment – you turn on the camera and please go out and smoke a cigarette.’ He did.

From that point on I understood the importance of documentation, and the importance of giving clear instructions to the photographer or cameraman as to how you want to present your work after the work is no longer performed. So this was a really big lesson.

IB: Bruce Nauman came to the same conclusion, as did a number of other artists who realised that it was not about making cinema, that it was not about theatre, and that it was not about drama – it was about making a completely indexical record of a performance or event.

MA: It is not about editing and cutting and all that stuff. It is just one forward shot – and, of course, in 1970s video it is always grey and boring. In the 1970s they made great performance work but the lousy documentation makes it look like shit. Whereas you now have great documentation of very bad artworks. The technology has developed so well that everything looks glamorous. But, when you’re talking about performance art, if possible you should always show the video material because it is still so much closer to reality than slides. A frozen slide is just mystification.

IB: Which leads into the question of re-performance and whether it is possible to restage a work – something we actually did at the Whitechapel Gallery a few years ago in ‘A Short History of Performance, Parts 1 and 2’. What does it mean to show a work that was conceived and made 30 years ago in the here and now? You took this as the subject of a work called Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim Museum in 2005 in which you actually re-enacted iconic works of art by other artists as well as your own.

MA: First of all, the reason why I did that was that I was so angry. Oh, God, was I angry! You know in all these years performance was nobody’s territory. Photography and video had been nobody’s territory but then they became mainstream art, but not performance. But now everybody – I mean everybody – was taking from performance. Even Lady Gaga – you name it – and without really referring to the original material. If you take a piece of music, or you take stuff from a book, you have to pay for it. And you have to acknowledge the composer and the author. But not with a performer. I was so angry with young critics who praised young performance artists doing things as though it was the first time ever when it was done so many times before that. My generation has really been damaged by that.

I felt that, as my generation of artists is almost not performing any more for different reasons – and I respect that – I felt it my duty to put things straight. This was my idea: to teach a lesson. And so I made this performance called Seven Easy Pieces. It was, of course, very metaphorical – Seven Easy Pieces was not at all easy to do. But I asked the artists – those who were living – for permission. In the case of those who were not alive, I paid their foundation for the permission. Basically, I respected the entire structure of each performance. The only change I made was the time I gave to each piece.

The first piece was Body Pressure, which was interesting because Bruce Nauman never performed this piece himself. He only had piles of paper which you could take home where you could read the instructions and perform it if you wanted. But I actually recorded the instructions and for seven hours I performed the piece.

The second piece I performed was Vito Acconci’s Seedbed, where he masturbates under the floor of the gallery. This one is very complicated because men produce sperm but a woman produces something else.

The next piece was Valie Export’s Genital Panic Machine – an open vagina with a machine gun. It is a timeless piece that can function in different periods, and I was really happy that she gave me permission to perform it.

The Gina Pane piece was very difficult. Her estate gave me permission to perform only part of the piece, the part where she lay on the candle bed. It was originally 28 minutes but I decided that I would perform it for seven hours.

The next one was Joseph Beuys talking about art to that hare. This was very complicated because his wife told the Guggenheim that she would never give permission. But if somebody says ‘no’ to me, it is just the beginning. So I took my suitcase and I went to Düsseldorf in the middle of the winter and rang her bell. She opened the door and she said to me, ‘Bravo, but my decision is still “no”. But you can have coffee.’ And I said to her, ‘But can I have tea?’ Five hours later I had permission. So that was Seven Easy Pieces.

Then came my retrospective. I thought it was very important that I choose five major historical pieces to be re-performed by young artists for the entire three months’ duration of this exhibition. There were 29 artists who re-performed these works in two and a half hour shifts – Point of Contact, Imponderabilia, Nude with Skeleton, Luminosity and Relation in Time. I didn’t give permission for any piece that would endanger lives or would injure the person.

Many artists are absolutely against the re-performance of works. But I’m very willing to give permission for re-performance. Performance is a live form of art, a time-based art, and if it is not re-performed – even without the original artist’s charisma, even if the piece is changed – it is still better than mere documentation in books or video.

IB: Do you acquire the rights to restage a performance piece or do you acquire the documentation for it? You have cited a number of artists as offering precedents as to how a collecting institution can acquire a work of performance – Yves Klein, for example.

MA: One of the most beautiful works by Yves Klein in the 1950s was when, on a bridge of the Seine, he sold The Artist’s Sensibility to his collector. The collector signed a cheque and gave it to the artist, and the artist took a match and burned the cheque and let the ashes fall into the river. So there was a kind of immaterial transmission of the artist’s sensibility. This was a wonderful act, I think.

The second one is Gino de Dominicis who, I think, is a really important artist. I knew him in the 1970s, when he sold Invisible Piece to a collector. This was a really interesting event that was very important to me in thinking about art as an immaterial kind of thing: the collector gave Gino the cheque and thought no more about it but, three weeks later, the collector got a phone call from a well-known transport company saying that they were going to deliver the invisible piece to him. He was very surprised, and asked when. They replied: ‘Next Wednesday at ten o’clock.’ So, the next Wednesday at ten o’clock the truck arrived with six people in grey coats and white gloves carrying Invisible Piece. When the collector opened the door they asked him, ‘Where are you going to put it?’ The collector said, ‘Next to the window.’ They said: ‘No, no, no. It is very sensitive to light. You have to put it somewhere else.’ And that was it. And now, so many years later, I went to see his retrospective at the MAXXI in Rome and the collector had lent Invisible Piece to the museum. I almost stepped on it. There was just a piece of tape on the floor and that was Invisible Piece right there.

Tino Sehgal is the only artist – he was an economist, by the way, before becoming an artist – that I know who has actually figured out a way of selling re-performing rights to a museum. He does it by whispering the instructions into the ear of the curator. The curator has to memorise it and if he leaves his job, he has to whisper it to somebody else. And this is how he sells his work. There have never been any photographs of his work.

Performing rights – that is the only way. But then you have to change the entire mentality of the collectors because, you know, the collector buys a painting, he puts a nail in the wall, he hangs his painting and he has it forever. But when you buy the rights to a work you have to choose the right person to re-perform it, and each time you have to pay for it.

IB: Can we talk about a future project, which is the Institute of Performance that you’re conceiving in America – in New York?

MA: Right now there is a hole in the roof that I’m going to repair from the money from the work we hope to sell from the show at the Lisson Gallery. The money will all go into this place. It is in Hudson, two hours from New York. It’s an old theatre built in 1936 – it can hold about 1,500 people. It later became a movie theatre where they showed regular movies, then it became a storage deposit for an antique shop, and now I’ve got it.

At this point of my life, I want to leave a legacy of my life. I want to make a centre for performing art, but also a centre for the preservation of performing art. This centre will address different types of art – not just performance as I am doing – but also dance and theatre and opera and music and video and film. The difference between this kind of performing centre and any other one will be that it will concentrate on long-durational work – nothing less than six hours – because I truly believe that long-durational work is the most important type of work right now. Because of the way we live, our lives are getting shorter and shorter, so art has to get longer and longer.

We also have to educate the public to see performance work that is long-durational, to experience something that is 20 hours long and where nothing much changes – maybe just the light. So that’s the legacy.

This is an edited version of an interview which took place at the Starr Auditorium, Tate Modern on 16 October 2010, part of the AM/Tate ‘Talking Art’ series. A video of the event is available at www.artmonthly.co.uk/events.

Marina Abramovic’s forthcoming exhibitions include ‘The Artist is Present’, The Garage, Moscow, 7 October to 4 December 2011; Galerist Gallery, Istanbul, October 2011; and ‘The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic’, Teatro Real, Madrid, April 2012.

Iwona Blazwick is director of Whitechapel Gallery, London.

First published in Art Monthly 349: September 2011.