Feature

Looping the Loop

Brian Hatton proposes a theory of the loop that predates its popular usage in film and video art theory

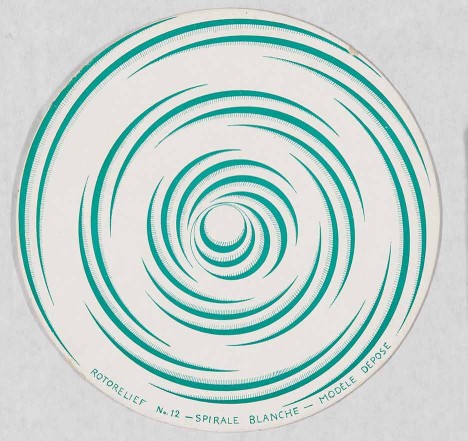

Marcel Duchamp Rotorelief – Spirale Blanche – Modèle Déposé 1935

Formally, aesthetically and even politically, the loop can be applied not only to recent art but also to modernist and mannerist art, and even to the Parthenon frieze. From Pollock to Parmigianino, from Dan Graham to Rodney Graham via Duchamp, artists of all stripes offer examples of phenomenal, literal and performative looping in art.

The term ‘looping’ has found wide usage in recent decades. In 2002 it was the theme of a big exhibition curated by Klaus Biesenbach for the Munich Kunsthalle of the Hypocultural Foundation and PS1 in New York, and there have been many variants of it, yet no general theory of looping seems to have emerged. To begin such an account, two ideas may be considered: one, that looping be regarded as a structural form that sets whatever is looped into intrinsic symbolic conditions, and two, that the literal looping devices used in recent works were already implicit in a ‘phenomenal’ looping in modes of aesthetic attention set by earlier mannerist and modernist art.

To take the circular format first, symbolic form is a longstanding strand in art theory. In English criticism it was made familiar by Clive Bell, who claimed that what supported aesthetic experience was ‘significant form’. Since Bell, formalist theory has turned more to structural and systemic considerations. The subject of analysis for Russian formalists was ‘art as such’, understood in Viktor Shklovsky’s essay ‘Art as Device’ as work wherein what was represented was bound into how it was represented, so that the how – in and through all of its devices – was integral to the work’s ‘content’ or import. Similarly, Erwin Panofsky’s Studies in Iconology based interpretation in an intrinsic fusion of image and means. Following Ernst Cassirer’s neo-Kantian 1924 opus The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Panofsky’s essay ‘Perspective as Symbolic Form’ proposed that people under different symbolic systems represent the world differently in their art so that the kinds of projection used in art each enact a ‘unifying principle which underlies and explains both the visible event and its intelligible significance, and which determines the form in which the visible event takes place’. In ‘Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures’, Panofsky went on to describe films as working ‘by the exploitation of the unique and specific possibilities of the new medium’, namely the ‘dynamisation of space’ and ‘spatialisation of time’. The ‘unique and specific possibilities’ of the medium as well as the appeal to Kant were likewise invoked in Clement Greenberg’s account of modernist art, located for painting in flatness, or rather, in the shallow space left in the absence of perspective. That apparently reduced latitude turned out through its very indeterminacy to afford new freedoms to painting’s optical and imaginative scope – enabled especially in cubism and abstraction. ‘Flatness’, Cubism and collage, then, might be described in Panofsky’s terms as ‘symbolic forms’. While this conjecture may conflate medium with modality, that may be an intrinsic premise of formalism. It is a conflation that perhaps has been conventionally assumed in the term ‘style’. There were parallels in architecture. Panofsky’s Warburg Institute peer Rudolph Wittkower brought to his Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism an approach that might be called ‘architectural iconology’, relating actual and implicit figures to ideas in Renaissance cosmology and music, and describing the circles and symmetries of central-planned churches in terms akin to Panofsky’s ‘symbolic form’. That those churches had not one centre but several on vertical axes was shown in a perceptive analysis by Robin Evans, ‘Perturbed Circles’, in his 1997 book The Projective Cast. A notion of ‘perturbed circles’ may be useful to an account of looping, but note how, in discerning those disquietudes, Evans shifted their impetus towards a condition – Mannerism – that prompted Wittkower’s student Colin Rowe towards his revision of modernist form, ‘Mannerism and Modern Architecture’. Rowe described both as effecting a perceptual restlessness within a confined zone. Wittkower had noted it across the facade of St George of the Greeks in Venice, but in ‘Transparency, Literal and Phenomenal’ Rowe discerned it also among the virtual or ‘phenomenal’ plays of actual/implied depth in the perturbed elevations and opened plans that appeared in architectural translations from Cubism.

Rowe’s analysis of ‘phenomenal’ transparency resembled Greenberg’s insistence on ‘flatness’, which drew on Hans Hofmann’s account of ‘push and pull’ among colour planes into and from a painting’s uncertain depths. They each described a restless to-and-fro in attention, a ceaseless scanning that found analogy in Jackson Pollock’s paintings. This cultivated errancy – first evident in the 18th-century cult of wandering, the picturesque and landscape gardens, then architecturally abstracted into ‘open plan’ – found concise summary in Kant’s account, in his Critique of Judgment, of ‘zwecklose Zweckmässigkeit’ or ‘purposeless purposiveness’, in which a disinterested beholding intrinsic to aesthetic experience reconciles understanding and imagination in a ‘free play of faculties’. Kant offered few examples, but we might infer from his analysis of ‘purposeless purposiveness’ a phenomenology of artworks that would sustain what we might call a ‘directionless attentiveness’. Within a bounded work, such aesthetic wandering cannot but reiterate, that is, recur without repeating, like a computer screensaver that never traces the same line twice.

The beholding of static images in artworks already involved looping, both in their scanning and in the feedback loop that held attention throughout contemplation and rendered a sensation, so often valued, of ‘arrested’ time; as on Keats’s Grecian urn: ‘Forever wilt thou love, and she be fair!’ – both the lovers’ stasis and the silence of ‘unheard melodies’ around them were held in orbit by the urn, a rhyme of the frieze around the Parthenon, itself an endless loop of the annual Panathenaic procession. There, space, time, image and music were brought into the loop of a single symbol. What both mannerist and modernist works did was to expose and intensify those devices of simultaneous recurrence and arrest. This was the estranged reflection followed in John Ashbery’s poem ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’, which circled Girolamo Parmigianino’s enigmatically calm tondo until it betrayed its secret perturbations: ‘– is this / Some figment of ‘art’, not to be imagined / As real, let alone special? Hasn’t it too its lair / In the present we are always escaping from / And falling back into, as the waterwheel of days / Pursues its uneventful, even serene course?’

In terms of repetition and recurrence, the literal repetitions deployed in recent looped works in no way resemble so-called ‘kinetic’ art, where movement or animation are valued in themselves. Looping, rather, annuls motion’s consequence, giving to time the undirected emptiness of space. Thus, Constantin Brancusi’s slow rotation of his sculptures wound contemplative space more tightly around them. Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Anemic Cinema’ (the near-palindrome is already a loop) works the other way. As the ‘Rotoreliefs’ revolve, they continuously swallow space and pulse it out again as endlessly inconsequent duration. They consume and occupy time, yet they do not conduct time as films and plays do. They share with looping a strategy: on one hand, negation of kinetic effects; on the other, avoidance of consequential narratives (plot, beginning, middle, end etc). Hence the German title of the 2002 exhibition, ‘Alles auf Anfang’ (Back to the Beginning), and films in it that rendered progress null and effort futile, such as Heike Baranowsky’s of a swimmer’s endless race and Carsten Höller’s of a carousel in almost imperceptible slow motion. Among these, Rodney Graham’s Vexation Island, 1997, is well known, but his earlier works show how he reached looping from serial Minimalism via a method (derived from Raymond Roussel, who also inspired Duchamp) of ‘interpolation’ – an insertion of a detour or delay (Duchamp’s ‘delay in glass’) into a discrete sequence. One example was a parody of a Donald Judd relief, with solids and voids alternating in inverse proportion, into which Graham inserted volumes of Sigmund Freud’s writings. Such a Judd relief was described by Rosalind Krauss in Passages In Modern Sculpture: ‘The same progression determines (but in reverse order) the size of the negative spaces between the elements. The visual interpenetration of the two progressions – one of volumes and the other of voids – becomes a metaphor for the dependence of the sculpture on the conditions of external space; for it is impossible to determine whether it is the positive volume of the work that brings the intervals into being, or whether it is the rhythm of the intervals that establishes the contours of the work. In this way Judd is depicting the reciprocity between the integral body of the sculpture and the cultural space that surrounds it.’ It was this ‘cultural space’ that Graham’s interpolations looped into the cases that he appropriated. The books subverted their formal integrity yet supplemented them by enjoining their implicit extensibility into literal/cultural space with topics on the mutability and instability of subjective space – Freud on dreams and repetition, Lewis Carrol’s Alice, Herman Melville’s ‘Piazza’ between reality and fairyland, and Roussel’s Impressions of Africa.

Of all Graham’s interpolations, the simplest loop was into Georg Büchner’s novella Lenz, where, finding that the words ‘through the forest’ appear both on the first page and repeated a few pages later, Graham attached the passage between the two occurrences to the second. As the passage describes a dreary journey among mountains, the reader is doomed to forever wander a wilderness, just as the novella’s Lenz never escapes his psychosis. To ‘can’ this looped time, Graham built a carousel for his readers, whereas his Parsifal (1882- 38,969,364,735), 1990, proceeded from a scroll that was built as a backdrop for the ‘Transformation Scene’ in Wagner’s opera. It depicted a forest through which Parsifal climbs to the Temple of the Holy Grail; as the singer barely moved on the stage, the forest scrolled slowly by. This was the passage where Parsifal declares: ‘Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit!’ (Here, time becomes space!) However, on finding that the musical interlude was not as long as the scrolling required, Wagner’s assistant Engelbert Humperdinck wrote nine extra bars to make time correspond to space. Discovering that this Ergänzungstuck (supplement) simply manipulated Wagner’s preceding bars into a loop that could be reiterated until Parsifal reached the Temple on the scroll, Graham introduced into them a system of epicycles, putting them into an iterative algorithm that so extended Parsifal’s ascent through the forest that he would not reach the Temple of the Holy Grail until some astronomically remote future. Thus, like Graham’s other interpolations, this loop did not reinforce but rather subverted any hope of formal autonomy. This ‘deconstructive’ turn in looping had already been initiated during the 1970s in the performative and video works of Dan Graham.

‘Looping’ entered currency during the 1950s to name feedback circuits in responsive, automatic and computational systems, following Norbert Wiener’s accounts in his books The Human Use of Human Beings and Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. In art, however, looping might be said to be a technique for control that exceeded control. It was implicit in works like Robert Morris’s Card File, 1962, and Box with the Sound of its Own Making, 1961, that used self- referential systems to ensure autonomy – or a simulacrum of autonomy, rather as Duchamp’s Readymades were simulacra artworks, for, like the Readymades, Morris’s self-defining circuits turned attention around to the situation of their encounter. Of such experience, Krauss wrote in Passages: ‘The shape of this moment has ... the character of a circle – the cyclical form of a quandary ... Turning back on itself, this inversion of narrative substitutes the strategy of a self-critical enterprise for the production of an outcome.’ Paradoxically, self-referential techniques resulted not in windowless monads but tools for interpolating social space. An example was Dan Graham’s 1966 Schema, which presented every time a list of its own specifics, but decided in each case by how and where its publishers printed it in popular magazines and journals – in Krauss’s terms, the ‘cultural space that surrounds it’. This was a loop, but one comprising an entire ambient topology that now included intersubjective time. Soon after Schema, Dan Graham’s essay ‘Subject Matter’ described Bruce Nauman’s latex sculpture as ‘topological’ and as initiating a feedback loop with the beholder: ‘Continuous transformation of image in such “rubber-sheet” geometry correlates with the spectator’s act of apprehension of the object via eye and body movements as the spectator’s visual field ... itself shifts in a topology of expansion, contraction or skew.’ In Nauman’s performances, Graham found this interaction intensified: ‘he plays the house ... audience members to body members to architectural member ... Everybody is shifting in relation to the kinaesthetic, visual, aural and informational totality of the process.’

Both Krauss in Passages and Alex Potts in The Sculptural Imagination stressed a turn in 20th-century sculpture towards experiential time in ways that implied modes of phenomenal or literal looping. Potts developed the term: ‘A basic sense of looping, of a potentially endlessly repeated, slightly variegated, circuiting is perhaps even more central to the temporal dimension of apprehending a work of art than it is to the experience of music. Most work which draws the viewer into its spatial ambit, and in effect makes the viewer into a performer, such as Nauman’s Going Around the Corner Piece, 1970, is structured to engage her or him in a limited repetitive sequence of bodily experiences and movements.’ In another 1970 work by Nauman, Corridor, visitors moved to see themselves on video screens at the end of a passage, but saw that as they advanced their image receded, for the screen was feeding back to them shots from a camera behind them at the other end of the corridor. Visitors entered a loop, but one which continuously displaced and decentred them.

Negations and evasions of closure link Nauman’s and Dan Graham’s attraction to looping to a moment when they turned away from objective strategies by which Minimalism had sought autonomy (grids, series) to address subjectivity and time. Looped film could ‘can time’ as Duchamp had ‘canned chance’, and audiotape looping offered poets and composers a way to ‘can’ sounds and phrases. Video transformed looping into not just a recorded but a performative medium in live time and social space. Scanning across objective arrays was turned 90 degrees to oscillate between object and subject, and, with Dan Graham, subject and subject. Eric de Bruyn describes in ‘Topological Pathways of Post-Minimalism’, published in the Fall 2006 journal of the Grey Room, how Graham’s move to subject-subject loops was influenced by topological social models advanced by the psychologists Kurt Lewin and Gregory Bateson, and the Radical Software writer Paul Ryan who ‘was convinced that the video loop provided the weapon to destroy all social hierarchies’. Ryan wrote in his 1970 essay ‘Self-Processing’: ‘The möbius strip provides a model for dealing with the power videotape gives us to take in our own outside ... The möbius video strip is a tactic for avoiding servomechanistic closure ... one can learn to accept the extension out there on tape as part of self. There is the possibility of taking the extending back in and reprocessing over and again on one’s personal time warp.’

Yet Dan Graham has never been a techno-utopian. His video works with feedback and delayed feedback, both in looped chambers like Present Continuous Pasts, 1974, and in social sites such as shopping arcades, were catalysts for existential humour as much as phenomenological experiments among self and others. Moreover, many loops that Graham has devised simply set up person-to-person exchanges. His brief for Past Future/Split Attention, 1972, simply states: ‘Two people who know each other are in the same space. While one person predicts continuously the other’s behaviour, the other person recounts (by memory) the other’s past behaviour.’ Among these interactive loopings, perhaps the most critically effective was Performer/Audience/ Mirror, 1975, in which an audience watches itself in a mirror, while a performer, standing between audience and mirror describes alternately himself and the audience. Gradually, this spoken and reflected feedback modifies the audience’s self-awareness, involved in a continually offered yet repeatedly displaced ‘now’. Yet, unlike Viktor Schklovsky’s ‘device’, its estrangement reveals nothing, loops or feeds back nothing but its own occasion. In the 1982 essay ‘Dan Graham and the Critique of Artistic Autonomy’, Thierry de Duve described this performance as an ‘allegorical fable’, the ‘political lesson’ of which ‘is that the production of a group imaginary – whether class consciousness or hippie conviviality – cannot result in a coherent vision of the world stated from a common viewpoint. And this is a severe critique of any political philosophy that remains captive to the autonomist ideal.’

Brian Hatton teaches at the Architectural Association, London and Liverpool John Moores University.

First published in Art Monthly 406: May 2017.