Report

Letter from Kampala

George Vasey reports on the Ugandan capital’s energetic but under-resourced art scene

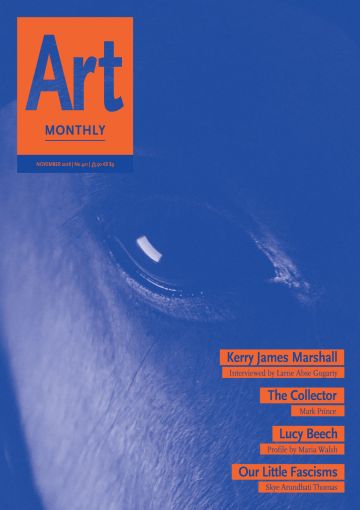

opening of Kla Art 18 – audience member views part of Timothy Wandulu’s 2018 video Modern Intellects

Kampala is a hectic city and, for a novice, a very difficult one to navigate with its lack of public transport and gridlocked roads. The ubiquitous boda boda motorcycles are often your only option for getting around. Writing a city report is fraught with difficulty and my impression of Kampala is fragmented and partial, formed in conversation with artists, curators and writers that I met during my visit. Kampala is Uganda’s largest city with – depending on who you talk to – around two to nine million inhabitants. My feeling is that nobody really knows, yet it is clear that the city is developing rapidly with an expansive programme of construction made possible by a loan from the IMF. There was much talk amongst artists about money coming into Uganda through tourism and Chinese business with little of it benefiting the country’s poorer communities.

Similarly, with little in the way of public support or funding, artists have been left to create their own opportunities and the art scene that I encountered on my trip, while small, was energised by a shared purpose. The College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology at Makerere University offers the city’s main art course with hundreds of artists graduating annually. I met Banadda Godfrey, one of the senior tutors at the college, who makes dense lyrical and surrealist paintings that address biblical themes. Like much of the painting that I saw, there was an attempt to merge a modernist lexicon with narratives and forms that felt natively Ugandan. Godfrey talked about the low esteem that an arts career was held in, in what is a largely agricultural economy. While art for most Ugandans felt like a luxury, he argued, there was a deep sense amongst artists of its ability to empower and enable communities.

This was exemplified by Tusiime Mathias, who spent a day taking me and a small group to visit local artisans, and enthusing about untapped opportunities for collaboration between makers and local artists. Mathias runs Uganda Community Art Skill Development and Recycling Arts Centre (UCASDR) from his home and he has ambitions to grow the project into a larger organisation that enables social cohesion for young people through a focus on art and sustainable practice. He has persuaded artists to gift him works that he hopes to sell to fund projects that bring together craft, recycling and art.

At the heart of much of the arts activity is 32 Degrees East, an organisation that runs residencies, exhibitions and workshops alongside professional mentorship and networking opportunities for artists across East Africa. Run by Teesa Bahana, the organisation has plans to enlarge its activities and build gallery and residency spaces in a new location for which it is currently fundraising. During my visit, 32 Degrees had organised Kla Art Festival around the theme of ‘Off the Record’, which brought together performances and events around the city. On my first day, George Harding from Open School East led a writing workshop and walking tour of Kampala directed by Deo Lubega from the Mountain Club of Uganda. It was the perfect start to my visit, providing a glimpse into the heritages and texture of Kampala’s distinct communities. As part of the festival, Graffiti Crew, a collective of four artists, presented the project Invisible Soldiers with murals made with female workers in the Katanga slums. Working alongside their collaborators over a prolonged period of time, members of the crew talked of creating positive narratives that amplified the voices of marginalised communities that are rarely heard.

One of the stand-out events during my visit included SoFar, a loose global network of events that are often announced at short notice. For the Kampala edition, a series of performances and poetry readings were presented at the Ham Mukasa House, which was previously the home of politician and diplomat Ham Mukasa. The British-born poet and writer Ife Piankhi delivered a blistering series of poems tackling her brother’s recent death and a move back to the country of her parents’ birth. Name-checking writers such as Toni Morrison, Audre Lourde and Alice Walker, Piankhi talked about a strong African feminist identity which echoed the texts of many of the other writers and poets performing and which was further dramatised by the potent context of the colonialist-era house. Piankhi was involved in other parts of the festival, working with Christine Ayo on Voicing Entebbe, a multifaceted project initiated by Ayo that explores violence against women. For Kla Art, the project culminated in a sound installation that travelled between the two cities of Entebbe and Kampala, forming a mobile monument to women who have been murdered and raped.

As part of Kla Art Fair I had been invited to host a workshop at 32 Degrees in collaboration with Newcastle University and the three-day event brought together artists from Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. It was a raucous affair with intense debate and discussion around working conditions. I was struck by how vocal each and every artist was, taking it in turns to stand up and talk around their own experiences. Artists shared grievances about the lack of critical engagement from local media but talked positively about the communality garnered by institutions such as 32 Degrees. There was much talk about the lack of visibility for a Ugandan art history due in part to the lack of a significant national and public collection. Perhaps because of this, there seemed to be little common ground and there was disagreement around the meaning of words such as curator, gallerist, dealer, writer and collector, which were often used interchangeably and to much collective chagrin.

In terms of the commercial gallery scene, Afriart was the leading player. Founded by the artist Daudi Karungi, Afriart challenges the lack of visibility and market for Ugandan artists and offers a programme of solo exhibitions annually. It has grown to encompass two gallery spaces as well as consultancy work and participation at international art fairs. Taking a holistic view on artists’ support, Karungi also established Start Journal, which provides critical interviews with profiles of artists from across East Africa.

Curated by Simon Njami, the Kampala Art Bienniale opened soon after my visit and ran through September, taking the atypical form of an apprenticeship programme offered by established artists including Godfried Donker, Myriam Mihindou and Pascale Marthine Tayou, amongst others. The mentors set up their studios in the city for the duration of the biennale and mentored East African artists. The concept was met with a certain scepticism by local artists; Njami is a divisive figure because of his claim in an interview that there is ‘no art in Uganda’. A little bit of googling brings up Njami’s qualifying appraisal that there is little infrastructure to support the scaling-up of production, and a lack of the kind of sales and commissions that are needed to sustain artistic practice. I found that many of the artists that I spoke with made very little money from their artistic practice, yet they supported themselves through an expanded practice making websites, illustrations and graphic identities for NGOs and businesses.

During my time in Uganda, the national news was dominated by pop star-turned- politician Bobi Wine’s imprisonment on seemingly jumped up charges of treason. Looped news footage of the police’s heavy-handed response to protesters painted a bleak picture. Wine hopes to replace the current autocratic president Yoweri Museveni and, as the self-proclaimed ‘ghetto president’, he has galvanised a disenfranchised younger generation. Around 77% of Uganda’s population is under 30 and there is a call for imminent and much-needed change. While my image of Kampala is partial, the city felt energised by young people who were eager for change and opportunity. I have a feeling that in a couple of years a future report would be very different.

George Vasey is a curator at Wellcome Collection and writer.

First published in Art Monthly 421: November 2018.