Interview

The Listener

Lawrence Abu Hamdan interviewed by Chris McCormack

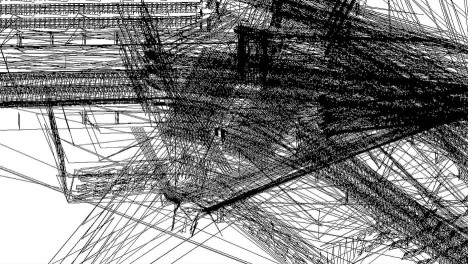

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Saydnaya (ray traces), 2017, detail

Chris McCormack: You refer to yourself as a ‘private audio investigator’. It seems that you use sound to either reveal or reconstruct traumatic experiences that have otherwise been rendered inaccessible. Indeed, your work is striking for its use of courtroom testimonies that you have given concerning forensically analysed sound files often produced in support of human-rights organisations.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan: That was explicitly the case for the Saydnaya prison investigation. My work has been a process of using, on the one hand, my technical training as a musician – as someone who studied sound – to create series of audio artefacts that we can listen to, and, on the other, my skills as an artist to produce interviews and dedicated series of what I call ‘ear-witness interviews’ that would try to create a language through which their acoustic memories could speak.

I do a lot of the sound work for Forensic Architecture, an organisation which is based at Goldsmiths University and which, with Eyal Weizman, produces investigations into human-rights abuses. So when Amnesty International approached us to help uncover the conditions of Saydnaya prison in Syria – the closest they could get was satellite images taken miles away as the prison is still operational and no independent observers have been allowed in – the only way to access this place was through the memories of survivors. The project demanded some new forms of representation to document the prison because it was so intangible. It felt like there was a need, after producing this comprehensive study and website for Amnesty, to give attention to how memory conjoins with architecture and violence. I returned to the material to make what I am calling ‘fragile truths’ – artworks that I am insisting be evidence.

These ‘ear-witness’ accounts of those held captive at Saydnaya prison – the site, according to Amnesty, of an estimated 5,000-13,000 executions between 2011 and 2015 of political prisoners under Bashar al-Assad’s regime – have led to the audio installation Saydnaya (the missing 19db) and the lecture Bird Watching, both presented at this year’s Sharjah Biennial, and now the drawings Saydnaya (ray-traces), which resemble expanded diagrams that map these experiences acoustically.

Why I got involved was because none of the witnesses ever really saw anything of their space of capture. They were blindfolded when they arrived, they were forced to cover their eyes whenever the guards were in the room, they really only saw the four walls of their cells. Unless they directly experienced it on their bodies, their entire perception centred on what was heard.

While conducting these interviews I built an image of the prison, which, with help from an architect, was modelled in real time. So, the processes of reconstruction and interview were entangled – it wasn’t like an objective study in which someone was asked a series of legal questions in an interview, but rather it was like a group project together with the witnesses to create and claw back some knowledge, by placing their mind’s ear in our mind’s eye, from this place in which everything other than the violence was hidden from them.

The audio installation Saydnaya (the missing 19db) refers to the incredible drop in sound levels or decibels recorded throughout the entire prison after 2011, rendering the enforced silence of the political prisoners somehow audible. Bird Watching, meanwhile, resembles a lecture, but one that is disrupted by discordant descriptions and memories which intersperse and interrupt the testimonials or attempted recollections from those incarcerated.

I am insisting on it being a body of evidence, but it is a body of evidence that focuses on silences, on whispers, on the distortions of memory, on the weird conflations between space and the body and the walls – on a whole series of things that emerged in this interview process, and this process of reconstruction, that does not yet have a language. It still cannot be fully explained.

In the ray-trace drawings you can see the obliteration of architecture as much as its construction. Indeed, the repetitive overlay of lines that comprise the ray drawings evokes redaction. Similarly, the video Rubber Coated Steel, 2016, consists of testimony provided by you that is redacted or visibly struck through.

The modest proposal for these drawings is to try to produce an image of incarceration that the prisoners were giving to me, one that speaks much more about sounds flooding in without control – the disorientation of where these sounds are coming from, how floors are vibrating or how they are connected in unexpected ways through water pipes. This image is quite different to the kind of imagination of incarceration that, perhaps, you or I would have had before – of a room with four walls which you are confined to – where visual limits are the way in which one feels the claustrophobia of incarceration.

Ray tracing is a tool for digital visualisation in architectural design that maps all the potential acoustic leaks throughout a building. By analysing a 3D model you can use ray-tracing software to predict how sound would propagate in any given design. Each line speculatively models the way a sound wave reflects off the walls, floors and ceilings to produce an architectural acoustic scan.

The drawings speak of a kind of structural violence, or the inseparable nature of the architecture and the violence and the acoustics of the violence that was done there. The idea that they are being struck through is interesting because, at some point, the acoustic reflections in a building start to phase each other out, or start to produce a kind of noise, or noisy image. There are moments when you can make out a staircase, right? But we are not looking at the staircase, and that’s what is interesting. So it is almost a coincidence that we can even see that it is a staircase. These small crossovers between the sensory experience, between the image and sound, mean that you have to configure your architectural understanding of what is in front of you, and at times just be overwhelmed by a kind of noise. Yet, these were people who were living in silence, so imagine 2,000 people all not being able to speak above the smallest imaginable whisper, a whisper you can’t even hear. This has its own sound, and it means that everything, even a pin drop, sounds like an explosion.

You describe in Bird Watching how one survivor recalls the dropping of a box of food outside his cell – after a week of starvation – at a physically impossible volume, and this reveals the intense hunger he felt. Throughout your work there is a sensitive insistence around the extremely variable conditions of audibility. You have spoken about how whispering acts in the hinterland between silence and noise.

I feel like the struggle in my dealing with the relation between politics and sound, or the politics of listening, is the negotiation of the ‘inaudible’ – as you see most explicitly dealt with in the video Rubber Coated Steel from 2016 – which is what stenographers write in square brackets on the page when they can’t comprehend the sound that is being made, or they cannot make it out. I’m interested in speech that does not make the historical record except in its very inaudibility.

My works return to the inaudible because it is this threshold of audibility that is equally the threshold of the political. It is those inaudible voices and sounds that are not yet intelligible to the political ear that become the site of struggle in the politics of listening. Much of my practice and my work as a ‘private ear’ is dedicated to expanding the political ear to listen past what has been labelled ‘inaudible’ in order to reconstitute its sound from its silencing and, at the same time, to amplify the structural conditions through which these inaudible sounds are unable to be heard by the forums in which they are supposed to receive a just ‘hearing’.

So, I want to operate within the realm of the inaudible or this ‘hinterland’, as you said, in order to refute its status as inaudible – to not be satisfied with silence and abstraction – and to listen so intensely to silence or to what is claimed to be inaudible so that it is no longer inaudible, so that it becomes a form of language itself.

The video and performance work Contra Diction (Speech Against Itself) from 2015 marries the technical apparatus of speech surveillance used in western societies to track and determine the origin of speakers’ backgrounds, the new software of ever-more sophisticated ‘lie detection’ programs, with the term taqiyya being used as a potential way of interrupting or overturning these present conditions of listening. Your use of the term suggests a mercurial vocal subterfuge – either masking an accent or modifying your language or behaviour – in order to make an imperceptible vocalised ‘passing’ in an exchange with another person that could otherwise result in a violent or even lethal situation.

Historically, taqiyya was used to recognise the preservation of one’s faith under the forced adoption of another – so, yes, subterfuge relates to this term. But rather than the freedom to say who you are and to have an identity – the freedom to be yourself – taqiyya is the freedom to use speech to become anything you want. Speech, in this regard, becomes a tool for the malleability of identity rather than as a manifestation of origin. Today, free speech and identity formations are being weaponised and, for me, taqiyya is some sort of antidote to that. So, yes, on the one hand taqiyya is a subversive act, but on the other hand – and this is why, in Contra Diction, I speak so much about code switching in speech – it is something that we all do all the time. Like now I am talking to you differently from how I would if I wasn’t being recorded.

Apart from being inseparable from cultural and political signifiers, technological advancements are shown in this work as being not only tools for listening, but also for pointing to the avoidance of listening, an avoidance that absolves or distances us from the task.

The conditions of listening and of recording are always in our voices. The technology, the listener, whatever is listening to us, totally reshapes the way in which we speak and that, for me, was what was also interesting about taqiyya, because the definition I was given and that I feel most closely explains why it is such an important legal right is that it speaks of the readiness of the other to listen.

The conditions of how we listen are given forensic attention in Rubber Coated Steel. Filmed in a shooting range, the video effectively weaponises even the process of looking: target posters are replaced with images that include the unique sound profiles, or spectrograms, of rubber-coated and live-round ammunition. The video centres on testimonies given in a case about the double homicide of two teenagers in Palestine by an Israeli bodyguard.

The projects emerged because the conditions of representation were so inadequate, and the means through which something like this could be brought to trial would have demanded a different type of ‘resolution’ that is unavailable.

So, how do we look and listen to this if the form of the trial is already compromised? And through that question you end up with a kind of equation which I hope is answered by the video and all the formal considerations that I am presenting. And so, to condense this equation: there were two different ways in which the body of Nadeem Nawara and the body of Mohamad Abu Daher were dealt with – they were the two boys who were killed. With Abu Daher, the second boy who died on that day, the family withdrew his body. They took it away, they didn’t want an autopsy. And that is considered religiously conservative by a lot of people but more broadly they don’t really understand it as a political position – how Palestinians have had to negotiate the limited forms of representation that have been made available to them.

So his family withdrew his body and they buried him. What happens then is, metaphorically, it becomes part of a colonial mass grave, right? It doesn’t become a single site of inspection, it becomes one more body dumped in a mass grave that speaks of a colonial violence that has been done to their people, and he becomes a kind of martyr. The body becomes a kind of collective subject.

So he doesn’t end up in a morgue where the body is scrutinised by the same authorities which killed him, who use that same image of scrutinisation as a means of saying, ‘Look, we are a democratic and civil society which investigates even our own violence’. And that is a very brave and strong thing to do, and passionate and amazing but, at the same time, none of that withdrawal can manifest itself properly unless you consider Nawara’s body. His father submitted his body to an autopsy despite massive criticism, despite having to listen to the humiliating accounts by Israeli authorities twisting the narrative of someone else shooting at the same place, and he has to sit and listen to things about his son who died that are simply beyond imagination.

Nawara’s father has put himself in a position where he is unpopular with his own people and, of course, not really getting anywhere legally because of the forms through which the legal representation happens – and that is perhaps even more brave.

So what you have are both things mobilised: the kind of silence and speech, the withdrawal, and a submission that is compromised within the frames of what is available to us to make justice happen. This kind of push and pull, withdrawal and reveal, is what allows the complexity of representation and what it means to unfold. Which is why it was necessary for me to write a fictional transcript of this trial and capture all these problems, to present the audio evidence – the sound of the gunshots that previously were never analysed – that now stand in for the body of Abu Daher, and how the sounds of these shots are presented in a context where the problems of listening are also there. So you use sound as a way to map the problems that we have of listening.

The camera moves with a disembodied smoothness. At the same time, the audio is hermetically silent, with the courtroom commentary recorded only in captions. The automation of the camera’s movements, to some degree, captures a sense of powerlessness at the unfolding description of violence.

The video follows a structure that I borrowed from a 1988 Harold Pinter play called Mountain Language, which is about a banned language in which you, as an audience, are watching this strange, bizarre, bureaucratic thing unfold in front of you: this prison scene where you just keep seeing people try to speak who are being banned. You as an audience member are always wanting them to speak, desperate to have the character use his voice – and then, at the end, the ban is lifted inexplicably and it is casually said, ‘OK, you can speak now’. And, of course, there is a silence in the face of this.

So again, a kind of shift – a simple shift – but something very clear about how the permission to speak is as violent as the banning of a language. In Rubber Coated Steel, the crescendo is not to finally hear the witnesses’ voices after they have been pushed out and redacted, but instead it is the prosecutor who keeps trying to bring the witnesses forward and who, in the end, implores them to speak, but all you have is a kind of inaudibility – I wanted to make a claim to that inaudibility.

As you say, this shooting range is the rehearsal stage for violence, it is also a place that becomes a container for those gunshots and suppresses them from the outside world. The idea of not seeing any people, of not having any voices – a kind of strange automated system of display – all these things start to be put to work in trying to bring a language to something that posits very complicated concerns about what are the politics available to us.

These testimonies, once overturned by the judge, are then visibly redacted and struck through on screen. Judith Butler describes the risk of the repeated picture of Palestinian devastation as compounding a sense of political paralysis which stops ‘viewers to judge and act’. I wondered how this video might propose a different mode of understanding of the oppressions that exist.

These voices are suppressed both because they are colonised voices and by their own volition, and I think that deserves listening to. Ultimately, this whole case was about listening to suppression. In very literal terms I was listening to the means through which a live ammunition was being disguised with the use of the suppressor to sound like a non-lethal rubber bullet. Therefore, an inaudible sound of a gunshot that is itself suppressed is only immediately audible to those whose voices are silenced, by both their own volition and by the refusal of the Israeli authorities to allow them to speak in court. Here we see that the struggle for audibility is presented as a complicated equation, one that cannot simply be solved by amplifying the voices of the unheard but rather by attempting to create a new language for the expertise and evidence while simultaneously respecting their will and status as unheard. Having lived through that investigation, the biggest lesson for me, in a way, is how as artists can we try to rethink those conditions, to use form and aesthetic practice to experiment with what politics can look and sound like, and to become this plastic form that is moulded out of the politics that it attempts to negotiate.

Would you say that you are attuning the viewer to a kind of perceptual or auditory vigilance?

I think there is an aesthetic training that we have as artists, an intensity of looking at the world so as to produce another kind of resolution. For instance, every video artist knows that the cable going in to power the video monitor is also part of the work. So as artists we are trained to think of the infrastructural conditions when making a work. For example, how often are artists told: ‘Oh, you’re the only one who notices that. No one who comes is going to notice that.’ I think there is something important about owning that position – that you are the only one who notices something.

Noticing, chronicling – these all become forms of resistance?

I see the role of the artist as documenting the world in an avant-garde way – a world that doesn’t yet accept these things as documents, but will, at some point. I’m reminded of Susan Schuppli’s new film Atmospheric Feedback Loops, in which she interviews Dutch meteorologists who are using early – pre-photographic – Dutch paintings of clouds as raw meteorological data to chart climate change. So what makes most sense for me as an artist now is to build on that, to believe that the forms of historical documentation and truthmaking we use today are inadequate, and to use experimental material and aesthetic practice as a means to produce new kinds of documents. This involves focusing often on what is in the background, the structural conditions, to propose a truth and to use the intensity of looking at and listening to the world and to posit a different kind of truth-production through art – a truth-production that is not the law, that is not science, that has very different kinds of models of defining what the truth is. I think art is a third way of doing that.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan has started a DAAD Fellowship, Berlin. Forthcoming exhibitions include the Gothenburg Biennial, and a solo presentation at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, spring 2018.

Chris McCormack is associate editor of Art Monthly.

First published in Art Monthly 407: June 2017.