Film

International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam 2024

Rachel Pronger discovers how the IDFA attempted to recover from the previous year’s calamitous festival

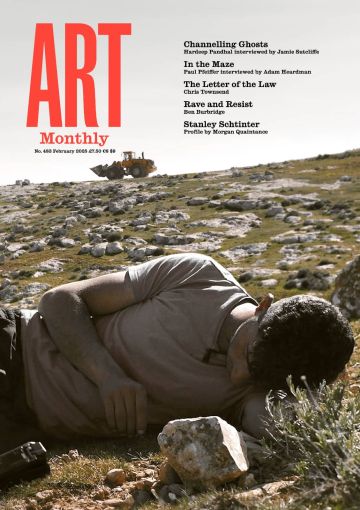

No Other Land, 2024, directed by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor

The previous edition of IDFA presented a tough challenge for its organisers. As the first major cultural event to take place after 7 October 2023 – it opened five weeks after Hamas’s attacks on Israel – the festival was seen as a litmus test. How would supposedly progressive cultural institutions respond to this geopolitical crisis? It was a tightrope IDFA inevitably failed to walk. The festival opened without official comment from organisers and when protesters, angry at this silence, unfurled pro-Palestine banners at the opening night, IDFA’s response was a rash statement that condemned the protesters’ wording but did not call for a ceasefire in Gaza. The Palestinian Film Institute accused the festival of silencing criticism of Israel, and around 18 filmmakers withdrew in protest.

Given this context, IDFA 2024 arrived under scrutiny. Between editions, director Orwa Nyrabia had been vocal in interviews about how the previous year had prompted internal reflection. That rhetoric is characteristic of cultural institutions facing public anger, but IDFA 2024 did wear that self-examination unusually visibly, even recruiting two artists critical of the institution, Ehsan Fardjadniya and Raul Balai, to conceptualise a marketing campaign addressing the controversy. That campaign, Dear IDFA, consisted of a trailer made from manipulated stock footage in which a couple picnic romantically in a field, oblivious to explosions taking place on the horizon. Meanwhile, a mournful voice-over describes an immigrant’s journey gone sour: ‘She gave me a passport to the promised Westland. Now I work as an inclusion brand, a cheap sell out, normal life, complicit, just complicit.’ An accompanying poster depicted a gingham blanket full of symbolism-laden goods – a watermelon, a bleeding dove, Dutch sausages, a coiled snake. It’s a curious campaign, but the allusion to the slipperiness of institutional claims of neutrality are hard to miss for anyone aware of the context.

Marketing, however, is packaging; IDFA’s substance lies primarily in the content of its programme, and the 2024 selection gave a tangible sense of a festival wrestling with its identity and moral obligations. The clearest theme to emerge across its many strands was a focus on censorship, which – given the previous year’s accusations – felt highly intentional. Explorations of freedom of expression recurred across the programme, from stories of Mexican journalists risking their lives to report on corruption in Santiago Maza Stern’s State of Silence, to Leila Amini’s intimate portrait of her sister’s attempts to become a singer in contemporary Iran in A Sister’s Tale, to Palestinian and Israeli filmmakers joining forces to chart West Bank land theft in No Other Land (collectively credited to Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor). This collaborative work made its Dutch premiere following a world premiere at Berlinale earlier in year, where it won Best Documentary but became a lighting rod for controversy when Israeli co-director Abraham was accused by some German politicians of anti-Semitism for describing Israel as an ‘apartheid-like state’ in his acceptance speech. The absurdity of that situation is made all the starker when considered in relationship to the film itself, a carefully unsensational but utterly devastating piece of on the ground journalism, which draws upon years of footage to offer insight into the life of a group of Palestinian villagers as they resist Israeli army bulldozers and violent settlers. At IDFA, No Other Land found itself at home alongside other films which, despite their different angles, ultimately wrestled with the same questions. How far can we be neutral observers? And what happens when those who document become part of the story? As Amini put it in a post-screening Q&A: ‘Do you shoot the house on fire, or do you stop to help?’

In Miguel Coyula’s Chronicles of the Absurd, it appeared to be the filmmakers trapped in the burning house. Ragged and propulsive, the film consists primarily of secretly recorded conversations between the director and his collaborator, actor Lynn Cruz, with enforcers of Cuba’s strict censorship laws, including police, government officials and fellow filmmakers. Each increasingly absurd interaction illustrated with mordant humour the complicity and doublethink that maintain censorship – and the ingenuity it takes for artists to navigate such systems.

Direct historical parallels with Coyula and Cruz’s experiences could be found in a retrospective of recent restorations by Afro-Cuban filmmaker Sara Gómez. Gómez’s films fascinatingly capture life in the early years of the country’s revolution, but her intersectional lens – she addressed topics such as inequalities faced by working-class women and the specificities of Creole culture – attracted government censor and, after her premature death in 1974, her films were neglected for decades. In recent years, thanks to the efforts of feminist scholars and the Vulnerable Media Lab, those films have been screened again, reminding us in the process of the need to constantly revise and revisit the cinematic canon.

More unexpected parallels were found in an inspired double bill that paired two mid-length works, Roisin Agnew’s The Ban and Mahmoud Atassi’s Eyes of Gaza. Agnew’s film is an arch, wittily edited archive doc exploring Margaret Thatcher’s 1980s anti-Sinn Féin ‘broadcasting ban’, while Atassi’s is a harrowing work of frontline journalism following Palestinian reporters in northern Gaza. Yet despite the films’ obvious differences this pairing proved illuminating, prompting powerful reflections on how attempts to silence can have spiralling unforeseen consequences. When, during the post-screening Q&A, Atassi repeatedly tried to phone the film’s protagonists, struggling against Gaza’s limited communications infrastructure, the exercise illustrated in real time how restrictions on the flow of information from the region shape the conversations we are able to have outside it.

Just as topical, but less engaging, was Piotr Winiewicz’s opening night film About a Hero. An attention-grabbing premise – Winiewicz’s script was generated by AI trained on the films of Werner Herzog, and its protagonist is a deepfake of the iconic filmmaker – meant anticipation was high. Yet despite strikingly surreal visuals, including one scene in which a bereaved widow is seduced by a toaster, the film’s blend of Herzogian parody with talking heads discussing AI’s impact was unconvincing. A (probably real) line from Stephen Fry, who also appears briefly as a deepfake, cut through the noise: ‘AI won’t beat us, but it will humiliate us.’ How much mediocre AI art will we watch before the gap between machine and human finally blurs beyond recognition?

More fun, and much shorter, was AI & Me, from artist duo mots. Screening in IDFA’s DocLab exhibition, this cheerfully vulgar participatory piece invited the viewer to sit before a camera and a screen which would, within seconds, gurgle out a bespoke, computer-generated assessment of their character, appearance and preferences. My half-garbled but worryingly plausible assessment – ‘late-20s woman … who has mastered the art of looking bored in cafes’ – was followed by a simulated topless selfie. My face then joined a churning gallery of fellow victims, manipulated into rotating variations of hairstyle, outfit and backdrop. AI & Me was just as creepy, funny and gimmicky as About A Hero but, at five minutes, much pithier. Ultimately, mots left us with the same unsettling message as Winiewicz: the technology that humiliates us today might well replace us tomorrow – who’s laughing now?

International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam 2024 ran 14–24 November.

Rachel Pronger is a writer and curator based in Berlin.

First published in Art Monthly 483: February 2025.