Michael O’Pray Writing Prize

In Defence of the Small Screen

Laura Bivolaru on viewing the moving image while moving

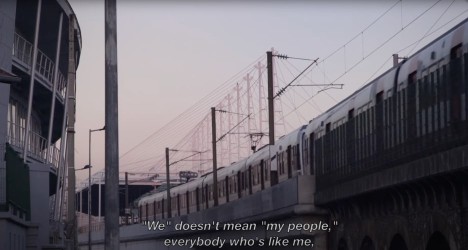

Alice Diop, We, 2021

Hopping on the London tube this summer from Turnpike Lane to Brixton, and in no mood to carry the extra weight of a book, I thought I would watch something on my phone. I picked Alice Diop’s We , 2021, which was streaming on Mubi at the time. I have watched countless films and television series on public transport before, something which has often made long journeys more bearable. But watching in transit has always felt that I was shorting the demands of the film, as if I was merely fulfilling the need to distract from commuting rather than genuinely engage with the film.

Travelling the last stop from Stockwell to Brixton, the images on my phone coincided with people waiting at a train station. As the tube pulled into its final stop and opened its doors, so did the train in the film, the extras barging in to take their seats. I found myself remaining in my seat, watching this unfold, even after the announcement advised us to check that we had all our belongings were with us when leaving the train. For a few seconds, my surroundings merged with the cinematic space in my hands and I sat confused, knowing that I was supposed to get off the train but feeling as though I had just got on the train. The small screen did not absorb me, as I was used to, but rather it allowed the two spaces to leak into each other.

It was perhaps a fated encounter. We follows the RER-B train line which crosses Paris along a north-south axis, stretching into its suburbs. The film begins with two grandparents and their grandson watching a stag in the Haute Vallée de Chevreuse National Park at sunset. We then follow numerous scenes that take place on the RER-B to Saint-Denis, Aubervilliers and Drancy, only to return to the same location at the end of the film, but instead of the bucolic scene of earlier, we arrive at a hunting party. Overall, the film comprises around 20 vignettes of largely ordinary people going about their lives, as well as footage from Diop’s family archive; the fragmentary structure offers glimpses at how different races, classes, ages, genders and occupations negotiate different types of societal togetherness. It is this lack of a linear narrative, however, that allowed me to return to the film the following week when travelling on the Overground to and from Peckham Rye without feeling irritated by a gap in time. If anything, I experienced a sense of continuity similar to when following an episodic television series.

The RER-B, like the London Overground, is a hybrid route with both above and underground stretches of track, and the train itself making a few appearances through the cityscape upon elevated structures. The difference is that I’m travelling through gentrified East London and flanked by towering glass blocks of flats and offices, while the RER-B traverses the Parisian suburbs and its banlieues – infamous council estates, home to the forgotten by those in power, and perhaps most famously and violently pictured in the 1995 film La Haine. Diop updates this image with tender, warm representations of daily life: people working, children playing and youth chilling out. The difficulties are still there, but they are counterbalanced by resilience and strength. In one vignette we see Ismael, a mechanic, call his mother on WhatsApp while fixing a car and bemoaning Paris’s cold weather, in other scenes people are mean to him because he is a foreigner. We also learn of his attempts to return home and the absurd bureaucracy of needing particular papers. Looking around me, I imagine fellow commuters having similar conversations with their families. I similarly start to remember a phone call I made in my first year living in the UK. Ismail sadly reveals he hasn’t been home to Mali since 2001. It is at this junction in the film that, despite the significant differences in our migration histories, the figure of Ismail takes on a vivid connection to my recent past.

By drawing from her own family’s history of immigrating to France from Senegal, Diop refuses the outsider position that is typically associated with image-makers in relation to their subject matter; instead she frames herself as part of the collective ‘we’ that the film represents. Born in Aulnay-sous-Bois, another area served by the RER-B – two stops after Drancy – Diop continues to put life in the banlieue at the centre of her filmmaking. On this occasion, however, she weaves it into the larger tapestry of the history of France. This is most clearly articulated when we see a commemoration of the execution of Louis XVI held at the Basilica of Saint Denis framed between the few minutes of footage Diop has of her mother and the video she took of her father before he passed away (which is also one of Diop’s first films).

In the footage of her father, we see him present his initial boat ticket from Mali to Marseille, recollecting his first years in France and how this move had an overall positive effect on his life. Diop mentions later in the film that her father had set up a burial fund which guaranteed their final return to Senegal. After adding to this fund on Diop’s behalf for years, her father advises her to begin contributing to it herself. Diop calmly replies that she wants to be buried wherever her children will be. During the softly narrated exchange we see images of untended nature populated with cranes, graffitied train carriages and concrete blocks, views which remind me of my childhood in the chaos of 1990s Romania.

It is a sunny day across all the three timelines I am currently experiencing – the film itself, my memories of childhood and the day I am watching this film in London – which again collapses the spaces into one another. I am pleasantly disoriented. But in the strong sunshine my reverie falters when I see a part of my face reflected on the screen of my phone, along with the numerous muddied traces of fingerprints. I have never considered where I would want to be buried before. Pondering this question led me to wish, for the first time since I started watching the film, that I was at home and not on public transport. I felt my own uprootedness had been somehow exposed and I found myself almost angry with Diop for breaking with the wishes of her parents. But behind these immediate feelings I also perceived the gap between first and second-generation immigrants, and how notions of leaving and belonging are experienced so disparately. I continue to find ‘belong’ a compelling term because it implies both possession and affiliation; is someone’s wish to belong in society also a wish to be ‘possessed’? How does the dominant group with its possession of contemporary political discourse exclude others from its image?

Towards the end of the film, Diop appears with the author Pierre Bergounioux in his library where he reads from his diary. Here she confesses that despite the differences in their lives, the stories he reads move her as if they were her own. His account of the poor, rural life of the region of Corrèze bears similarities to her storytelling based in the northern Parisian suburbs. Underlining both of their oeuvres, as Bergounioux remarks, is a ‘somewhat sacrilegious aim to drag from the darkness in which they were buried folk who have existed without ever finding any traces of themselves or their lives in the pages of books or in images that appear on screens’. In fact, We was directly inspired by Les Roissy Express: A Journey Through Paris Suburbs, 2000, a book of short stories about exchanges on the RER-B line by François Maspero and with photographs by Anaïk Frantz. In an interview, Diop recollects that she first read it 20 years ago and was so overwhelmed by the photograph of a black girl taken near the shopping mall of her childhood that she had to close the book. In order to be accepted by French society, Diop felt the need to camouflage her background, reflecting in the film on the way in which contemporary French society is emerging as a creole culture. It takes a certain degree of bravery to recognise what you have been conditioned to ignore, to represent those who have historically been refused screen time.

Watching the film on my little smartphone, the portraits of all the lives depicted were rendered even more intimately. It is a strange feeling to hold the image in your hands, not dissimilar to how a filmmaker holds and points a camera. As a spectator at the cinema or in a gallery, you are a disembodied pair of eyes, following whatever is being shown to you. On the phone, however, the power you have over the image becomes palpable – you can pause, stop, turn the volume up or down, add subtitles, or switch to something completely different. By gaining a sense of agency over watching, you become engaged with the responsibilities and questions of those who created the image.

To see We on various journeys around London allowed me to grasp Diop’s contemporary account of French identity in a different way than if I had encountered it on the big screen. Being on the move and outside the comfort of the home, surrounded by strangers, I felt the people of We closer, more physical, not simply characters in a film. In transit, personal histories are of lesser importance than the immediacy of negotiating your boundaries in relation with other commuters. The train is, for a limited time, a collective, porous body that gradually disperses as it reaches various desired locations. To make films from this open position of travelling is to portray life in cities as they slowly morph, it is also a dignifying process for people traditionally excluded from representation. With the small, portable screens in our pockets we might be able to access these films in ways that, for a few immersive moments, create one single space of communion.

Laura Bivolaru is a visual artist and writer based in London, and a winner of the Film and Video Umbrella and Art Monthly Michael O’Pray Prize 2022.

The Michael O’Pray Prize is a Film and Video Umbrella initiative in partnership with Art Monthly, supported by University of East London and Arts Council England.

2022 Selection Panel

- Terry Bailey, senior lecturer, programme leader, Creative and Professional Writing, University of East London

- Steven Bode, director, FVU

- Chris McCormack, associate editor, Art Monthly

- Tai Shani, artist

- Ellen Mara De Wachter, writer