Michael O’Pray Writing Prize

I Am a Photograph

Evelyn Wh-ell examines two French trans icons’ focus on image as surface

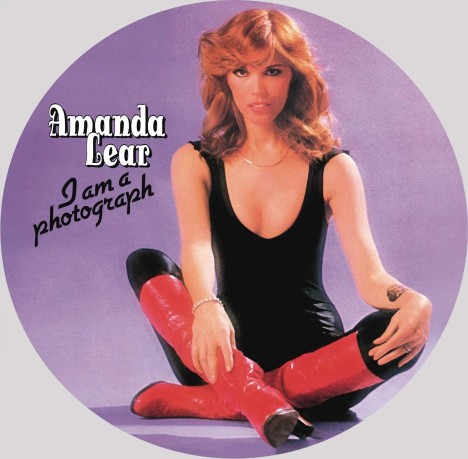

Amanda Lear’s 1977 album I Am a Photograph

The French former model Amanda Lear released her debut album, I Am a Photograph in 1977. On the titular track, Lear gave voice to her own image, singing not from her perspective as the flesh-and-blood pin-up star before the camera, but seemingly from the very medium itself. In the song, Lear repeatedly declares herself to be ‘a glossy photograph’, before listing all the particular properties born by an image reproduced among the pages of some unspecified magazine: ‘I am in colour and softly lit / overexposed and well blown up / carefully printed and neatly cut.’ The high-gloss surface of the photograph makes an appealing substitute for the dimensional figure it depicts – Lear’s body is replaced by her body-image, which performs on behalf of its subject. This substitute is, in Lear’s lyrics, ‘better than the real thing’, although the beneficiary of this improvement is initially unclear. The image appears significantly deprived; Lear’s ‘lips are parted’ but are ‘not for kissing’, while her ‘eyes are open’ but she is ‘not listening.’ For the viewer, then, the image might be a poor facsimile, but for Lear it seems this poverty might provide some respite. Without fleshy dimension, the depicted body is invulnerable, and Lear explains the superiority of the photographic image thus: ‘cause photographs do not complain / or cry, or love, or suffer.’

With I Am a Photograph, Lear articulates an ambivalence towards her own objecthood, and her complicity in this objectification. The photograph itself is impersonal, alienated and alienating, coldly perfect and unfeeling. Lear is laid before the viewer, made available for their pleasure without the capacity to protest. Yet, the detachment of alienation also entails a form of protection. This body, which is incapable of touching or being touched, can also not be prodded and pained. The desired and desirable body must be admired from a distance. It is with this ambivalence that Lear, while living in stealth mode, most closely articulates the specificities of a trans ambivalence towards becoming and being visible.

This ambivalence rehearses, on one level, the arguments developed by generations of feminist scholars for whom the image, especially the sexualised images that decorate the pages of the magazines to which Lear alludes, is a form of violence done unto the feminised body. Lear’s image in I Am a Photograph sings of a flattening akin to that which was perhaps most famously delineated by Laura Mulvey, for whom the cinematic apparatus worked to reduce Marilyn Monroe and other female starlets into shiny, sexy surfaces. However, by the same token, these surface images serve to enrobe the trans body, to protect via idealisation a body vulnerable to the real violence of being seen otherwise. In its role as substitute, the glossy surface of the photograph cloaks the very body it depicts – as Lear describes it, her parted lips are beyond the reach of a viewer’s unwelcome kiss.

The photograph serves as an instrument by which the trans body produces herself, a mode of self-fashioning whereby one can exist as one wishes to be seen without any chance that one can be disrobed. For unlike one’s clothing, one’s photographic appearance cannot be pulled aside to indulge in the transphobic trope of the ‘reveal’, a trope that lies behind films such as The Crying Game, and which forces the body back into a bio-essentialist framework that denies the very existence of trans bodies in their beauty. As Lear sings from her own self-image, she makes a claim for her mediatisation – trans being and trans bodies are inseparable from the histories of the media by which they may make their own appearance.

Three years prior to the release of Lear’s debut album, another French trans icon appeared immortalised before the camera. While starring in Maggie Moon, an adaptation of Arthur Miller’s play After the Fall for the Cinéma Olympic in Paris, the actress, singer, and activist Marie-France Garcia found herself the subject of a short film. This film, also titled Maggie Moon, was the work of Delphine Seyrig and Carole Roussopoulos, actress and filmmaker respectively, and members of the feminist video collective Les Insoumuses, or ‘Defiant Muses’. ‘Defiant Muses’ was also the name given to the recent exhibition dedicated to Delphine Seyrig and her creative collaborators that opened at Madrid’s Reina Sofia in autumn 2019, before moving to the Kunsthalle Wien in April 2022. This retrospective, its full title ‘Defiant Muses: Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s’, narrated Seyrig’s career as actress, videomaker and activist, while sketching her creative alliances forged in the liberation struggles of the late 20th century – including global feminisms, French anti-imperialism, anti-psychiatry, and gay rights activism. Through Seyrig’s participation in Les Insoumuses, the exhibition sought to recast the history of feminism as media history, demarcating a political movement whose aims, methods and organisations were marked by the instruments by which they critiqued contemporary conditions of political and visual representation.

Marie-France was a minor figure in this exhibition. She made an appearance in only the one film by Seyrig and Roussopoulos, and, even as Maggie Moon’s titular character, the closest thing to a protagonist the film has, Marie-France’s screen time is brief and fragmentary. In between footage shot in the backstage dressing room where Marie-France flirts with the camera whilst applying her make-up, viewers are provided with just two partial scenes of her performance as Maggie, a thinly veiled caricature of Miller’s second wife Marilyn Monroe, whom Marie-France had been impersonating since 1969 at the Alcazar in Paris’s Latin Quarter. Yet, in her familiar role, Marie-France dazzles. Rehearsing before an empty auditorium, host only to Seyrig and Roussopoulos, she delivers a rendition of ‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend’ as if to a full house, her diamante-dripping dress sparkling in the bright white spotlights.

Despite being employed as a stage actress, Marie-France knew how to perform for the intimate address of the silver screen. With Roussopoulos positioned in the wings, the camera captures Marie-France as she passes before the footlights and away from the lens, her body becoming blurred as she moves out of the camera’s set focal length. As she reaches the end of the stage, Marie-France turns to dance her way back towards the camera, her gaze locked down the lens to address the imagined future spectator captivated before her performance. Behind her head, the spotlights flare in a halo of white, catching lightly on every pale hair.

In her role on stage and screen, Marie-France inhabits an image. With her assumption of the guise of Maggie, already the disguised reproduction of another icon, Marilyn, Marie-France also assumes the qualities Lear attributes to the photographic image: she disappears into the surface, a version of the reflective crystalline face about which she sings, the promise of intimacy held at one remove from the viewer through layers of mediation. The flare of light that hides her face and the blurred focus which melts her outlines, are both interventions that foreground the cinematic image itself. These interventions are part of Marie-France’s own self-imaging and imagining. She is involved in the creation of herself as this vision, her insertion of herself into cinema as history and practice. Her movement across the stage, before the camera, displays her self-possession. Swaying her hips so that she can catch the light off her diamond-encrusted hem, she dances in and out of the shadows so that her face is thrown into dramatic relief. Marie-France imitates the figure of Monroe as the actress appeared on screen, as a celebrated image, Monroe alive and vibrant under the spotlight, not as the subject of sordid tabloid speculation or sentimental saccharine tragedy.

Even when Seyrig and Roussopoulos go backstage, Marie-France does not present the opportunity to see behind the scenes; she instead gives another performance, producing another image of herself, indeed multiple images, reflected between the large dressing room mirrors and the small handheld one she waves before her face whilst applying eyeliner. Marie-France refuses to concede to the trope of the ‘reveal’, refuses to allow the camera to flay her under a pretence of documentary immediacy. Seyrig and Roussopoulos are themselves also uninterested in questions of exposure. What concerns them is what concerns Marie-France and the other queer and genderqueer performers at the Cinéma Olympic: the low audience numbers which are threatening the show’s run. Seyrig, stepping before the camera, initiates this conversation with cast members who address both her and the audience of her film as they speak about their marginalisation in a minor venue in the impoverished 14th arrondissement.

In 1971, the Cinéma Olympic had been transformed under the direction of its new owner, Frédéric Mitterrand, then a young cinephile, later France’s first openly gay cabinet minister as minister of culture from 2009 to 2012. Mitterrand split the small venue into two smaller screens for the purpose of showing underground art films and 1940s melodramas, attracting amongst others Les Gazolines, an informal sisterhood of transsexuals, transvestites and drag queens, which included Marie-France. The cast of Maggie Moon had hoped to perform to a larger Parisian crowd than their own small circle of friends in a more prestigious venue. Even at the Olympic they were sidelined because the normal crowd of cinemagoers were not interested in a staged performance.

In Seyrig and Roussopoulos’s Maggie Moon, however, Marie-France found both her medium and her audience. In her performance for their camera, Marie-France’s embodiment of Monroe-as-image is translated into the visual language of the cinema screen behind her. Marie-France’s body, a flickering vision in black and white, becomes a cinematic image built out of the iconic images of the silver screen. Marie-France’s intervention in cinema is a specifically trans one, a trans claim to the cinematic image, a claim which causes transness to tenderly contaminate all those caught in its light.

In 1975, Seyrig wrote about Marie-France’s performance in a letter to her son, Duncan Youngerman. Seyrig was enthused, describing how Marie-France’s ‘understanding of Marylin is more than just imitation – real insight – really moving’. More than just imitation, Marie-France provided a lesson in identity transformation through the cinematic image, as Seyrig went on: ‘I feel very much myself like a transvestite […] I am attracted to the feminine image and have learned to construct it, as they are and have.’ For Seyrig, this theory of transformation was generalisable to all performers, whose chosen profession originated in ‘this great desire to change identity, to not be restrained to the one identity society has trapped us into’. But it was Marie-France, in all her trans specificity, her understanding of the filmic medium, which allowed Seyrig to come to such conclusions.

In her layered citation of cinema, her embodied theory of the image as site of transformation and protective ideal, Marie-France placed her transness at the heart of the medium and its history. Her inhabitation of an image of an actress inhabiting an image of femininity (Monroe) before another actress attempting in her own work to inhabit the same image (Seyrig) extends far beyond a simple trans-inclusive feminist reading, wherein ‘trans’ serves as mere addendum. Instead, Marie-France’s presence revises ‘Defiant Muses’s own exhibition thesis, claiming feminism itself as historically trans, and media history as properly transfeminist. Alongside Lear, Marie-France produced an understanding of the image as a place of trans realisation which has the potential to similarly realise something in its viewer. To read Seyrig’s ‘feeling like a transvestite’ perversely but literally, the cinematic image is a vector to convey transness to its spectators – a vector in which one recognises one’s desire for an ideal which is, in Lear’s words, better than the real thing.

Evelyn Wh-ell is a writer, artist and researcher, and a winner of the Film and Video Umbrella and Art Monthly Michael O’Pray Prize 2022.

The Michael O’Pray Prize is a Film and Video Umbrella initiative in partnership with Art Monthly, supported by University of East London and Arts Council England.

2022 Selection Panel

- Terry Bailey, senior lecturer, programme leader, Creative and Professional Writing, University of East London

- Steven Bode, director, FVU

- Chris McCormack, associate editor, Art Monthly

- Tai Shani, artist

- Ellen Mara De Wachter, writer