Film

Andrea Luka Zimmerman and Adrian Jackson: Here For Life

Hettie Judah reviews a collaborative film that follows the lives of Londoners as their city changes around them

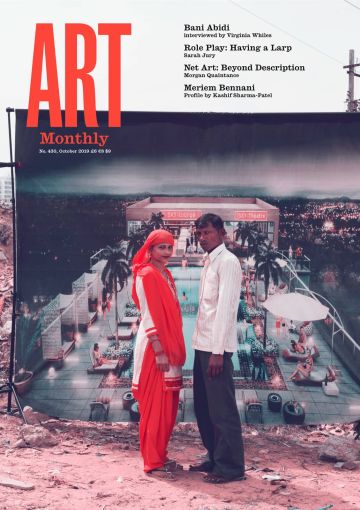

Andrea Luka Zimmerman and Adrian Jackson, Here For Life, 2019

‘Here For Life’ runs the jaunty slogan on hoardings outside a luxury hotel development. Whose life, though? From the pavement two men survey the building site, Londoners both, and dented around the edges. Patrick is of East End gangster stock and still sports a sparkle and sharp trim, though the hair is almost white with age. Richard is tall, voice deep as a lift shaft, with one blind, milky eye beneath bunched Rastafarian locks.

Patrick had known the building as a courthouse, and recalls his times in the holding cells as if fondly. ‘Could you smoke in there?’ asks Richard. ‘In the cells? Yeah, ’course you could.’ Walking the streets of London’s east together, past new investment properties, signs restricting access, and freshly strung barbed wire, Patrick bemoans the privatisation of his manor: ‘I felt like it’s mine, and then they’re taking that away. Bastards.’ ‘I never felt like I owned something’, says Richard quietly. ‘I’ve always been looking for somewhere to belong.’

Who owns the city? To the ten performers participating in Andrea Luka Zimmerman and Adrian Jackson’s Here For Life – a film and collaborative process produced by Artangel – this question underpins a daily struggle for stability, love and basic rights. Zimmerman throws us straight into their intimate company, dealing only shards of biography along the way. None has been afforded a frictionless route through life. There has been abuse, addiction, juvenile detention, crippling struggles with mental health, murdered parents, systemic racism, sick children, chances missed, opportunities never offered, lives in which the only imperative is survival. Who owns the city? In the London of investment properties and privatised ‘public’ spaces, not these people, not any more.

Twenty years ago, Artangel invited the Brazilian politician and theatre director Augusto Boal to host three sessions of legislative theatre in the Debating Chamber of the Greater London Council – a democratic space for the city that had been shut down under Margaret Thatcher. Boal pioneered a participatory performance method known as Theatre of the Oppressed. It was not, as he used to say, political theatre, but theatre as politics.

In Theatre of the Oppressed there are no spectators, only participants. Performance is a format through which changes can be tested and protocols agreed: if you don’t like the way something is happening on stage, you step in and play the scene differently yourself. Back in the GLC building in 1998, Adrian Jackson directed the session on transport; he has since used Boal’s methods in working with the homeless theatre group Cardboard Citizens. In Theatre of the Oppressed, imagination is a tool for democracy: a little fiction helps communities reach a deeper truth. The principle of participation means that in this debate it is not always those dogs that bark loudest who win.

Such elements of fiction and fantasy infuse Here For Life. Zimmerman locates a calculatedly theatrical segment of the film in the chiaroscuro of a derelict interior: a staged punch to the face, a dinner party of snobs, tableaux vivants. The rest of the film presents as if a slice of sun-soaked verité, spiralling around the Nomadic Community Garden off Brick Lane in the dry heat of June 2018. A brindle bullterrier digs doggedly in a plastic water tub. Butterflies bounce through lolling flower heads and trains trundle past. Occasionally we follow one of the performers home, or catch part of their story: ‘I have a really dysfunctional pattern with men, and after I ended up in the hospital a second time ... ’ But their tales enter the common wealth as part of the collaborative process of creating the film and a play they stage within it. Threads of the participants’ stories are picked up and told by different voices. There is no space for self pity here, though there is space to cry. Who owns the story? In this piece of fiction as truth, no single individual.

Zimmerman fluidly integrates theatrical performance and process into a beautiful piece of filmmaking that never romanticises its subjects. She and Jackson bring voices to the screen that are rarely heard, and present fragments of lives that are overlooked in the cultural mainstream and little considered in the evolution of the ever-accelerating, ever-modernising city. This is not mere representation: the cast of Here For Life present themselves as creative forces: they sing, they cook together, they perform poetry, they care for one another. Zimmerman and Jackson’s fantastical and at times stagey methodology accesses something deep and complex, suggesting the potential of collaborative acts of creation as part of an unfolding process.

Hettie Judah is a writer based in London. Her book Art London: A Guide to Places, Events and Artists is published by ACC Art Books.

First published in Art Monthly 430: October 2019.