Feature

Group Practice

Paul O’Neill on the collective alternative to the romantic cliché of the lone artist, curator and critic

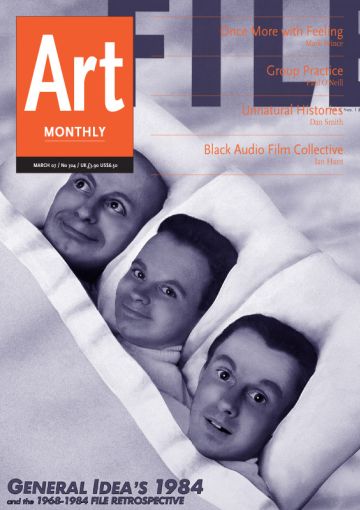

‘SHUT THE FUCK UP!’ shouts General Idea in its video mock documentary of the same name from 1985. Looking directly into the camera, three young artists AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal continue their rant: ‘I am not going to be a media whore, I won’t play bad guy to your good guy, boho to your bourgeoisie, we are supposed to be romantic, untamed, while our artworks are slipped back into the marketplace, blue chip investments for level headed fetishists ... I’d like to paint them into a corner, I am not going to shit on a canvas and they’ll call it art, it doesn’t matter what they are saying as long as they are talking ... no matter what they will dress you up ... do you get the picture, do you know what to say, SHUT THE FUCK UP!’

General Idea’s high camp critique of the art world, the mass media and its clichéd image of the unique artist is a still timely reminder of the ever-increasing power of the contemporary art market, but it also serves as an indicator of how little has changed since in relation to the historical institution of the individual producer – the artist, the curator or the critic. In its attempts to undermine the role of mediation within the art world, General Idea highlighted the art world’s capacity, seemingly unaffected by such critiques, to maintain its investment in a falsified image of the creative individual. Recent labels such as ‘biennial art’, ‘museum art’ or ‘art fair art’ have also demonstrated how any art shown in a given context can be absorbed, sometimes intentionally, by the very conditions of their display – with the word ‘art’ regularly exploited by event organisers as a generic stand-in term for everything that is displayed under these circumstances. Concession is now made for interdisciplinary discussions, conferences and artist projects as integral parts of mega exhibitions and art fairs alike which accommodate the participation of less materialised and more discursive modes of group practice.

When Hans Ulrich Obrist remarked that ‘collaboration is the answer but what was the question?’ he was probably alluding to the necessary function of such questions as a means of sustaining his eternal interviews project; but equally he may have been thinking how collaborative practice is often reduced to the individual statement. Widespread interest in collaboration has led to an increase in the number of self-organised initiatives over the last few years, accompanied by a large number of survey exhibitions, publications and projects that have brought these group agencies together under a single rubric. In this context does any collective art project or group-work still have the potential to be subsumed in the same way as a self-contained artwork by a single author? When General Idea declared that working in a group had freed it from ‘the tyranny of the individual genius’, or when Art & Language described its output as having ‘no grand oeuvre, unified by romantic personality’, or Group Material made a plea for an understanding of ‘creativity unrestricted by the marketplace or by categories of specialization’, they were all expressing a common desire for an alternative to the autonomy of the artist, the curator and the critic. This leads to the question of whether a merging of people and practices can continue to offer any sustainable resistance to the cult of creative individualism, and whether the ‘collective’ might be just another marketable brand in disguise.

When I interviewed Bronson in 2005, he said that General Idea was modelled on the idea of a rock band. ‘We thought of ourselves in really pragmatic terms as a group. I think if any of us had played instruments we would have formed a proper rock band. So we didn’t think of ourselves as a collective.’ Bronson suggested that there was a much needed distinction to be made between the liberating potentiality of a ‘group’, formed out of mutual friendship, and the restrictive structure of a ‘collective’, limited by certain ideological or organisational principles.

Underlining Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics was his portrait of a general shift towards group work, polyphonic exchanges and multiple practices that had gathered momentum from the late 60s onwards. Although Bourriaud dedicated a whole chapter to the legacy of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and the influence of his distributional tactics on art of the 90s, his failure to highlight Gonzalez-Torres’ involvement with Group Material was a serious oversight in this respect. Equally, the now familiar yet equally reductive Anglo-American critique of Bourriaud’s analysis has also tended to ignore the momentum of this move towards collaboration, instead pitching individual artists against one another.

As a mutating collection of members active between 1979 and 1996, Group Material employed the process of exhibition-making as a space for potential political and social formation, with the exhibition form functioning as a shared site of participation among individuals, and the event of the exhibition enabling a further place for discussion and a social public forum. Exhibitions such as ‘The People’s Choice’, 1981, subverted the manner in which the display of art had become standardised and how such formations were established. By interrupting the traditional museum/collection model, ‘The People’s Choice’ presented material that was determined by non-professionalised cultural experts: locals were invited to contribute things from their homes to the exhibition on East 13th St, New York. ‘Americana’, shown in the context of their first institutional show at the 1986 Whitney Biennial, presented a salon des refusés of marginalised artists with socio-political concerns. Their work, set alongside products from supermarkets and department stores, broke the boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture by questioning the function of cultural representation and hierarchies of cultural production, while ‘Democracy’ at Dia between 1987 and 1989 was organised as a cycle of discussion-led events and collaborative shows divided into four sections: Education and Democracy; Politics and Election; Cultural Participation and Aids; and Democracy: A Case Study. As one of the many founding members of Group Material, Julie Ault has most evidently continued its legacy by questioning the multiple roles of artist, designer, curator, writer, historian and editor in her numerous exhibitions and publishing projects, which have continually sought to reconfigure the past in the present. These have included essential publications such as Alternative Art New York 1965-1985, 2002, and Come Alive: The Spirited Art of Sister Corita, 2006. In addition to which there is her ongoing artist-collaborations with Martin Beck, the latest of which, ‘Installation’, 2006, at Vienna Secession, utilised Gonzalez-Torres’ series of photographs ‘Untitled’ (Natural History), 1990. The titles from this – Patriot, Historian, Humanitarian, Author, Conservationist etc – were deployed as a way of reading or classifying the exhibition material that coincided with the publication of the Gonzalez-Torres catalogue raisonné edited by Ault. All of these projects examined the complexities of classification, conventional display and the difficulty of transcribing any fixed notion of alternative history with a consistently collaborative approach to exhibition-making.

The significance of both Group Material and General Idea as precedents for a current trend towards group work was highlighted when they were selected as part of ‘Collective Creativity’ at Kunsthalle Friedericianum in Kassel in 2005. This exhibition and its supporting publication posited the view that all creative work was already collaborative, at least in principle if not in name, while evidently articulating group work as some form of resistance to the dominant, market-driven model of production already supported by our existing sociocultural institutions. The curators of the show, Zagreb-based curator collective WHW/What, How & for Whom, called for greater visibility of group practice over the years, with all collective work put forward as the results of alternative forms of sociability – even if their objectives fail to have any lasting effect beyond the social subsystem that is the art world. ‘Collective Creativity’ documented historical avant-garde models such as Dada, Surrealism, and Fluxus alongside an eclectic mix of recent and contemporary group activities from Europe, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the US. As such, the project reflected on a wide variety of heterogeneous approaches to multiple authorship across social, cultural and historical divides. WHW presented the project as an act of kinship, a show of solidarity with the general spirit of the collectivism shared by many of the assembled exhibitors, for whom joint work provides a potentially utopian space for co-productive discourses.

‘Collective Creativity’ was an important survey. In their introductory essay for the catalogue, WHW declared that ‘collective creativity’ means ‘collective power’ that calls upon communistic forms of work and production for the good of the whole, where ‘individual energies are bundled together in these collective works and common interests prevail or a shared result is achieved’. Herein lies one of its problems. The packaging of all these groups as a common ‘collective’ translates into a flattening-out of each specific group formation. Group Material becomes interchangeable with General Idea with Gilbert & George with IRWIN and so on. It was hard to avoid perceiving ‘collective creativity’ as representing a far too benevolent, and perhaps idealistic, view of group models of practice as a united collectivity. Surely what is common to each group is that they prefer to work with each other rather than with others. Why the need to quantify a collective connectivity?

The rallying cry for collaboration as a strategy for countercultural organisation has been a recurrent theme in recent exhibitions and publications. Among the most recent of these is: ‘Be Marginal, Be A Hero’, which began in January 2007 with Danger Museum, the first of five collectives to curate projects at Wysing Arts Cambridge over the coming months. Earlier examples include the exhibition and accompanying ‘user’s guide’, ‘The Interventionists: Art in the Social Space’ at MASS MoCA that ran from May 2004, and ‘Get Rid of Yourself’ at Halle 14 and the ACC Gallery in Leipzig, Germany in July 2003, which attempted to map out common, autonomous approaches to societal relationships through gatherings of collective initiatives. Make Everything New: A project on Communism, 2006, edited by Grant Watson, Gerrie van Noord and Gavin Everall, is a Book Works publication which seeks ‘to rescue communism from its own dispute’ through collective imaginations, and Self-Organisation/Counter-Economic Strategies, 2006, which brought a range of texts and documented projects together as a toolbox for self-organised activities initiated by Superflex. With all this togetherness going on, it might be worth considering whether self-organisation can be seen as a disguise for just another model of self-enterprise, functioning as a self-help conduit to the market, rather than as an alternative model productive of social processes of communication and commonality based on shared exchange. Even a brief glance at these projects will reveal how ubiquitous certain collective and self-organised models have become right across the board.

After four decades of institutional critique, the prevailing image of the artist is still one that adheres to a vanguard position for the artist as autonomous subject – an individual author and/or producer of the unique work of art within the context of the institutions of art and beyond – with artistic and/or curatorial autonomy sustained throughout. In discussing institutional critique, it is hard to come up with a list beyond the established canon made up of the usual individual suspects, whether it begins with Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren or Hans Haacke or ends with Mark Dion, Andrea Fraser or Renée Green. Might we consider General Idea or Group Material as part of a parallel history of institutional critique of individual creativity? Equally, if we consider how much curatorial practice has been collaborative over the last decade, we still have more of an understanding of who certain curators are than what they actually do, which may also be the result of celebrity culture and the popularisation of art as part of the global entertainment industry. This is in spite of what I would call ‘the Obrist paradox’ whereby the most visible curator of the last decade, Hans Ulrich Obrist, has curated almost all of his projects in collaboration with others. So it is worth asking whether we are finally beginning to see a noticeable paradigm shift in recognition for the collective as a now dominant, and no longer merely emergent, paradigm of the moment. Is all this interest in the ‘collective’ merely a fleeting attraction or a more genuine falling out with the cult of the individual producer? Are we witnessing brief love affairs or committed partnerships?

Returning to General Idea, it may be possible to shed some light on the matter. Felix, June 5, 1994, 1995/1999, was its final collaborative work. It is a large public billboard depicting a scaled-up image of Felix Partz laid out in his bed – eyes wide open, unable to shut, his skeletal face looks down from a height up above. Surrounded by his most beloved possessions, he is wrapped in multicoloured bed-clothes, his head resting upon a bright yellow pillow. His favourite shirt is buttoned right up, covering his body, emaciated by the illnesses that have brought about his demise. It is a beautiful, yet unsentimental picture of death. An image of a lost friend, taken by AA Bronson, it reminds us that the foundation of any group creativity is the common bond of friendship. Felix, June 5, 1994, acts as an emotive signifier for all group work. It tells us that all groups are made up of individuals who happen to believe in art, who like working together and who sometimes even love each other. Maybe, unintentionally, or perhaps unwittingly, it also shows us how much some of us would rather not go it alone.

WHW/What, How & For Whom collective is included in ‘Société anonyme’, Frac Île-de-France, Paris March 15 to May 13 2007. AA Bronson is among the guest curators of this year’s Oberhausen Short Film Festival, May 3 to May 8 2007.

Paul O’Neill is an artist and curator. His edited anthology Curating Subjects is published by de Appel and Open Editions.

First published in Art Monthly 304: March 2007.