Profile

Frida Orupabo

Phoebe Cripps on the Norwegian artist’s use of historical archives to return an unsettling colonial gaze

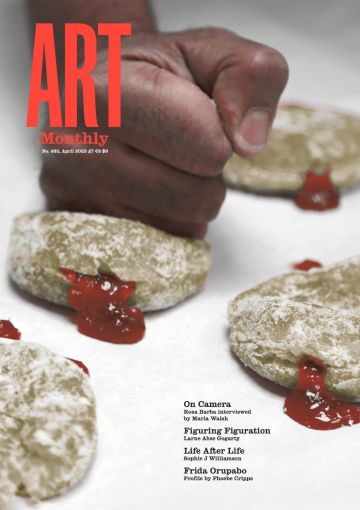

Frida Orupabo, ‘I have seen a million pictures of my face and still I have no idea’, installation view, 2022, Fotomuseum Winterthur

The Oslo-based artist and sociologist uses photographic collages, featuring faces drawn from historical archives, horror films and other sources, to address the colonial gaze and the everyday experience of simultaneously seeing and not being seen.

The title of Frida Orupabo’s solo show at the Fotomuseum Winterthur last year was ‘I have seen a million pictures of my face and still I have no idea’. She has seen a million faces, mining them, sorting them, dismembering and distorting them into new subjects. A face is where we meet the world, our primary site of uniqueness. Through her chosen title, a quote from Elaine Kahn’s 2015 poem ‘I Know I Am Not an Easy Woman’, Orupabo professes that she is all these faces – culled from horror movies and YouTube, colonial archives and Instagram – that haunt her collages.

For Orupabo, the question always begins with that of belonging; she sees her work as solutions to problems, one of them being that images such as hers do not exist and therefore need to be created. Yet her photographic collages, usually just smaller than life-size, mounted on aluminium as objects and held together with split-pins, ask more questions than they provide answers. Her images of black bodies prod and pluck at the flat notion of representation so frequently invoked as being about telling stories – instead, Orupabo offers us counternarratives.

In an interview with the Norwegian newspaper DN in 2018, Orupabo said, ‘In the beginning, I wanted nothing but a kind of diary. A dialogue with myself. A place for my frustration, in terms of ethnicity, complexion, sexuality, gender. I work with pictures I can recognise myself in. They rarely saw me when I grew up.’ That last line – ‘They rarely saw me’ – underlines an invisibility in Orupabo’s experience of growing up with a Nigerian father and Norwegian mother in a small town near the Norwegian coast. But it also belies the opposite, a hypervisibility of difference in which ‘They’, an indeterminate mass that could also include Orupabo herself, was incapable of seeing a person beyond the category of ‘other’. In the press release for an exhibition last spring at New York’s Nicola Vassell gallery, Orupabo cited the Portuguese artist and writer Grada Kilomba: ‘After one is de-idealised, one becomes idealised, and behind this idealisation lies the danger of a second alienation. In both processes one remains a response to a colonial order.’

The politics of vision reverberate in Orupabo’s new research that looks at vintage horror films such as Halloween, 1978, The Pit, 1981, and Timité Bassori’s superlative La femme au couteau, 1969. Orupabo is particularly interested in how the gaze is employed to elicit fear. The famous opening sequence of Halloween uses a four-minute tracking shot that folds the dimension between murderer and audience so that we are clutching the knife and wearing the clown mask. When the mask is put on, the field of vision narrows to its eyeholes. Orupabo recalls a comedy show she watched on Norwegian television as a child, Brødrene Dal, in which an old woman cuts the eyes out of a painting in order to spy through it. The impression of eyes moving behind the portrait’s stillness has stayed with her as a shorthand for the horror of seeing and (not) being seen.

On Orupabo’s Instagram account (initially a creative outlet alongside her job as a sociologist and social worker until it was notoriously ‘discovered’ by the artist Arthur Jafa in 2014) is a recent post of former basketball star turned right-wing provocateur Dennis Rodman. Dressed as a bride, with blonde wig and brown lip gloss, he says, ‘I’m all of both worlds here’. Orupabo’s subtitled GIF, taken from Tumblr which, in turn, was taken from Rodman’s promotion for his first autobiography, Bad As I Wanna Be, reintroduces 2006 Rodman to her followers. Presented without context, the post foregrounds the potential transcendence of the quote and not Rodman’s more recent transgressions (sidling up to Donald Trump or Kim Jong-un, and awaiting numerous assault lawsuits). Orupabo pairs the GIF with her own screenshot, in black and white, as though it is a scan of a century-old photograph with a scratch across Rodman’s pixelated face. The image is starker and more harrowing in monochrome, conjuring Rodman speaking from beyond a void – of gender and racial discourse, of pop culture moving on from him – as if from beyond death.

More than any other form of visual art, photography is inseparable from the eye; the camera is frequently invoked across art history and theory as the eye-turned-machine. Smartphones and Instagram have made cyborgs of us, both unwittingly distant from and irrevocably complicit in our imaging of ourselves and others. Assembling together fragments from films, internet screenshots, colonial archives, eBay listings and old erotic photographs, Orupabo’s collages (which she began making after Jafa suggested she print some of her Instagram pieces) destabilise the creator and viewer in ways that parallel Halloween’s tracking shot. Who are these reconstituted bodies, these new subjects for?

Orupabo calls these figures her ‘subjects’ – a historically loaded term for both the photographer and the photographed. Most of the body parts are taken from colonial archives, often those of missionary photographers sent to document the conditions in schools and congregations. A 1985 article about the Basel Mission Archive, whose images Orupabo has used, states that, ‘above all, pictures were taken to appear in the literature issued to supporters at home’ – so the lives of those colonised for profit were now being captured for donations from back home in order to supposedly ‘civilise’ the subjects. In Orupabo’s reworkings, the faces of these people frequently stare directly at the viewer, soliciting an interaction, a response – anything adequate enough to meet their gaze. Sometimes she works in an animal or animal parts: a swan, a crow, a bat’s wing, a dancing snake that mirrors the coiled bend of a woman. She is always willing us not to look away, yet to look too closely feels abject and voyeuristic. In previous sculptural installations, such as for 2021’s Future Generation Prize, Orupabo has put the viewer in her role – the audience as the butcher, as Frankenstein – presenting individual collage pieces as moveable. Her almost universal use of black and white enables these uncomfortable conjoins to appear perversely whole at times. In the new work Leading the Blind, a trio of stone figurines of slaves, chained and naked, are being led by a blindfolded creature, also carved in stone. The overly simplistic bodies of the slaves have had each of their heads replaced by a photograph of the same young girl, repeated but flipped and cut differently each time by the artist. She, or they, stare at us intensely and directly. The photographic detail of the face so clearly does not fit the time of the bodies, yet the two merge absurdly, almost in proportion. Orupabo is asking questions about contemporaneity, in which history, immovable and compressible as stone, looks squarely back at us.

Whereas Jafa’s work veers towards the pessimistic, echoing the stuttering pervasion of images of death and violence against black bodies on the internet, Orupabo’s work appears, perhaps tentatively so, to offer a way out. Her images both re-perform and subvert this violence and horror in order to hold rage close and see what can come of it. Of a new collage, Sandwoman, she says ‘it’s hard to tell if this woman will put you to bed or wake you up’. Sandwoman’s contorted body is muscular and deformed, yet gleaming, glittering. One of her rare subjects to turn away from the viewer, she appears to lead the way, away from looking and towards new dreams and possibilities that might be impossible to categorise.

Phoebe Cripps is a writer, editor and critic based in London.

Frida Orupabo is shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize at the Photographers’ Gallery, London to 11 June 2023, and her exhibition ‘Things I saw at night’ continues at Modern Art, London to 20 May 2023.

First published in Art Monthly 465: April 2023.