Books

FILE

Sally O’Reilly flicks through every issue of General Idea’s FILE magazine from 1972 to 1989

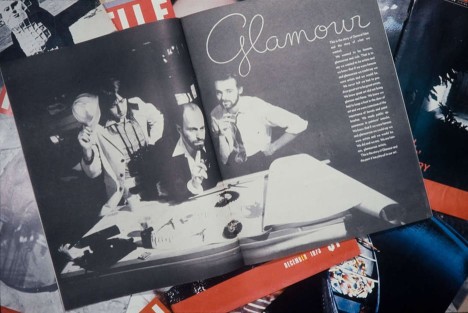

General Idea publicity shot for FILE Megazine

Is it inevitable that every venture that persists over time, no matter how counter-cultural its initial aspirations, becomes slickly professionalised and indistinguishable from its original nemesis? We’ve witnessed this trajectory innumerable times, where angry young artists or musicians, if they don’t drop into oblivion of one sort or the other first, eventually take their place among the venerable stalwarts of the circuit. Art self-publishing, however, has a couple of inbuilt safety mechanisms that guard against this model of creeping conservatism. The first is the high cost of print production that wears the producer down before long; the second is the limited readership for such niche publishing. Art has never been a top seller on the newsstands: you’d be horrified to know the comparative circulation of, say, Art Monthly and Cage and Aviary Birds Weekly (the clue is in their respective frequency). As the shifting topography at the self-publishing fair Publish and Be Damned demonstrates, the scene is volatile and capricious, with a title’s survival depending mainly on the pure grit of the people that produce it.

An appreciation of this rather inclement terrain makes the persistence of FILE quite remarkable. The magazine was published by AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal of General Idea between 1972 and 1989 and ran to 26 issues in all. Thumbing through the recently republished box set – with every issue reproduced as a facsimile, the pages surrounded by a broad white border as if they were pinned on a gallery wall for individual inspection – offers a fascinating glimpse of history as a process in motion. In earlier issues the mail-art aesthetic prevails, with cutout-and-stick-down heterogeneity producing a maelstrom of information that is often difficult to penetrate. Later on the livery, content and pacing of the publication changes dramatically until, in the final two issues, its clarity and professionalism is like cut glass compared with the papier-mâché of its origin.

FILE started out as a reflection of the sensibilities of a small group of artists practising in Canada. It was a networking tool for a community before so ghastly a word was ever applied to the ingenuous act of communication with intent. It includes a directory of artists, an image request bank – where individuals can post calls for ‘images of grease’ or ‘an altered postcard of your town, photographs of anything left on the moon’ – and letters from elsewhere written by group members on sightings of acquaintances as well as celebrity artists. The parade of people include some we recognise, such as the ever-looming Andy Warhol and the postmaster of mail art, Ray Johnson, as well as those who never quite entered the annals, their names repeating like that of an absent friend, and figures like Vincent Trasov’s Mr Peanut, who has receded to a status of oddity, occasionally haunting the pages of history books, although no one really knows what he actually did.

Although the feeling of being on the wrong side of the insider’s encampment when reading these ‘news’ columns and profile features is unavoidable, the standard of writing and the use of the magazine as a site of production is beguiling and its content often hilarious. AA Bronson’s account of haircuts at an opening of Colin Campbell’s videos, for instance, reads like a Donald Barthelme short story, while elsewhere the editors ask the readership to take part in a survey of a pseudo-psychogeographic nature: the border between Canada and the US is to be drawn on an outline of North America, where the two countries are indistinguishable as a single landmass, and in the following issue the results are published. One subscriber simply scored the continent in half across a diagonal, while another drew a border that allotted Canada a thin strip around the entire coastline and the US the lion’s share of land, reflecting its ‘vast inner power’.

Such playful politics abound in FILE. The phenomenon of Miss General Idea, for example, becomes an allegory through which to re-evaluate the art world, as the artists explain in an interview in the Journal of Contemporary Art in 1991:

‘There are five elements to [the] structure: “General Idea” as representing the “artist;” “The Miss General Idea Pageant,” which we think of as the process of creation; “Miss General Idea” as the artwork itself; “The Miss General Idea Pavilion,” which is clearly the museum or the gallery; and what we call “Frame of Reference,” which is essentially the audience and the mass media, as in File magazine. So we can assemble all our work within that structure and recreate the art world, and the world of media that surrounds it, within the structure of our own work.’

Throughout their collaborative practice, until the death of Partz and Zontal in 1994, the artists often constructed a pastiche of ‘real-world’ entity as a vehicle of stealthy critique. Their logo for the German AIDS foundation aped Robert Indiana’s LOVE logo, which they described as ‘transforming and transvaluing that relatively familiar image’. This gives a clue to FILE’s eventual form, which, to all intents and purposes, looks like the slick publications it once punkily undercut. The project was initially intended as a parasitic art project that occupied the territories staked out by the mainstream in order to pass into a general distribution system by dint of its apparent visual familiarity, thereby exposing the unsuspecting to content that bucked the various commercial, heterosexual, hierarchical and institutional norms. In 1977 Time/Life publishing brought a lawsuit against FILE for its use of capital letters on a red rectangle (as William Burroughs put it in an editorial quote, ‘pay back the red you stole’), which can be thought of as the ultimate achievement of their goal: the big fishes’ recognition of the collective power of undercurrents. The editorial clarity of the final issues of FILE – with their substantial page-based projects by Haim Steinbach and Barbara Kruger and transcripts of a panel discussion on Baudrillard – can be read as evidence of buckling under the weight of a wider readership’s expectation. As the editors’ column in the final issue states: ‘In this era of corporate culture, the culture is corporate: FILE cannot continue without becoming enmeshed in the deadlines, managing editors, international correspondents, advertising representatives and other signifiers of the mundane world.’ Another more gratifying explanation, however, might be that to continue to burrow beneath the flesh of the host, the parasite necessarily adopted more and more convincing disguises.

FILE Megazine General Idea, ed Beatrix Ruf, jrp ringier, 2008, 2024pp, hb, £125.00, 978 3 9058292 1 1.

Sally O’Reilly is a writer and a dean of Brown Mountain College of the Performing Arts.

First published in Art Monthly 329: September 2009.