Feature

Expresso Punko

Following the orgy of 1960s nostalgia, Andrew Wilson reviews the inevitable revival of interest in 1970s Punk signalled by a clutch of new books on the subject

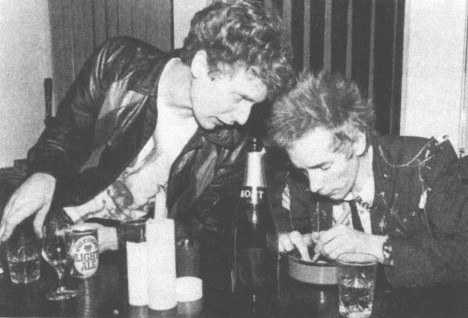

Malcolm McLaren and John Lydon at EMI, October 1976

The history of pop music in post-War Britain effectively began with the discovery of Tommy Hicks, singing in the basement club of the Two ‘I’s coffee-bar in Old Compton Street, his subsequent signing by the two impressarios, Larry Parnes and John Kennedy, his transformation into Tommy Steele and the release of his first record in 1956, Rock with the Cavemen. Though now a very prosaic train of events, at the time it was revolutionary because Parnes and Kennedy tapped directly into the coffee-bar youth culture of the period and re-invented and defined that culture through an object of consumption. In this their inspired use of the popular press was crucial; once they had succeeded in getting Tommy into the papers ‘they were away; his myth was self-nourishing; it grew from feedback’, explains George Melly; ‘by describing Steele’s effect on his early fans with a kind of salacious prurience, the papers ensured that the behaviour they deplored appeared increasingly attractive to an ever-widening adolescent public’.

Twenty years later, at 430 Kings Road, such an approach was being employed by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood with the creation of the Sex Pistols as an advertisement for their shop ‘Sex’. Within the frame of reference of his Situationist inheritance, McLaren was not just creating another pop group but like his hero Parnes, whom he came to imitate in a disturbingly foppish manner, he aimed to transform the existing youth-culture through a manipulated reorganisation of the ‘tribes’.

Where, in the 1950s, we had been delivered the likes of Billy Fury, Marty Wilde, Rory Storm and Johnnie Eager, names that offered a sublimation of sexual possibilities, McLaren, who once admitted that Johnny Kidd was more of an influence on his generation than Bob Dylan, promised a Dickensian underclass of the dispossessed, the outlawed and the socially ostracised embodying a reactive barbarism that could operate under the rubric of ‘Modernity Killed Every Night’: names like Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious stood for the no / future.

The stations that McLaren and Vivienne Westwood passed on their route to the launch of the Sex Pistols and the supposed creation of Punk are clearly visible. McLaren’s obsession with the world of the Dickensian shadowed alley peopled by Fagin-like anti-heroes coloured his outlook from childhood (it is one of the main themes of his recent The Ghosts of Oxford Street, a sanitised version of his unfinished final year project at Goldsmiths’, a psychogeographical film about Oxford Street). Through attendance at art schools, McLaren’s grasp of politics was mediated by fashion, style and appearance and reached its crystallisation and apotheosis in his participation in the sit-in of 1968 at Croydon Art School and his marginal involvement with King Mob which had fetishised both revolutionary violence and pop culture. However, by the time of the Angry Brigade trials in 1971 (a group who had bombed Biba for having manufactured lifestyles) he revealed his true colours, sidestepped into fashion and opened ‘Let it Rock’.

By this time Rock had started to be increasingly domesticated and McLaren was drawn inexorably to the world of the Teds: people who lived the style and whose clothes were a vital part of the brutal and dandified vernacular of an attractive, nostalgic, fictional underworld of London crime . The subsequent switch in McLaren’s vision from this totally retrospective involvement with a fossilised ‘conservative proletarianism’ toward a Modernist subversion of the present, arose out of his contact from 1973, with the New York Dolls who merged style with their songs and their lives, fuelled by a media attention that created both reality and, in unpredictable excess, a certain unreality. After their drummer Billy Murcia had died in unexplained circumstances they were, as Sylvain Sylvain relates, ‘a big smash ... We were living this movie: everybody wants to see it, and we were giving it to them’. It was this power, recognised by Parnes in 1956, that McLaren now looked to tap into.

Through 1976, ’77 and ’78, McLaren increasingly posed as an autocratic Debordist figure running wild with the past, manipulating a London mob, plucked from Dickens and Cruikshank, that had previously infested the sewers and that would give the lie to the national dream surrounding the coming Royal festivities of the Jubilee. For the handbill of the band’s Christmas Day 1977 concert, McLaren wrote a manifesto of sorts that he archaically signed, predictably enough, ‘Oliver Twist’:

‘They are Dickensian-like urchins who with ragged clothes and pockmarked faces roam the streets of foggy gas-lit London. Pillaging. Setting fire to buildings. Beating up old people with gold chains. Fucking the rich up the arse. Causing havoc wherever they go. Some of these ragamuffin gangs jump on tables amidst the charred debris and with burning torches play rock ’n’ roll to the screaming delight of the frenzied, pissing, pogoing mob. Shouting and spitting “anarchy” one of these gangs call themselves the Sex Pistols. This true and dirty tale has been continuing throughout 200 years of teenage anarchy and so in 1978 there still remains the Sex Pistols. Their active extremism is all they care about because that’s what counts to jump right out of the 20th Century as fast as you possibly can in order to create an environment that you can truly run wild in.’

This incredible document, which at the same time both defines McLaren’s aspirations and buries those same aspirations deep in the language of self-mythology, capturing the spirit of Punk’s ‘year zero’ and the Day of Judgement that Punk embraced. This truly was an image of the world turned upside down and an entry into insanity. And yet, if the Sex Pistols were the archetype of Punk, what did this mean? McLaren’s keenness for a Dickensian superstructure for his ‘Situationist-inspired’ creation, where the boundaries between art and life were dissolved, was more than just a colourful backdrop to his out-ofcontrol fragmented exploitation of teenage nihilism. Oliver Twist embodied the conscience of the Victorian age just as the ‘young assassins’ of Punk both shone the light on the social decay of British life and in a spirit of relentless confrontation, provocation and celebration refused to bow to the establishment. In reply to Yorkshire TV’s charge of being sick on stage and their refusal to be a ‘good example to children’, McLaren famously answered, ‘Well, people are sick everywhere. People are sick and tired of this country telling them what to do.’

The thesis of Savage’s exhaustive account of the rise and fall of the Sex Pistols is that what began as hype ‘quickly became a prism through which the present and a future could be clearly seen’. In this account, cause and effect become blurred as we ride the roller-coaster movie of McLaren and Westwood’s ‘dream academy’. The 1976 heatwave becomes a trigger for the apocalypse signalled in The Clash’s London’s Burning and White Riot (that autumn their shirts had shouted out ‘Sten Guns in Knightsbridge’ and ‘Knives in W11’). Following the change of ‘Sex’ to ‘Seditionaries’, the nature of the apocalypse was codified as it had been in the ‘Anarchy Shirt’ and in a prediliction for Nazi insignia: an ‘explosion of contradictory, highly charged signs’. 1977 saw both the fragmentation of the social and political order with the No Confidence vote in the House in March, the Grunwick Strike and the Lewisham riot. In Germany the activities of the Red Army Faction looked to the similar theoretical wellspring of late 1960s post-Situationist philosophising as had McLaren. Contrasting all this was the official fantasy of the Silver Jubilee.

However, 1977 also marked the beginning of the end of the road for the Sex Pistols when the movie speeded up and they had to start living up to and exceeding their names: Rotten better had be rotten, Vicious had to be unpredictable, threatening (as Bob ‘Old Grey Whistle Test’ Harris found out to his cost) and dangerous. The hype and the exploitation in effect became the ‘prism’ refracting back on to the Sex Pistols. So, following the press conference after their official signing to A&M there was a drunken brawl amongst themselves; ‘the fight was about who was the toughest; who was the most Sex Pistol’. Steve Jones realised that after the appearance on TV with Bill Grundy and the ridiculously scandalised reaction of the media it was different. ‘Before then, it was just music: the next day it was the media’, or as Peter Hook of New Order reminisced, ‘Punk had been completely underground until Grundy: after that it was completely over the top’. To all intents and purposes the Pistols were stuck in a rut as an unchanging spectacle, a fact made clear by their American tour. The music was now an irrelevance and the band was only capable of adding four new songs to their act by the time they split in 1978. Yet at the same time, their notoriety increased and the violence which had previously been cinematic suddenly became real and directed at the Sex Pistols themselves, as they became victims of their own history and tabloid mythology.

As Punk became even more commercially defined and emasculated as New Wave by the end of 1977, The Clash addressed the problem at the heart of the Sex Pistol’s failure. In (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais, the possibility of identifying a highly mediated pop entertainment with the authentic and primitive voice of revolt, resistance and struggle is put into question.

In the autumn of 1974 McLaren collaborated with Westwood and Bernie Rhodes to produce a manifesto T-shirt entitled ‘You’re gonna wake up one morning and know what side of the bed you’ve been lying on’. Under this was printed a list of ‘Hates’ and ‘Loves’. In the list of ‘Loves’ sandwiched between ‘Jim Morrison’ and ‘Patrick Heron v The Tate Gallery and all those American businesslike painters’ is ‘Alex Trocchi-Young Adam’. Trocchi, publisher (through his magazine Merlin) of Beckett and Ionescu, participant in the Lettriste and Situationist International and the author of Young Adam and Cain’s Book, had been a systematic user of heroin for the last 30 years of his life and was an archetype of the engagé outsider and outlaw that was later held in high esteem by the Punks. After spending the 1950s in Europe and America he returned to Britain in 1961, jumping bail in New York and so narrowly escaping the possibility of the electric chair for supplying drugs to a minor. His use of drugs, for which he was always a prophet and never an apologist, enabled him to be ‘an alien in a society of conformers’. However, it was not long after his arrival back in Britain that he entered public consciousness with William Burroughs at the International Writers’ Conference, part of the 1962 Edinburgh Festival. He admitted publicly to being a heroin addict and coined the phrase that he acted as a ‘cosmonaut of inner space’.

At the conference Trocchi elaborated on Burroughs’ statement that the future in writing lay in the manipulation of the field of space and not time. In this way narrative could be dematerialised and replaced by the assertion of the primacy of a new language of experience. To this end, Trocchi stated that ‘modern art begins with the destruction of the object. All vital creation is at the other side of nihilism. It begins after Nietszche and after Dada’. Not only were categories of practice no longer relevant but artists now, he declared, should be involved in a ‘tentative, intuitive and creative passivity. A spontaneity leading to what Andre Breton called the “found object”. A found object is at the other end of the scale from the conventional object. To free themselves from the conventional object and thus pass freely beyond non-categories, the 20th-century artist finally destroyed the object entirely.’

The reference to the Surrealists was not arbitrary but well-meant, as by now Trocchi was back in regular contact with Guy Debord who had set himself the task of re-presenting the Surrealist tenets of surprise, play and desire within the form of a fully cultural revolution and Trocchi was beginning to work on his belief in the necessity of what he was to call a ‘metacategorical revolution ‘which was suggested through heroin in a particularly lucid section of Cain’s Book: ‘For centuries we in the West have been dominated by the Aristotelian impulse to classify. It is no doubt because conventional classifications become part of a prevailing economic structure that all real revolt is hastily fixed like a bright butterfly on a classificatory pin ... Question the noun; the present participles of the verb will look after themselves.’

In 1963, during the short period in which he was on the editorial board of the Internationale Situationniste, Trocchi had published his Technique du Coup du Monde in that journal. This tract, born of the times when nuclear holocaust was an ever-present possibility, became the founding and defining manifesto of what would become in 1964 Project Sigma – the material fruits of his metacategorical revolution. The text starts with an Artaudian epigram: ‘And if there is still one hellish, truly accursed thing in our time, it is our artistic dallying with forms, instead of being like victims burnt at the stake, signalling through the flames’, the significance was that Artaud called not only for the death of the object but also for a new experiential language of the theatre which would not be a representation but be life. Artaud, like Trocchi, was not contemplating a ‘symbol of an absent void’ and, by going beyond a nihilist stance, offered positive affirmation of a new cultural and social way of living.

Given Trocchi’s central position in the countercultural underground in London in the 1960s, it is a shame that Andrew Scott decides to tell a different story: that of the Scottish writer. This is a title that Trocchi would have hoped he had escaped when he left Scotland for Europe in 1950. The literary achievements of Young Adam and Cain’s Book, Project Sigma, his teaching at St Martin’s School of Art and at the Anti-University, his formative links with Burroughs and Debord, the Lettrists and the Situationists, all that constitutes his true historical significance is largely ignored, trivialised or misinterpreted. For Scott the major event at the 1962 Writers’ Conference is Trocchi’s altercation with Hugh MacDiarmid: an event of purely local importance, but then the biography and the scrappy collection of writings are both aimed at a predominantly Scottish readership. Trocchi’s work – utopian, grandiose, and in practice sordid and largely unworkable – is bigger than all this and serves to identify the concerns of the Underground during that period of rupture in the mid-1960s, when there was an attempt to search and evolve a new language of expression and action in which the object was erased in favour of a field of political and social engagement in which artworks were felt able to concretely bring about change. Ultimately it is at this point that the work of Trocchi and McLaren diverge. The goal of McLaren’s use of a Situationist model was ‘Cash from Chaos’, the commodification of anarchy, and this puts the lie to Savage’s superb book which is ultimately flawed by the myth that ‘History is made by those who say “No” and Punk’s utopian heresies remain its gift to the world’.

- Alexander Trocchi: The Making of the Monster, Andrew Murray Scott (ed), Polygon, 1991, 182 pp, 23 b/w illus, £14.95, ISBN 0 7486 6106 9

- Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds: A Trocchi Reader, Andrew Murray Scott (ed), Polygon, 1991, 228 pp, 1 b/w illus, £8.95, ISBN 0 7486 6108 5

- England’s Dreaming: Sex Pistols and Punk Rock, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber, 1991, 602 pp, l0 col & 104 b/w ill us, £17.50, ISBN 0 571 13975 2

- Malcolm McLaren’s The Ghosts of Oxford Street was shown on Channel 4 in December 1991.

- Craig Bromberg, The Wicked Ways of Malcolm McLaren, Omnibus Press, 1991, 330 pp, 24 b/w illus, ISBN 0 7119 2488 0

- Glen Mattock with Pete Silverton, I was a teenage Sex Pistol, Omnibus Press, 1990, 192 pp, 15 b/w illus, £6.95, ISBN 0 7119 2491 0

Andrew Wilson is an art-historian and art critic.

First published in Art Monthly 154: March 1992.