Comment

Call & Response

Morgan Quaintance takes issue with the political claims made in Stephanie Bailey’s article ‘Athens: Future Past’ and Stephanie Bailey responds

CRYPTIC OBLIQUITY

Morgan Quaintance takes issue with the political claims made in Stephanie Bailey’s article ‘Athens: Future Past’

Mimetic exacerbation, mirroring, acceleration, ‘over-identification’. There are plenty of terms in our current art theoretical lexicon for the device of neoliberal or right-wing aesthetics, language and behaviours to undermine said ideologies, but strangely nobody employs the one word accurately describing that methodology and its formal results: bollocks. The idea that white artists mimicking fascists, Nazis, white supremacists, bigots and nationalists disrupts or demystifies rather than propagates (however subtly) the right positive message of an ‘irresistible rise’, or results in said targets, groups or individuals altering their behaviour, is just idiotic.

In reality, what’s repeated with brain-numbing frequency is the production of weak ‘works’ that rely on the re-presentation of aesthetics of oppression (however indirect or cryptic) for impact and affect. Yes, that strategy is used by naive, socially isolated members of demographically homogeneous groups; stupid provocateurs convinced of their own special intelligence or the value of transgression for transgression’s sake. It’s also used by people who are (however indirectly) supporting racism and engaged (consciously or unconsciously) in furthering the interests of specific far-right or racist groups – by ‘interests’ I mean the violent (physical and psychological) abuse and domination of targeted peoples, or propagation of the narrative that such a future is inevitable. What everybody should know by now is that these approaches are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they frequently come together in the single individual tittering behind a non-committal hedge of ambiguity and irony (the transgressive approach) in order to hide the reality of their participation in the second and more sinister strategy (dalliance with and support for racist and far-right groups). What beggars belief is that people still pop up to defend such behaviour in support of – and here we should all be rolling our eyes – broadening ‘the conversation’ or in the name of ‘free, reasonable and challenging debate’.

I am, of course, writing in regard to Stephanie Bailey’s blandly acritical piece on the Athens Biennale last issue. But this isn’t a ‘call out’ of the Biennale or a personal ‘take down’ of Bailey. I’m writing to address specious positions repeated in the article that are now frequently parroted. Such opinions are increasingly appearing in texts and talks supposedly taking a sober and pragmatic look at the ‘current political climate’: specifically, that fantasy territory where clear thinking has been surrendered to ‘left pedantry’, infighting, gender fluidity fetishism and, last but not least, political correctness gone mad (this century’s current top straw man). So, let’s take the efficacy of ‘over- identification’ first.

Bailey uses an unattributed quote which describes Front Deutsche Äpfel’s mirroring of the far-right as an act that combats fascism through a mimicry that causes an ‘unsettling, puzzling effect’. Such work, like that of the try-hard ‘fascist mimics’ Laibach, always depends on and responds to an outdated ‘Triumph of the Will’ image of fascism and Nazism, a stable world full of goose-stepping ideologues and Sieg-Heiling skinheads timorously sensitive to the appropriation of their cultural field by … wait for it … artists. That world doesn’t exist. Today, fascism, racism, nationalism and Nazism come together in an ever-shifting, contradictory and amorphous world of floating signifiers, confused allegiances and discrepant alliances. We are talking about a world in which fascists hide their allegiances by wearing sportswear such as the Lonsdale brand because the letters NSDA in its logo are similar to the NSDAP acronym of Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party, or where fascists wear the Palestinian keffiyeh as a symbol of ‘freedom’ and antisemitism. In other words, cryptic obliquity is the name of the game, and through it the indirect propagation of attitudes and ideas designed to surreptitiously structure the terms of public debate. That’s even before we have got to considering the cartoonish world of memes and esoterica that the alt-right favours, and individuals like Daniel Keller and Daniel Miller, Deanna Havas, Ed Fornieles and Lucia Diego splash around in (see my feature ‘Cultic Cultures’ AM404 and Larne Abse Gogarty’s ‘The Art Right’ AM405). So, overidentification: bollocks as method, bollocks as form, bollocks as a defence. Next up, the idea that ‘progressive movement(s) flounder on internal conflicts’.

Yep, it’s that hackneyed complaint of a ‘fragmented left’ collectively failing to stop bickering and unify. What Bailey (and others who parrot this false position) is doing is attempting to explain (in her own words) a ‘complex political zeitgeist’ by using the most reductive and simple Manichean model possible: a battleground between a unified right and a fragmented left. Again, this neat and discrete clash between two sides has no correlation in reality. It does not exist. Both positions are constructs, terms used for ease of reference that actually corral vastly different activities under a single word. Who exactly constitutes the left that is often referred to as failing and fragmented in that dichotomy anyway? And when was that mythical past in which all of ‘the left’ aligned to achieve a single superordinate goal?

Now what of this unified right which is, according to Bailey’s other claim backed up by zero comparative evidence, currently holding a clear lead over ‘the left when it comes to [mobilising] a wide base’. Let’s take England. Are Nick Griffin, UKIP, National Action, Stephen Laxly Lennon and the Football Lads Alliance unified? No, they’re all squabbling. How about Europe? Are Germany’s NPD, Turkey’s Grey Wolves, Greece’s Golden Dawn and Poland’s ONR unified? No, there are some fundamental ethnic differences there. What if we narrow it down to just the so-called alt-right? Do Richard Spencer and Milo Yianopolis stand united? No, homophobia is a bit of a problem. You see, the model just doesn’t stand up. Not even to the most basic scrutiny. Now, to people whose political awareness is framed by social media and the printed press – ie outlets which have a vested interest in keeping audiences misinformed and stimulated by fear – the ‘rise’ of the far-right seems an incontrovertible reality, while writers who use such language uncritically participate in the normalisation of the ‘rise’ concept and to the psychological conditioning of a reading public. There may be an increase in the visibility of disparate far-right activity (shocking for a privileged and closeted bourgeoisie unaware of how racist Europe, North America and, let’s face it, the rest of the world has always been if you are dark skinned) but it is not some heroic, Tolkein-esque ‘rise’ of a hitherto dormant unified body, and it is certainly not dwarfing efforts by the vast swathes of progressive, democratic or socialist-minded groups and individuals which are attempting to create a more open and just society and largely succeeding. But do we hear people talking with as much frequency, or with the same morbid frisson of excitement, about a rise of the left?

Finally, to the business with Luke Turner. The Athens Biennale team’s (and seemingly Bailey’s) decision that the online hectoring of Turner by Keller (and by extension Havas, assorted fake Twitter accounts, and those whose racist bigotry is overt and not hidden behind ‘ironic’, ‘transgressive’ or ‘arch’ posturing) didn’t amount to anti-Semitic signalling or racially tinged baiting is theirs to make. But it betrays an astronomical level of semiotic illiteracy and inexperience on the parts of Poka-Yio, Kostis Stafylakis, Steffi Hessler and Bailey. Even if they or you are still blindly unwilling to concede that there has been racist, anti-Semitic or prejudicial behaviour of any kind, what is clearly evident from the reams of material online is that a group of people are gleefully taking pleasure in insulting, abusing, ridiculing and intimidating another human being. Why would anyone want to support or defend this? Whatever ideological gloss you do or don’t spread over it, it is still repellently simple and irredeemable behaviour, Now, in addition to this foolishness, an exhibition in Los Angeles has been staged that names and insults Turner in the title. Seriously, people, there is nothing complex, necessary or progressive about this situation at all; it is just a dire display of humanity at its most moronic. In other words, bollocks.

Morgan Quaintance is an artist and writer.

FROM THE OTHER SIDE

Stephanie Bailey responds

I humbly accept Morgan Quaintance’s response and welcome this opportunity to speak to some of the points that were raised. The essay in question addressed an accusation of supporting fascism and anti-Semitism against the Athens Biennale by situating the institution within the political context out of which it emerged and through which it has navigated. This is an institution that has been tracking and responding to the very real rise of the far-right in Greece – indeed, its mainstreaming in often insidious yet palpable ways – for over a decade, and its sixth edition sought to highlight this development. This context was lost in a critique levelled at the Biennale from afar, which basically reduced the entire platform, and those working within and with it, to an accusation that does not hold up when considering the anti-fascist work that the Biennale has engaged in for years, nor the granular density of the exhibition itself when it comes to the people who participated in its making.

This problem of reduction can likewise be applied to the blanket dismissal of a strategy – or style – of art making, which limits the space for makers to express the nuances of their research, tactics and reasons for using them; and for their artworks to be read according to these details. Consider Heba Y Amin’s Operation Sunken Sea, 2018, which was described in Dorian Batycka’s Hyperallergic review of the 10th Berlin Biennale as ‘one of the most powerful works’ on show. The project restages German architect Herman Sörgel’s 1920s proposal to unite the landmasses of Europe and Africa into a supercontinent by draining the Mediterranean Sea. Amin describes the installation as having ‘a bureaucratic, old-world feel, with dictatorial motifs and props mixed in’. Works included a black-and-white photograph of Amin titled Portrait of Woman as Dictator I and a video in which Amin, in the role of this dictator, delivers a speech created from excerpts of those given by eight dictatorial leaders, from Benito Mussolini to Recep Tayipp Erdoğan. The project confronted ‘a masculinist, patriarchal spirit’ that Amin considers ‘fundamental to … colonialist projects and attitudes’. ‘Where does that entitlement come from, and what does it feel like?’ Amin asks in one Artforum interview; ‘I thought it’d be interesting to replicate that viewpoint, but from the other side.’

Should Amin’s work be dismissed as ‘idiotic’ for ‘rely[ing] on the re-presentation of aesthetics of oppression (however indirect or cryptic) for impact and affect?’ And what of Gabi Ngcobo’s Berlin Biennale, which showed the work in the first place – is that ‘bollocks’ too? The Berlin Biennale’s visual identity, based on the dazzle camouflage of First World War warships, communicated an important underlying logic to Ngcobo’s curating. Dazzle warships, Ngcobo explained, ‘were not camouflaged in order to be unseen, but rather to pose questions about the ways that they are seen’, and they were often attacked more. Was the 10th Berlin Biennale’s visual identity a functional example of the ‘cryptic obliquity’ that Quaintance describes, and is it safe to say that its intention was certainly not to propagate fascist ideologies, but an attempt at restructuring the parameters of tired and often binary debates? To quote Ngcobo, ‘It almost seems like we have to cultivate a practice of just being with art for a while before jumping into nervous and at times neurotic discussions about it.’

Take the unsettling double-vision produced by Jacob Hurwitz-Goodman and Daniel Keller’s 2017 documentary The Seasteaders, which was shown at Athens Biennale 6. The film focuses on the Seasteading Institute, headed by libertarian Patri Friedman and supported by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, and its ambitions to create an autonomous archipelago of manmade floating islands in the Pacific Ocean. The artists were allowed to film an Institute conference in French Polynesia – where the Seasteaders were granted government permission (later revoked) to create a prototype floating community in national waters – on the basis that their material would be shared with, and subsequently used by, the Institute. As described on the Athens Biennale’s website, The Seasteaders is a stark portrayal of the Institute’s neoreactionary adjacent politics. Days before it was due to premiere, the Institute released its own documentary with the same name and near identical trailer – a move, observed Brendan C Byrne, to ‘hijack’ the film’s search engine optimisation rating and surreptitiously suppress its critical perspective. The result is two films expressing two different positions that look very similar, but only one was intended as pure propaganda.

This split highlights the need for vigilance, especially given the fact that today, as Quaintance rightly points out, ‘fascism, racism, nationalism and Nazism come together in an ever shifting, contradictory and amorphous world of floating signifiers, confused allegiances and discrepant alliances’. I fully agree; it is this new normal that Athens Biennale 6 sketched out in order to engage its international and local publics in a broader discussion about this creeping reality, and to better recognise and respond to extreme positions hiding in plain sight. But I disagree with Quaintance’s dismissal of the observation – which is by far not a unique perspective – that ultra-conservative and far-right forces are managing to galvanise a broad, popular base in certain contexts. We have witnessed this in the US under the Trump administration, and if the Greek example is anything to go by then this trend will come to Europe – if it has not arrived already. This is something that so many living in Greece understood when the crisis took root and the international media dismissed the Greeks as ‘tax dodgers’ and ‘lazy workers’: the economic crisis, which contributed to the rise of Golden Dawn, was a global problem. Soon enough, it was.

Only a few weeks ago, elections in the Netherlands saw the governing centre-right coalition led by People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy lose its senate majority to the populist far-right Forum for Democracy, making a party that previously had no seat in the senate the largest one in an already right-leaning house. This, along with other elections in recent years (in 2017, a far-right party gained parliamentary seats in Germany for the first time since 1949), seems to counter Quaintance’s view that ‘There may be an increase in the visibility of disparate far-right activity … but … it is certainly not dwarfing efforts by the vast swathes of progressive, democratic or socialist-minded groups and individuals which are attempting to create a more open and just society.’ (In April 2018, Hungary’s far-right prime minister, Viktor Orban, won a third consecutive term in elections that saw Orban’s party, Fidesz, obtain a two-thirds majority in parliament. One year later, Matteo Salvini, Italy’s anti-immigration interior minister/deputy minister, announced a European alliance of populist and far-right parties ahead of European Parliament elections.) The current political climate is simply not so clear-cut, as Quaintance himself noted, and it would be naive to ignore the emergence of a visible opposition to ‘open’ and ‘just’ ideals in electorates across Europe, the US and beyond. (Let us not forget the recently elected far-right president of Latin America’s largest democracy.) On that note, I am in full agreement with Turner when it comes to remaining alert to such hazards.

As for the ‘mythical past’ Quaintance suggested never happened, in which ‘all of “the left” aligned to achieve a single superordinate goal’ – is this not an aim of many leftist movements, past and present? Perhaps we might also consider the conception of the left not as an all-encompassing abstraction, but as a series of granular and contextual movements connected to international histories of leftist politics. Of course, it is tricky when we use terms like ‘left’ and ‘right’ when politics seem to have shifted so much that, in some cases, the poles appear to have flipped altogether. Quaintance was quite right to call the popular terminologies that we have at our disposal to describe the political present and express political positions ‘the most reductive and simple Manichean model possible in practice’. They come from a political system that, as Quaintance writes, is predicated on opposition, thus creating, whether we like it or not, a ‘neat and discrete clash between two sides’ – a stalemate that characterised the Cold War era as much as the transnational movements that resisted the divides of the time. I also fully agree with Quaintance when he describes the positions of left and right as ‘constructs’ – ‘terms used for ease of reference that actually corral vastly different activities under a single word’. Reducing a political context, movement or position to a single word does indeed do a disservice. Especially when there is work to be done.

If the words we have no longer serve us, perhaps one way of countering the issue is to construct terms that adequately describe the political movements currently developing across the spectrum in order to manifest effective forms of allegiance, solidarity and alignment; or at the very least, devise ways of speaking with and understanding one another effectively and respectfully. Where better – in the context of the art world, at least – to think through, outline and workshop such possibilities than in the spaces that are using their platforms for exactly this purpose?

Stephanie Bailey is a writer and editor.

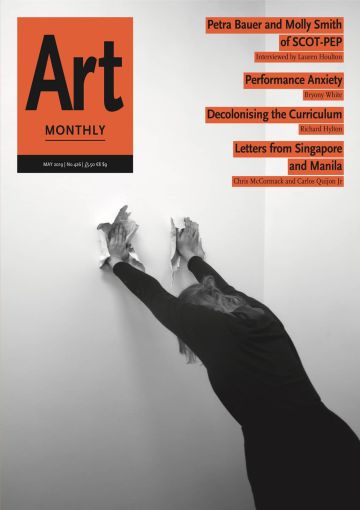

First published in Art Monthly 426: May 2019.