Feature

Bread and Circuses

Peter Scott on the mayor, the waterfalls and the art of neoliberalism

From the start, Olafur Eliasson’s Waterfalls was clearly intended to provide New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg with the second public art blockbuster of his administration. Ushered in by an enthusiastic waterfront news conference, where the mayor proclaimed it ‘the most unexpected and intriguing waterfall destination between Niagara Falls and Victoria Falls’, Eliasson’s project was also likened to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Gates, a wildly successful kitsch spectacle in Central Park that brought the city millions in tourist dollars. Opening near the end of Eliasson’s two simultaneous museum shows at MoMA and PS1, The New York City Waterfalls had something that the aesthetically questionable Gates project didn’t: the up-to-date backing of the contemporary art establishment. Largely fawned over by the cultural press, the actual experience of the waterfalls provoked decidedly mixed reviews from the public, with words like ‘anaemic’ and ‘unimpressive’ appearing frequently on local blogs – opinions occasionally countered by supporters who claimed that those who failed to appreciate the waterfalls’ beauty were philistines.

Where The Gates was sequestered within the confines of Central Park, isolated from conventional urban spaces, which allowed for a more secure theme park-type experience for those visiting from the suburbs, the four 90-120ft waterfalls encompass the East River waterfront from midtown all the way to Governors Island, vastly expanding the reach of public art. During the press conference, Bloomberg barely praised the project for its artistic merits before quickly adding how much money could be made ($55m) through tourism, making it clear that though he felt the project represented ‘a beautiful symbol of the energy returning to our waterfront’, the bottom line was never far from his thoughts. For the average New Yorker living through the largest reshaping of the city’s built environment since Robert Moses’ slum clearance of the 60s – much of it now occurring along the East River waterfront in Brooklyn and Queens – the ‘energy’ Bloomberg referred to might not seem so poetic.

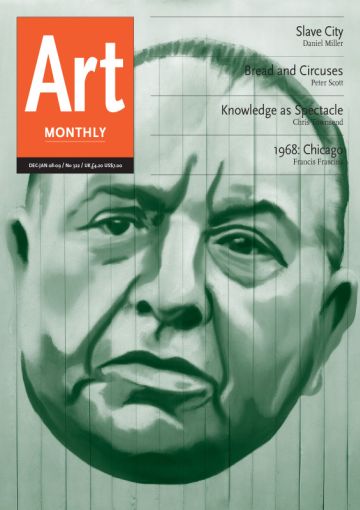

Regarded as the antidote to Rudy Giuliani for his support, rather than disdain, of culture, Bloomberg’s more patrician style contrasts sharply with the brash, take-no-prisoners approach of his predecessor, helping to veil an aggressive, pro-development assault on what were once mixed-use, working-class neighbourhoods. Recent high-profile construction accidents, including the collapse of two large cranes that caused nine deaths in the last six months (bringing this year’s total to 15), have heightened public scepticism about the out-of-control building going on in the city and, according to a recent article in the New York Times, threatened to tarnish ‘Mayor Mike’s’ carefully crafted image of a competent manager who presides over a smoothly run city government.

Into this potentially trying time for a mayor who flirted with a presidential run and, more recently, provoked controversy by circumventing a public referendum on term limits so that he might keep his job, steps Eliasson, an artist whose spectacular 2003 installation at Tate Modern, The Weather Project, drew two million visitors. While The Waterfalls was in the works for a few years, it debuted at an opportune time for Bloomberg, providing an immediate distraction in a rare moment of public scrutiny. Like most public-art-as-spectacle, which functions as a benign curiosity that presents the evening news with an amusing anecdote to close out their broadcast with, The Waterfalls’ opening day did not disappoint. News organisations around the world found the Eden-esque waterfront summoned by Eliasson and Bloomberg’s waterfall collaboration irresistible, celebrating the temporary return of an urban metropolis to its primordial splendour.

In his book, From Welfare State to Real Estate: Regime Change in New York City, 1974 to the Present, Kim Moody describes the profound socio-economic shift which occurred in New York as a result of the mid-70s fiscal crisis. Initially intending to ‘save’ a city from what many claimed to be near bankruptcy, business leaders and government constructed what Moody refers to as a ‘crisis regime’ which, through emergency measures, served to shift the balance of power between business, government and unions in favour of a newly formed business elite. Part of the process of shifting political power from public to private interests is the trend towards increased privatisation of city services, which is enhanced by recessions. As government is forced to ‘cut back’, the public sector shrinks, offering new opportunities for investment by private firms – a process familiar to Londoners. Mayor Giuliani was a major proponent, selling off a city-owned radio station and many community gardens, while privatising the welfare system. Under Bloomberg this practice has continued unabated: he recently privatised the north end of Union Square Park to accommodate an upscale restaurant and is currently using taxpayer funds to finance the construction of two new, privately owned sports stadiums.

Presiding over a city that has seen its wealth soar even as its middle class shrinks, its skyline packed ever more densely with luxury buildings as its homeless shelters are filled with record numbers of families, the mayor has managed not only to elude criticism but actually to garner praise. While Giuliani was the subject of derision for the thuggish tactics of his police force, Bloomberg’s nationwide ‘intelligence gathering’ undercover operation prior to the 2004 Republican convention (later reported by the New York Times in March 2007), which was followed by mass arrests of thousands of innocent bystanders and their prolonged illegal detention, may have raised a few eyebrows but did little to damage his image as an efficient manager of the city’s affairs. With an apolitical, no-nonsense style whose only ideology is urban-life-as-successful-business, it is clearly Bloomberg – not Giuliani – who best understands the most effective way to further the neoliberal model, which favours private access to government over broad-based public influence. With his enormous wealth (assessed at $20bn), Bloomberg benefits from the public perception that he cannot be bought. Rivalling Bill Gates in his philanthropic reach, Bloomberg’s cultural influence far exceeds that of most politicians. With the public focused on the Mayor’s benevolent use of his fortune, the billions of dollars in tax breaks granted to developers by the city at the expense of its residents occurs with little fanfare. And when these tax breaks are questioned – which is rarely – they are claimed to be necessary for economic stimulus.

In a 2003 event described in Moody’s From Welfare State to Real Estate, a construction industry group – known as the New York Building Congress – sponsored a tugboat tour along the East River waterfront, including many areas of Brooklyn and Queens that have since been rezoned for major development. Daniel Tishman of Tishman Realty and Construction told the city officials and real estate/construction industry leaders present that ‘New York’s waterfronts are indeed a new frontier, and the East River waterfront contains some of the best locations (for development) left in the city’. The Waterfalls project received support from Tishman Construction as well as Forest City Ratner, one of New York’s biggest developers. The two companies have vested interests in the city maintaining its current mega development-friendly climate. Forest City Ratner is currently using eminent domain, a process whereby the government can seize private property ‘for the public good’, to remove tenants living on property it hopes to acquire for its Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn, one of the largest urban developments in decades and featuring plans by starchitect Frank Gehry (who also designed Serpentine Gallery’s latest pavilion in London). While New York was in the midst of a building boom of unprecedented scope, and developers were wanting to ‘make hay’ while the economic climate was good, so many projects overlooked basic safety concerns that New York City witnessed an 83% increase in construction accidents in the last year. Tishman Construction’s record reflects the city’s conspicuous lack of oversight; in the last few years, large panes of glass, metal studs and other debris have been flying off their projects seriously injuring some, while others (a cab driver whose cab was cut in two by a four-ton steel section of a crane’s rigging) have miraculously escaped harm.

Partnering with Eliasson to facilitate his trademark approach of making the armature for his effects visible, Tishman engineered the massive scaffolding to support the waterfalls that, the artist claims, ‘is not an unfamiliar structure in New York’: ‘You see it on every construction site in the city. I want people to know that this is both a natural phenomenon and a cultural one.’ It is hard to know what more a developer could ask for. Not only has Tishman added a robust-looking, digitally enhanced ‘Waterfalls’ to the ‘Arts and Culture’ page of its website, and filled its ‘In the News’ section with glowing reviews of the waterfalls, but the artist himself has characterised scaffolding, a ubiquitous material contributing to the increase in noise, chaos and, more recently, fear engendered by the biggest building boom in decades, as a ‘natural phenomenon’. With a thin veil of water cascading in front of these massive steel supports, positioned in key areas of the waterfront that are undergoing major development, the artist successfully aestheticised a material that facilitates drastic change within the urban environment.

When describing the rationale behind situating his piece along the waterfront, Eliasson claimed that throughout history [New Yorkers] have always taken water for granted adding: ‘Now people can engage in something as epic as a waterfall, see the wind and feel its gravity. You realise that the East River is not just static.’ Revealing a profound gap between the language museum audiences might encounter and the everyday experience of New York’s residents, these kinds of statements, when broadcast in the local news media, seem more patronising than revelatory.

But Eliasson has a job to do, and part of this job is about exposing the perceptual lack in his prospective audience. With perception as his primary focus, Eliasson’s projects intend to prod the viewer into greater self-awareness: ‘seeing yourself seeing’, as he often puts it. Underlining the relationship between the mechanisms used in his work to create an effect, and the effect itself, the devices are always made visible, providing the viewer with transparency rather than sleight of hand. Wowed by the experience of a curtain of glistening water drops in Beauty, 1993, we can step back and see the lights and hoses that produce the magic. In projects that employ mirrors, the viewer is more obviously incorporated into the work, but the distancing ‘wow’ factor remains. In Take Your Time, 2008, a piece at PS1 which consists of a large rotating mirrored surface hung from the ceiling, the audience lay on the floor and marvelled at a huge, spinning disc that reflected their image. Understanding their significance as the necessary ingredient to complete the artwork, the viewers look up in awe at their reflection, placing the work both literally and figuratively above them.

Texts accompanying the exhibitions at MoMA and PS1 assert that the phenomenological experiences prompted by Eliasson’s work bring political agency to the museum visitor. Borrowing from the ‘Light and Space’ artists of 1970s California, James Turrell and Robert Irwin (‘perceiving yourself perceiving’, once associated with Irwin, has now become Eliasson’s ‘seeing yourself seeing’), Eliasson constructs sensory experiments with light or changes the space itself, adding the natural phenomena of water, fog, moss, etc, which are biographically relevant to his native Denmark and Iceland. The time-based nature of 360 room for all colours, 2002 – a polychromatic cyclorama subtly changing colours every 30 seconds – invites viewers to gather, lending the work sociability. Mixing the contemplative mode of perceiving a blank, colour-tinted scrim (a Turrell/Irwin hybrid) with a crowd of lingering spectators, this piece reveals a contradiction between emancipating the viewer from the sensory manipulations of late-capitalist consumer spectacle through a heightened awareness of their perceptions, and the conviviality associated with relational aesthetics, which promotes the notion of community.

The mirrored pavilions of Dan Graham, an artist with whom Eliasson’s work is also associated, and who is often facilely adopted by relational aesthetics supporters, negotiate a far more complex set of perceptual experiences. When experiencing the layered opacity/transparency of the two-way mirror surface in Graham’s pavilions, the viewer must navigate the uncertain relationship between their temporarily isolated contemplation and the inevitability of their social self when encountering others in the piece. Placing far fewer demands on his public, the experiential aspects of Eliasson’s work are offset by the artist’s Oz-like presence via the techno-fetishism of the utilitarian structures that deliver it. Full of funhouse props and implicit instructions for the public to follow: ‘lie on the floor and look up at your reflection’ (Take Your Time, 2008), ‘stand in line for a mind bending perceptual experience’ (Space Reversal, 2007) and ‘wait patiently while a large, square, hanging mirror lit by a spotlight rotates in front of you’ (Wall Eclipse, 2004), Eliasson’s work successfully channels the consciousness of his audience. A question rarely posed critically is: ‘to what end?’ The neo-60s and 70s ‘green’ ambience of the work suggests a progressive ideology, but the perceptual experimentation often functions as an end in itself, and seems more about making sure your visit to the museum provides relaxation, a kind of Soma or Prozac to take for reassurance in troubled times.

The artist’s repeated use of the pronoun ‘your’ in his instructions is intended to remind viewers of their significant role in his work and further a realisation of their subjectivity, which might lead to more questioning of the manipulations of commodity culture. Outside the museum, lifestyle culture surrounds us with demographic models that, through the branding of identity – ‘iPhone’/‘YouTube’/‘MySpace’ – create the illusion of meaningful participation in a larger group while offering the uniqueness of the (constructed) individual’s identification with their brands. As we surrender to the seductive naturalism of Eliasson’s work, scepticism regarding our perceptions instead gives way to passive engagement, ‘take your time’ – typical of consumer behaviour. Employing feel-good elements of the sublime through the use of natural phenomena, perception is associated with naturalism, an apolitical, a-historical condition that, like the weather, means all things to all people. Rather than challenge the museum establishment, these reconstructed natural environments soften the hard edges of its aggressive packaging of culture, veiling any meaningful connections between cultural institutions and the social and economic status quo.

In securing an artist who enjoys critical acceptance from the cultural establishment while achieving blockbuster status through the enormous crowds that flock to his work, Mayor Bloomberg has curated the ideal candidate to join in his campaign to pacify New York. Gracing the East River waterfront with not one but four magical fountains that promise harmony over discord, the Mayor’s ambitions are matched only by the artist’s, whose work seems uncannily appropriate for a city in the midst of a drastic reshaping of its environment. Running roughshod over many communities in its preference for the needs of luxury developers, while putting the public at risk, the Bloomberg administration must now manage the chaos that its freewheeling rezoning has wrought. As the city’s residents react with fear and anger over lethal construction accidents that reveal an obvious disregard for their safety, an artist and a mayor unveiled their developer-sponsored ‘green’ art project, refocusing our attention at just the right moment to an imaginary ‘natural’ New York City in which we all may find solace.

Peter Scott is an artist, writer and curator based in Brooklyn, NY.

First published in Art Monthly 322: Dec-Jan 08-09.