Feature

Babe Power

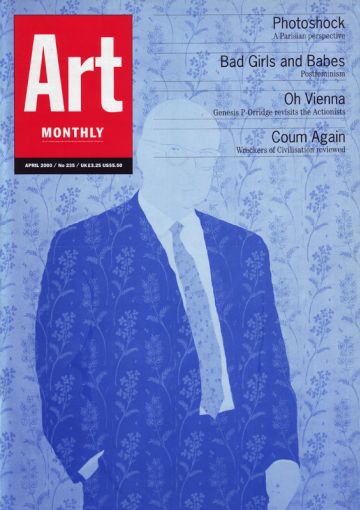

Bad girls or babes – Barbara Pollack on postfeminist art

Q: How many Bad Girls does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: One, and she really wants to get screwed!

In 1974, artist Lynda Benglis ran an advertisement in Artforum. In the ad, she posed as a Playboy centerfold wielding a gigantic double dildo. ‘Extreme vulgarity’ cried five Artforum editors, who published a joint letter in protest, condemning the photo as ‘a mockery of the aims of feminism’.

But feminist critic Lucy Lippard defended the image. To her, Benglis made clear what every woman artist knew intuitively – that all you needed to make it in the art world is a seductive stance and a big fat prick.

Two generations later, Lynda Benglis’ revolutionary pose has turned into the sure-fire career path for younger women artists. Under the banner of Bad Girls, artists such as Lisa Yuskavage, Vanessa Beecroft, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Pipilotti Rist, Anna Gaskell, Justine Kurland and Cecily Brown (to name a few) are showing off in museums, top galleries and international biennials. The work itself – and the pervasive use of nudity – is no longer shocking. What is shocking are the venues. Halls of art history that until recently ignored women artists have opened their doors and welcomed these power babes. But any artist without Alzheimer’s disease knows that this is not the first time women artists have been celebrated for selling the female nude. And many worry that this latest work is merely a replication, rather than redefinition, of the uncritical commodification of women in popular culture.

When the New Museum in New York held the ‘Bad Girls’ show in 1994 (shown also at the ICA London), many championed the term as well as the new wave of feminist art filled with humour and irony. ‘I never took offense for one minute’, states performance artist Martha Wilson, ‘it was clearly being used to subvert the idea that only boys were permitted to be bad’. According to Deb Kass, one of the artists included in the 1994 show, the term at the time seemed mildly amusing, ‘it had an advertising kind of quality, not without humor’. But the repeated use of the term in the year 2000 troubles Kass as ‘being ahistorical’. As she says, ‘The term is used again and again and again, because nobody knows their feminist history, so feminism gets invented again and again and again’.

Others are far less generous: ‘Bad Girls, as a term, acts to infantilize as well as pseudo eroticize the art and the artists, it claims to champion’, wrote critic Laura Cottingham in 1994. Today, she simply calls such work ‘Twat Art’, arguing that ‘it is really upsetting that the dominant legacy of 1970s feminism in mainstream art is the art of the striptease’.

‘The term Bad Girls is the commodification of a much tougher, stronger transformation that has occurred in the culture’, states Carolee Schneemann, the recognised pioneer of redefining sexuality from a feminist perspective. Back in 1963, when only Vito Acconci , Donald Judd, Carl Andre and the rest of the boys could get gallery shows, Schneemann flaunted convention with a series of body-based per-formances that insisted on a vaginal alternative to penile traditions. The response? ‘The reaction of curators was that this is really junk, you don’t even belong in the art world’, relates Schneemann. In 1976, Schneemann offered her response to this rejection – Interior Scroll – a performance in which she spooled out a script from her vagina. The text contained the words of a male filmmaker who rejected Schneemann’s work as art, though finding her personally attractive and charming.

Schneemann still feels the sting of patronising remarks and initial rejection. But – ever the theorist – she worries more about a generation of younger women artists who do not even notice that they may be being patronised. ‘The type of rejection I experienced made me even more determined to enter the artworld’, she explains, ‘but it wasn’t calculated the way much of the work is calculated now.’ To many of the women artists who have been labelled ‘essentialst feminists’, the success and the self-congratulatory behaviour of the current crop of women artists may be part of the problem and an example of the seamless web of commodification.

‘We saw what happened to feminist artists – they were punished or ignored – so it was natural to look for another way to go about getting the message across’, explains Joan Semmel, another 1970s pioneer. Though Semmel is enjoying a revival of attention for her paintings of copulating couples, captured from the female’s point of view, she does not identify with the current hype for such work.

‘One so-called solution to being labeled a feminist has always been this ironic position which permits the misogynist and the artist to live side-by-side in the same work.’ Pointing out that irony is ultimately apolitical and undivisive, Semmel insists on its advantages for marketing contemporary art by women. In other words, irony proved a boom to art dealers who can now peddle works by women artists to sexist and politically-correct collectors alike.

lf this position seems cynical, can it be any more cynical than Vanessa Beecroft’s performance Show held at the Guggenheim Museum in 1998? Show stationed 20 models in the rotunda of the museum, either nude or semi-nude. (The shoes and panties were supplied by Tom Ford of Gucci.) According to Beecroft, the work is her exploration of the way women skilfully ‘internalize aesthetics’. Or as Pipilotti Rist stated in a recent television interview, ‘lt doesn’t matter if the girl is naked or not. All that matters is whether she looks self-confident or happy without her clothes on.’ (A savvy pornographer couldn’t state it more succinctly.) And as recent articles in the New York Times, Vanity Fair, Vogue and Mademoiselle prove, Bad Girls are best when they themselves look like fashion models – no blacks, dykes, or 40-plus year-olds need apply. ‘Today, the word Bad means good, usually good photo-op’, confirms Wilson, ‘It does not mean addressing life-altering or deeply disturbing issues.’

Of course, no one wants to return to the bad old days of ‘Fem vs Feminist’ on the issue of sexual imagery. Almost everyone is tired and exhausted by the censorship tactics of the likes of Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin. ‘Being a post-sex feminist in 1989, before Madonna, was almost a crime’, states Marilyn Minter, whose appropriation of pornographic images was roundly excoriated in the early 1990s. ‘I was treated like a traitor to feminism because l wasn’t saying that all sexual imagery was bad.’ Minter – and a wide range of women from Hannah Wilke to Karen Finley – suffered through this period being accused of narcissism, self-promotion, and worse yet, collusion with the male gaze. No one really wants Emin or Lucas or Sam Taylor-Wood to suffer a similar fate. But many wish they would give a nod to Mary Kelly or Sylvia Sleigh or Faith Wilding or Adrian Piper – all of whom created remarkably similar works 25 years ago. Instead, more often than not, they distance themselves from identification with feminists, assisted by the term Bad Girls.

Why do women continue to embrace this label? ‘Because this is a maladaptive way of our dealing with our desperation’, says Cottingham. ‘it indicates that women still feel that they have no right to refuse institutional support.’ Schneemann offers a more long-range point of view: ‘Sometimes, the culture can accept what it rejected initially, but with that acceptance comes vitiation.’ As she points out, in a society that worships Madonna and Courtney Love, the body is no longer the difficult issue nor does it challenge political hierarchies. ‘Political issues are kept completely at bay because of the luscious promise of rewards and success if you can be a Bad Girl.’

The risks, however, are patently clear. Sure, you get fame and fortune in the short run but, as anyone scanning the XXX section in the video store can tell you, the title Bad Girls rests on the belief that women have a sado-masochistic desire for punishment. Bad girls are sexually active girls in need of discipline. Bad girls are little girls in need of a spanking. So, for now, crawl up in the lap of Larry Gagosian and Charles Saatchi. But don’t forget – the inevitable whack on the butt is on its way!

Barbara Pollack is an artist and writer living in New York.

First published in Art Monthly 235: April 2000.