Feature

Art v the Law

Colin Perry discusses protest art that uses the law as an artistic medium

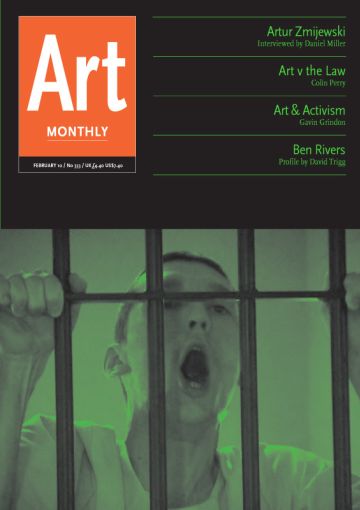

CADA, Oh, South America!, 1981

When an elected government starts issuing decrees of blatantly authoritarian pettifoggery, you need a back-up plan. One apt response is satire, another is street-level protest; but rarely do the two go hand in hand. In 2006, a friend of the comedian Mark Thomas was picnicking on the lawn in front of the Houses of Parliament when a policeman approached her: she would have to move on or she would be arrested. Why? Because the fancy pink-and-white confection she was about to tuck into was iced with a small peace symbol: it was a fondant of dissent, a cake of complaint, and an illegal act.

Under section 132 of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act (SOCPA), 2005, protesters must obtain a licence in order to demonstrate within a one-kilometre radius of Parliament Square, effectively insulating our elected representatives from the roar of street politicking. Outraged and amused, Thomas organised a series of absurdist protests, deliberately creating a mountain of paperwork for the police. Ultimately, Thomas performed a stunt that got him into the Guinness Book of Records: he gained police sanction for 21 protests in one day, each held in a different location within the restricted zone and each protesting a different non-issue, from the wonderfully apt ‘Cut Police Paper Work!’ to the anachronistic ‘We want Trolls!’ at Lambeth Bridge.

The treatment of the law as a pliable medium has long been at the core of political activism: one protests in the hope of making a change. In recent years, legality has also become a medium within contemporary art. Mark Wallinger’s famous response to SOCPA, State Britain, 2007, was a case in point. State Britain played upon the possibility that Wallinger, in relocating protester Brian Haw’s long-standing demonstration at Parliament Square to Tate Britain, which was within the putative one-kilometre radius covered by the act, was breaking the law (Reviews AM304). Maps of the zone show otherwise: the area covered by Section 132 actually ends just north of Tate Britain, on Thorney Street. Perhaps Wallinger’s work was a little underhand but, as an artwork, it nevertheless gained its frissons from the possibility of a specific legal transgression.

A similar activation of a juridically sensitive site is Kristina Norman’s installation After-War, 2009, a study of the conflict surrounding the removal of Tallinn’s Soviet-era Bronze Soldier Monument in April 2007 by Estonian officials, which was shown at the Venice Biennale and more recently in ‘Re-Imagining October’ in London (Reviews AM331). The removal of the monument, which was disliked by many Estonians due to its parity with the Soviet occupation, prompted the country’s Russian minority to take to the streets in two nights of rioting. On 9 May 2009, the day Russians traditionally celebrate Victory Day, Norman replaced the missing statue with a full-size golden replica. In her video work documenting the event, we see Estonian police confiscate the replica, load it into the back of a truck and drive off. Their actions might seem like a further layer of cultural censorship, and this might be so, but it should be noted that After-War, like State Britain, is not exactly as illegal as it seems. In this case, the Estonian president Toomas Hendrik Ilves had, two months earlier in February 2007, vetoed as unconstitutional a bill introduced to parliament by Estonian nationalists that would have banned all such monuments to socialism. The police action against Norman’s piece was, therefore, due to the imagined possibility of further ethnic violence, not a dispute with an existing piece of legislation.

Legality as an artistic medium is a quagmire, but there are quite a few artists who don’t mind getting muddy. Indeed, a key facet of artworks that treat legality as a medium is the annexation of official responses into the very fabric of the piece. At the 2009 Havana Biennial, Cuban artist Tania Bruguera staged an untitled performance event in which members of the public were allowed to take to the podium and make speeches for one minute each. It was an opportunity for the expression of free speech that was not missed by participants, who shouted ‘Libertad!’ and ‘One day freedom of speech won’t be performance art!’ (as quoted in Claire Bishop’s Biennial report in Artforum, summer 2009). Immediately afterwards, the organising committee of the Biennial issued a statement repudiating Bruguera’s event as an attempt to ‘strike a blow at the Cuban revolution’. Commentators have noted that without this official response, Bruguera’s work might seem like a merely decorative adjunct to the Biennial. Similar tactics of artistic transgression appear in a broad spectrum of artistic practices, including those of Minerva Cuevas, Sinisa Labrovic, Ivan Moudov, Oliver Ressler and Santiago Sierra. Of course, artists can easily seem callow if they are seen to stir up trouble as merely self-aggrandising stunts, and this has certainly been the case with Bruguera, who in August 2009 gained a degree of unwelcome press notoriety when she handed out cocaine at a performance in Bogota. Yet, within Cuba, her work has been interpreted as a real challenge to oppressive governance and a stance in favour of freedom of expression that seems almost alien to our already expression-saturated capitalist culture.

Bruguera’s practice has emerged against a backdrop of authoritarian government, and is infused with both resistance and romance. In order to clarify her position, I want to trace a brief history of neo-avant-garde artistic intervention in South America, specifically drawn from Chile in the late 1970s. When a US-backed coup overthrew the Marxist presidency of Salvador Allende in 1973, Chile’s artistic community reacted in a flush of activism that still resonates today. The art group Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA), which consisted of artists Lotty Rosenfeld and Juan Castillo, sociologist Fernando Balcells, poet Raúl Zurita and novelist Diamela Eltit, was a small guerrilla-like outfit established in 1979 that sought to publicise the left-wing cause and proffer specific political critiques of Augusto Pinochet’s regime. On 12 July 1981, CADA organised an action entitled Oh, South America! in which six light aircraft dropped 400,000 flyers over Santiago de Chile. These texts protested against the government, demanded a better standard of living and called – in a typically neo-avant-garde register – for new forms of art and life. In 1979, Rosenfeld created her famous work A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement, in which the artist transformed road markings into crosses by simply adding a lateral dash of white paint. The Chilean critic Nelly Richard has labelled the poetical actions of the Chilean neo-avant-garde as ‘a semi clandestine position that aimed to transform historical defeat into a rite of survival’. Dissenters were not long-lived in 1970s Chile, and artists were no exception; artist Guillermo Nuñez, who was tortured and finally exiled due to his protest art, learnt this the hard way. Nevertheless, there is hope in CADA’s actions; the ‘survival’ hinted at here is not simply bodily or individual, but also ideological and political.

The issue of hope within these ‘rites of survival’ – a hope grounded in achievable or possible aims – distinguishes such art from more nihilistic artistic ‘transgressions’. In contemporary China, the extended reign of totalitarian government and the lack of a left-wing democratic antecedent (such as Chile’s) has had specific effects on artistic dissent. For example, in 2001 the Chinese Ministry of Culture issued a communiqué prohibiting performances that broadcast ‘pornography, superstition and violence’. Organisers of exhibitions faced jail for three years for ‘erotic’ exhibitions and up to ten years for ‘more serious crimes’. The latter category includes the use of human corpses – a real possibility in a country in which exhibitions such as ‘Corruptionists’, 1999, ‘Life and Culture’, the same year, ‘Food as Art’, ‘Useful Life’ and ‘Man and Animals’, all 2000, featured works that incorporated human body parts, severed heads and, in one case, the corpse of a child. Charles Merewether, an art historian and curator of the 2006 Biennale of Sydney, has interpreted sensationally provocative Chinese works by artists such as Sun Yuan & Peng Yu as ‘a means of mobilising and registering the body in order to document an experience that has lost its power of agency’. Like Richard in Chile, Merewether calls such works ‘acts of survival’, but here the work is directed against a culture that has switched from collectivism to mass commodity consumption without pausing to register the human costs. There seems little hope here that bodily survival might be translated to anything greater.

Hope for change is the core of activism, and this might be more likely within more porous systems of government. In his fascinating study Art and Revolution, 2007, Gerard Raunig traces a ‘long century’ of art’s interrelation with revolution within a predominantly western European paradigm. Much of this investigation, which spans Gustave Courbet’s role in the Paris Commune of 1871 to Vienna’s VolxTheatre group in 2001, is concerned with what might constitute an effective combination of art and political action. In his analysis of the Viennese Actionists, Raunig concludes that the movement did not constitute a vehicle of change or agency because it failed to make the leap into the public sphere, confining itself to performances in the relative safety of universities and specialised art events. Raunig’s crowning example here is the VolxTheatre, a troupe of activists who sought to engage with local communities through street theatre, and who were famously arrested at the Genoa G8 protests in 2001 on spurious charges of violence – the evidence for which was their juggling equipment. Raunig’s examples are instructive: they demonstrate various ways through which art has previously activated a political public; he also suggests a future model that goes beyond the avant-garde top-down hierarchy of groups such as CADA to one based on a post-Operaist notion of the ‘multitude’: a broad grassroots form of continual rebellion.

Raunig’s account, however, indicates deeper problems with recent post-Soviet attempts to reformulate an image of revolution that might not be coterminous with totalitarianism. One significant problem with Raunig’s theoretical standpoint is that it is indirectly self-contradictory, because by redefining ‘revolution’ as an act of continual resistance, in a Deleuzian and Operaist mode that eschews the mantle of state power, he is effectively arguing against revolution. Structurally, both militant terrorism and legal forms of petitioning appeal to existing government powers to effect the changes they demand. Most effective activist groups, such as Greenpeace, work through multi-pronged channels of official, semi-official and illicit activity to negotiate specific ends. By contrast, theoretical radicalism today often seems more self-directed, as if designed primarily to give participants a sense of self-worth. Secondly, the question of whether revolution is indeed desirable is also debatable. Raunig falls rather too easily for what Isaiah Berlin once called the political illusion of the ‘society of saintly anarchists’. In his influential essay ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’, 1958, Berlin argues that this is a vision held by all models based on a belief in a final stage of human harmony – from the ‘reason’ of the free market to the Marxist doctrine of the withering away of the state. Such faith-based concepts can have devastating consequences for real politics. The hope that a revolution will sort out all your problems is not dissimilar to believing that ‘regime change’ will free the world of terrorism.

I recently attended a debate held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, themed under the rubric of ‘hope’, in which the political theorist Chantal Mouffe professed a desire to carry forth the torch of radicalism through the furtherance of the Marxian project influenced by psychoanalysis and Operaist philosophies. Mouffe is a canny political theorist who has clearly read Berlin as well as other key contemporary liberal writers such as John Rawls, whose epic and highly influential A Theory of Justice, 1971, reinjected the concept of ethics into political philosophy. Mouffe is a keen critic of political liberalism: for her Rawls eschews the psychological needs of people, lumping them together into an impossible ‘consensus’ (Berlin, from a realist standpoint, would no doubt agree). Yet her criticism is both negative, in offering no alternative ethical platform, and vague, in its vision of an alternative. Similarly, at another conference on ‘radical thinkers’ recently staged at Tate Britain, a panel consisting of Terry Eagleton, Simon Critchley, Kate Soper and Eyal Weizmann vacillated over the core issues of politics today. Personally, I can see no hope in self-proclaiming radicalism unless one has a better grasp of what is valued ethically and how exactly these values might be given public validity.

The type of art I have been discussing operates in exactly this way: it seeks actual alternatives without recourse to an overburdened revolutionary impulse or a deracinated radicalism. It inhabits and levers open cracks in the law, and seeks to reveal this to a broad audience – to what you might call the ‘public’. Within the pages of Art Monthly there has been a debate about the correlation between the public sphere and public artworks (see Dave Beech in AM329 and Mark Wilsher in AM331). Beech questions whether ‘public art is still feasible today’ and proceeds, via Jurgen Habermas’s theory of the public sphere, to conclude that the ‘spatial idea of the public puts the cart before the horse’. Indeed, ‘the public is not to be found on the street’; rather, it is ‘the performative activity that fills these places with public life’. Extending this analysis, Wilsher concludes that the ‘agora’ idea of the public is a redundant one: public space is here equated not with the body but with the mass of information distributed, via the internet, newspapers and TV. There’s some mileage in this idea, especially in the context of public sculpture that turns a blind eye to the people who must circumnavigate it. This is true not only of works by Richard Serra, but also of art activism that fails to note the multiplicity of public opinions and the specificity of a site. For example, in September 2003 the ‘hactivist’ collective 0100101110101101.ORG (Eva & Franco Mattes) re-branded one of Vienna’s main historic squares, Karlsplatz, as ‘Nikeplatz’. By situating an official-looking pavilion in the corner of the square and creating a believable-looking design proposal for a sculpture of a giant Nike ‘swoosh’ logo, the project was bound to cause a ruckus. Predictably, the Nike Corporation threatened legal action. But what exactly was Nikeplatz contesting? Was it a protest against copyright or against the very notion of corporations? What might it have achieved? And are the Viennese really so gullible?

Nevertheless, for all the acuteness of their arguments, I think that Wilsher and Beech overstate the case by denying the spatial aspect of the public sphere. Our bodies still occupy real space and, as a culture, we have naturalised the idea of the street as common ground. The disquieting sensation of walking out of Canary Wharf tube station on to private land policed by private security guards strikes me, like many people, as an abuse of this public arena. Artworks that engage with legality use these spaces as an agora in order to promote discussion about issues of common interest: the law, the government, the nation state and corporations. In the text referenced by Beech and Wilsher, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 1962/89, Habermas intentionally erodes several semantic differences of the use of ‘public’ in order to construct his analysis (‘public space’, ‘the public’, the ‘public interest’). However, while he suggests that the king’s bedchamber may have constituted an early proto-site of the public sphere, it was hardly an accessible arena. Surely the term ‘public’ cannot be reduced in spatial terms without becoming absurd: it would be like searching for a ‘public sphere’ between Joseph Stalin’s hypothalamus and his nose. Neither can it be migrated wholesale to the internet, TV or newspapers, for the simple reason that our bodies remain physical entities negotiating real space. We walk around, and as we do so we experience encounters that moderate our concepts of human justice, fairness and freedom. It remains both intuitive and practical to assert the street as a site in which societal values can be contested. I think artists, activists and comedians are ahead of the game here, incorporating legality and publicity into the core of their work as a medium to be worked with like clay.

Colin Perry is a writer and critic based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 333: February 2010.