Feature

Art & Oil

Colin Perry on the greasing of the art industry

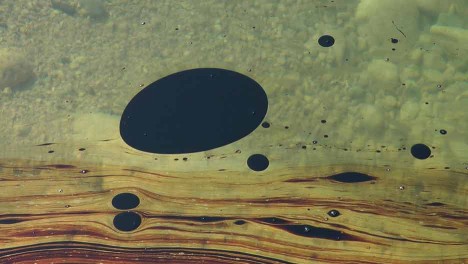

Nasrin Tabatabai & Babak Afrassiabi Seep 2012

How public are national galleries and museums today, and what exactly is the cost of the private sponsorship of public art? It is a case as slippery as the business interests of the chair of the Tate trustees, Lord Browne of Madingley, a former chief executive of British Petroleum, and as brutally extra-artistic as the arms dealers, money launderers and property speculators who patronise, and to an increasing extent own, the UK’s public institutions. Certainly, the ‘bad’ money that props up our public institutions is a disgrace.

Whether art, as currently manifest in large institutions, can do without it, is moot. In the case of Tate, campaigners have pointed out that BP’s sponsorship is easily dispensable – the corporation gives a fraction of the figure Tate members give in annual donations (since Tate does not disclose donations, precise figures are hard to calculate, but it has been suggested that BP donates something like £500,000 per annum, while Tate members give around £5m). Spokespersons for Tate defend such patronage, stating that while BP has been convicted of criminal actions (notably, in the Gulf of Mexico), it is not itself an outlawed organisation and thus accepting money from the corporation does not constitute a violation of the Tate’s ethics policy. This present article is not, however, principally about Tate or the other public bodies supported by BP (the British Museum, the Royal Opera House and the National Portrait Gallery). Rather, it is a ‘zoom out’ that takes in the long history of corporate – and particularly oil corporations’ – support of the arts in its broadest sense. In doing so, I hope to cast some light on the fact that corporate money runs deep in the arts, and that it belongs to a pattern of patronage designed to control dissident voices within the cultural sector.

The petrol, oil and gas industry’s sponsorship of art has a long history, and is perhaps most forcefully visible for what it is – propaganda – in documentary films produced since the 1920s. British Petroleum and Shell were key agents in sponsoring the production of documentary films in the UK through the 1930s onwards, and key exponents of the classic documentary tradition in the UK embraced funding from the oil industry. For John Grierson, the founding father of documentary in the UK, the ‘sponsored film’ was morally and aesthetically superior to mainstream fiction cinema. Interwar documentary in the UK was contrasted with Hollywood cinema in form, content and funding: it was to be educational, edifying, and was not necessarily expected to make profits at the box office. Funders included the British Empire itself (the Empire Marketing Board), the vast sprawling bureaucracy of the General Post Office (the GPO, which operated both the post and telephone systems, and was the largest employer in the UK during the interwar period), and later the Ministry of Information’s Crown Film Unit. By 1937, industrial sponsorship came from oil corporations (Shell Marketing and Refining Company, Shell Mex, British Petroleum and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company), gas (British Commercial Gas Association, London Gas, Light and Coke Company), shipping (Orient Shipping Line), airlines (British Imperial Airways) and the Ceylon Tea Propagation Board. Several of these groups had their own film units: the Shell Film Unit was founded in 1934 and is still in existence today, lasting considerably longer than the more famous GPO Film Unit (1933-40). The documentaries they produced were often overweeningly condescending – the first decades of documentary production in the UK was the era of the ‘voice of God’ narrator: a posh off-screen male voice telling the viewer that problems such as slum buildings (Housing Problems, 1935) and urban dirt (The Smoke Menace, 1937) can be solved by the industries that have commissioned the films.

Sponsored documentaries were also entertaining, beautifully filmed and produced, and often highly innovative (Housing Problems includes striking interviews with tenants using synchronised sounds). Such films embraced the notion that the documentary film was an art form. Watching documentaries made in this classic era, it is easy to feel charmed, amused and surprised at the range of works produced. Len Lye developed extraordinary animated films for the GPO (Rainbow Dance, 1936) and Shell (Birth of The Robot, 1936); he is awarded the status of an ‘artist’ of the film medium today, with a retrospective exhibition at the Ikon in Birmingham in 2011. Other key animators associated with GPO include Norman McClaren and Lotte Reininger. But the association between documentary and art goes further: the painter William Coldstream directed the amusing The Fairy of the Phone for the GPO in 1936; he also co-founded the Euston Road School in 1937, was vice chairman of the Arts Council (1962-70) and helped reshape art education in the UK. Nevertheless, if what they produced was ‘art’ (as Grierson himself claimed), they were clearly at the service of their sponsors. Through association with a mass-cultural art form (film/cinema) and an experimental group of filmmakers, sponsors could claim to be part of that progressive moment of Modernism in which the exploration of land for oil, and the betterment of society in general, had its corollary in the progressive nature of the Avant-Garde art itself.

In confronting the corporate ‘art-wash’ enacted by BP and Shell today, we should not be particularly surprised that mass spectacle and art are still conjoined: Tate, the British Museum, the Royal Opera House and the National Portrait Gallery draw huge crowds, and they all have high cultural prestige. This engagement is a deliberate public relations strategy that has long understood the power of patronage in the manufacturing of consent. Edward Bernays, the ‘father of public relations’ and the nephew of Sigmund Freud, had unleashed his psychoanalytically inflected model on the world by the 1920s and would later speak of his technique as a process of the ‘engineering of consent’. Bernays was adept at riding the coattails of progress: an early campaign was the pro-smoking drive directed at women, in which he rebranded cigarettes as ‘torches of freedom’, invoking the tobacco industry as a supporter of the suffragette movement. Public relations was institutionalised in documentary film in the first half of the 20th century and is associated with key figures: Jack Beddington was a PR man for Shell-Mex and BP (where he commissioned artists such as Paul Nash, John Piper and Graham Sutherland to produce artworks promoting the industry), as well as the Shell Film Unit and the Ministry of Information Film Division; Colonel HE Medlicott was PR man for Anglo-Iranian Oil; Alexander Wolcough was the PR man for the Asiatic Petroleum Company. Each of these men directed funds towards documentaries that were designed to make either their specific funders, or the industry as a whole, look benign and even essential to societal progress.

The story these PR men loved best was that of the industry as a giver of life to a region, the sole-provider of modernity in backwaters and hinterlands. Versions of this oil company-as-moderniser narrative are recurrent in sponsored documentaries. It is particularly evident in the film Persian Story that was produced by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1951-52, in the midst of the political crisis that preceded the neo-colonial regime change instigated by the British in 1952. (The story was re-presented in Nasrin Tabatabai & Babak Afrassiabi’s exhibition ‘Seep’ at the Chisenhale Gallery in 2013 – see my review in AM366). The Persian Story tells us nothing of the political situation in Egypt at this time: instead, we see a munificent British oil industry planting wealth and happiness in an otherwise impoverished desert country. An even more saccharine version of this narrative arc is by Robert Flaherty – the most famous documentarist of them all – who made Louisiana Story, 1948, at the behest of the Standard Oil Company. The film is a docufiction – a fictional narrative set within a documentary mode – in which a young boy playing in the bayous of Louisiana with his pet raccoon witnesses the construction of an oil rig and, finally, sees the benefits it brings to the people of the region (they become rich). Other narrative arcs in oil-funded documentaries include the fetishisation of technology (Shell Spirit, 1963) and the portrait of a worker (A Day in the Life of a Coal Miner, 1910). Such films, particularly those whose makers viewed them as ‘art’, are adept at what Brian Winston has called the ‘running away from social meaning’ in early documentary films.

Sponsorship from big business, organised through PR agencies, has increasingly been a facet of art exhibitions, even – and perhaps especially – those of a formally ‘radical’ nature. For example, the tobacco company Philip Morris International both commissioned and funded ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, curated by Harald Szeemann at Kunsthalle Bern in 1969. Any claims to radicality for the exhibition are seriously undercut by this financial arrangement. In the preface of the exhibition catalogue, John A Murphy, the group’s president, drew attention to the parallels between business and ‘innovation ... without which it would be impossible for progress to be made in any segment of society’. A more knowing and deliberate union of art and industry is seen in the case of the Artist Placement Group (APG): the artist-run group that sought to reclaim territory for left-leaning artists within progressively minded companies (Features AM366). By placing a number of artists in British industry in the 1960s and 1970s, the APG invoked industry as a site of escape from the art market. A key point of contact was the oil industry: artist Andrew Dipper was placed with Esso; one of APG’s trustees was Sir Robert Adeane, who was also a board member of Shell; and one its directors was Tom Batho, who was the head of employee relations at Esso. Unlike Grierson’s propaganda model, however, APG’s intention was to avoid instrumentalisation: a key watchword for the APG was independence – the artists were financially and artistically independent from host industries. Because of APG’s financial independence from the companies it was involved with, its claims were certainly real. Its work was, in some ways, a testing of the agency of art that measured the boundaries of art’s power beyond the remit of the gallery. It may be argued, however, that the APG was only partially in control of its self-declared independence: for any sponsoring company, the value of art is its public relations functionality. Indeed, while APG artists generally did not directly contribute ‘products’ to the industry, they were to be seen as the giver of ‘intangible and unpredictable’ value to the host organisation.

Today, in situations in which art is financially dependent on a private sponsor, art’s agency clearly cedes to the controlling voice of the chief executive. In a few cases there may be ways around the situation: as the critics of BP’s involvement with Tate (including Liberate Tate, but also Tate members not affiliated to this group) point out, membership fees may actually significantly outstrip funding from BP. Furthermore, they argue, art institutions have already exercised their right to refuse sponsorship from unsavoury patrons: few galleries would today accept money from tobacco corporations, as did Szeemann when he curated ‘When Attitudes Become Form’. However, such choices are as difficult as ever to make. The art world is increasingly dependent on money from right-wing business tycoons (Michael Bloomberg, Pojo/Anita Zabludowicz, Bernard Arnault, Eli Broad, Gustavo Cisneros, Francois Pinault, to name a few). Art institutions often have very tough choices to make: to cut jobs, exhibition programmes, limit institutional growth, or to turn a blind eye and accept the money. To be free from such sponsorship means a determined refusal to accept deals with the worst offenders.

The worst position of all is the passive acceptance of sponsorship by those blind, devout believers in art for whom ethics is an impossibility and art is a value that transcends all else. This plays into the hands of the propaganda model of art that has long been pursued by corporations’ PR officers in the realm of documentary film. Do we really need art of the kind that genuflects to corporate greed? Following on from this question are others that still need to be addressed: do we need more art, or less art in the world? Is there any such thing as ‘clean’ money? Is there any form of corporate sponsorship that is, in fact, pure and munificent? However we come to answer these ancillary questions, it is clear that the social and ecological cost of the oil industry – smoothed by almost a century of the industry’s PR use of the arts – has left the world in a treacherous position.

Colin Perry is a writer and critic based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 369: September 2013.