Feature

Art Capital

Simon Ford and Anthony Davies explain the surge to merge culture with the economy

‘It was the most moving evening of my career at the Royal Academy,’ said Norman Rosenthal (Evening Standard, September 24, 1997). ‘There were 1,500 people here [at the ‘Sensation’ opening], from the greatest and the goodest to the most marginal people who get into these things: young people, the artists themselves, RAs.’

Amongst the greatest and the goodest were leaders of industry, politicians, television executives and property developers. The quote raises at least two questions. Firstly, why are the great and the good suddenly so keen to be associated with contemporary art? And secondly, what kind of ‘marginal’ role can artists expect for themselves in the rebranded new artworld order of London.

The answers to these questions will not be found in art magazines, exhibition catalogues or in the increasing number of sycophantic feature articles in weekend newspapers and lifestyle magazines. These days if you want to know what is happening in the artworld you have to look beyond the promotional blurb of the ‘on message’ hucksters to the financial and marketing media. In the 1990s London started to swing when the City told it to, when culture became strategically linked to inward investment. In the words of Colin Tweedy, the Director General of the Association for the Business Sponsorship of the Arts (ABSA), we are seeing a ‘surge to merge culture with the economy’ (Sunday Times, October 19, 1997).

Until quite recently, contemporary art in Britain had a real image problem: it just wasn’t sexy enough. Art had to get younger, more accessible, more sensational. In short, art had to become more like advertising. A few culture entrepreneurs, encouraged by business contacts, set about transforming sections of the artworld into a thriving enterprise zone. Initially the main movers behind this rebranding exercise were those members of the sponsorship industry that recognised the ptential of brand building through lifestyle marketing. Hungry artists and cash-strapped institutions were in a weakened position, unable to refuse. Soon they were begging for it.

There is a number of theories as to why business leaders should want to influence and direct culture. The most compelling is linked to global financial markets and London’s bid to consolidate its position (achieved over the last five years) as the European financial services centre. Culture is an important element of the marketing mix that sells ‘London’ – the other factors being a conveniently placed time zone that straddles the US and Japanese markets; the English language; a relaxed regulatory environment; strict employment laws (low strike rates) and EU membership. All else being equal, culture (and cuisine) provided the added value that kept London ahead of Berlin, Frankfurt or Paris. When Newsweek called London ‘the coolest city on the planet’ business leaders basked in what the Financial Times (November 27, 1997) called ‘reflected self-image’ where ‘decision-makers want to be living and working in places which reflect well on them’.

Another theory, not unconnected to the first, is that promoting national culture abroad generates higher export earnings at home and, just as importantly, attracts tourists. To become a tourist trap the modern city requires its Grands Projets, like the Tate Gallery of Modern Art at Bankside and the New Millennium Experience (NME) at Greenwich. Both projects are part of a bid to make London ‘The Millennium City’ and both carry the qualified support of London’s business leaders as represented by organisations such as London First, founded in 1992, and its inward investment subsidiary London First Centre, founded in 1994.

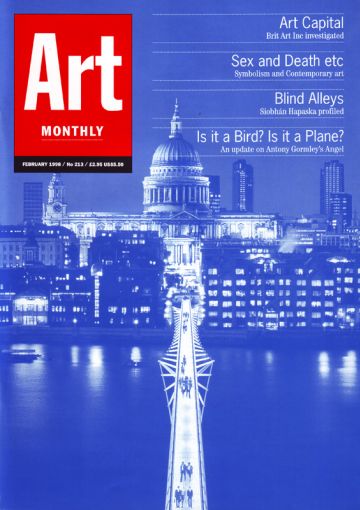

London First is one of 11 organisations that form London Pride Partnership. LPP, together with Ministers from the Cabinet sub-committee for London, recently formed the Joint London Advisory Panel in 1995. Another associate of London First is the Central London Partnership which, with the Tate Gallery, the Financial Times and Mercury Asset Management (major shareholders in Christie’s, sponsors of ‘Sensation’), helped sell the idea of a pedestrian bridge linking Bankside with the City. The Millennium Bridge – like Clement Greenberg’s metaphor of the ‘umbilical cord of gold’ that links the Avant Garde to the ruling class – will serve as a potent symbol of culture’s ever-multiplying links with capital.

The millennial celebrations also form a key part in the ‘rebranding of Britain’ strategy which began to make the headlines in May 1997 with the Design Council’s ‘New Brand for New Britain’ discussion paper. In July the English Tourist Board launched a new corporate identity. In September Demos published its Design Council funded report, Britain™: Renewing Our Identity, at the same time as the British Tourist Authority unveiled its new logo. November saw the Anglo-French Summit at Canary Wharf where design guru Terence Conran supervised fixtures and fittings. The big idea according to Peter Mandelson, Minister without Portfolio, was that the old image of ‘beefeaters, warm beer, and afternoon tea and cricket and village greens … was misleading. An enormous amount of Britain’s trade now is caught up in our creative industries’ (The Observer, November 9, 1997).

To help these industries the Government set up The Creative Industries Task Force chaired by Chris Smith. Established in July 1997, its stated aims are to provide co-ordination between the activities of different Government Departments; to boost the generation of wealth and employment in the creative industries and to increase creative activity and excellence in the UK. In addition to government representatives such as Mandelson, ‘great and good’ members include Richard Branson of Virgin, Alan McGee of Creation records, fashion designer Paul Smith and Eric Salama of advertising giants WPP.

Unsurprisingly there were no representatives on The Creative Industries Task Force from the contemporary art world such as the Arts Council. Such an exclusion can only be taken as a sign of the Government’s belief in the irrelevance of contemporary art to the creative industries and, in particular, its depreciation of the Arts Council of England. Mark Fisher, the Arts Minister, recently told the Financial Times (October 11/12, 1997): ‘We want to make bodies like the Arts Council more strategic and less concerned with petty detail’. With a reduced role as an advisory body, direct control of fund allocation would pass over to the Ministry of Culture, Media and Sport, thus cutting down on administrative costs and doing away with the largely mythical arms-length principle of government intervention in cultural policy. With a clear Government agenda to support the most popular and profitable parts of the creative industries the Arts Council is clearly seen as an outmoded hindrance to modernisation.

It is unlikely, though, that Government policy will lead to full privatisation. Business sponsorship despite major increases in the last 20 years, according to a 1996 Policy Studies Institute report Culture as commodity?, made up only 4% of total support for the arts in the year 1993/94. It should not be surprising then that some of the strongest arguments for continued public subsidy come from the business community itself. Groups such as ABSA’s Creative Forum for Culture and the Economy provide networking opportunities for business and arts professionals to discuss and lobby on just such matters. It also runs a Placement Scheme and Board Bank, ‘dating agencies’ where middle and senior managers are matched with the boards of arts organisations. ABSA also manages the Pairing Scheme, a Government initiative where sponsorship money can be matched pound for pound.

Although ABSA’s latest survey for 1995/96 estimated that sponsorship was slightly down on the previous year’s record high, the signs this year are for a return to rising levels of sponsorship. The picture, though, is clouded by a shift away from traditional sponsorship projects towards a more hands-on relationship with culture. The most obvious example of this has been the recent explosion of art exhibitions taking place in shops. The thinking behind this strategy can also be traced to developments in marketing theory.

The contemporary visual arts (after its successful rebranding) can now be relied upon to deliver particular audiences; broadly speaking the social categories AB and C1, and more specifically, the design and style-conscious young opinion formers. The problem for businesses trying to reach these influential but marketing-literate categories of consumers is that they do not respond favourably to conventional advertising and marketing techniques. What the marketing people advise is to associate brands with particular lifestyles. The fashionable image of the yBa promoted in magazines such as Elle, Vogue and Dazed and Confused fits the bill perfectly. Shops that jumped on the credibility bandwagon included Egg, Monsoon, Squire, Jigsaw, Habitat, Selfridges, Paul Smith, Harvey Nichols and Whiteleys Shopping Centre.

Media exposure is the most important factor in art’s much touted new accessibility. With star artists taking on the role of media personalities, debates about contemporary art work on a nuts ’n’ sluts talk-show level, and are dominated by human interest values (eg the artist as victim, the artist as rags to riches success story, the artist as rebel, the artist as pop star). The art sells the artist, and its price is directly connected to the added value associated with the artist’s media profile. This is because consumers value shared cultural experience and are willing to pay extra to commune with celebrities.

Post-Diana artist Martin Maloney, in Guardian Weekend (September 27, 1997), has a theory for this new popularity: ‘Artists are working in a way which is softer and more romantic now. They are in tune with the public, which believes in feeling and emotion.’ He then goes on to promote Habitat, in particular, as having ‘tuned in with the move towards making things easy on the eye, more concerned with the everyday’. What the article did not mention was that since August 1996 Habitat and Guardian Media Group plc have run a joint customer database for marketing purposes. This database is partly made up of names collected through subscriptions to Habitat’s Art Broadsheet (edited by Carl ‘Minky Manky’ Freedman and Ben Weaver) and its invitation lists to in-store exhibitions. In the Financial Times (November 17, 1997) this strategy is called ‘relationship marketing’ where customers trade information about their income and lifestyle in return for special offers and ‘loyalty cards’. With repeat business accounting, on average, for 90% of company profits, this form of marketing is based on the belief that ‘marketers must take steps to “own their customers” to survive in an increasingly competitive environment’.

Artists, in order to take advantage of these new cross-promotional opportunities, are finding it necessary to redefine and diversify their practice. They sell services to a variety of clients outside the ‘mainstream’ gallery system – from advertising companies and property developers to restauranteurs and interior designers. As John Warwicker of Tomato recently told the Guardian (October 27, 1997), large companies and rich backers ‘buy into people they see as working on the cutting edge of that culture because they need to be seen as part of that culture’. But to what extent are artists in control of this process? Poorly prepared in matters of business, the artist’s desperation for any type of exposure is often exploited. Is it, then, really the case that artists – as David Barrett asserted in AM211 – ‘embrace the market in a thoroughly professional way’?

Most artists have a long way to go before they can claim professional status. Apart from the few stars that the art market’s ‘winner takes all’ economy can sustain, most artists either practice other professions, have a private income or rely on State benefits. Much art activity is run on a voluntary basis with little consideration for contracts, rates of pay or conditions of service. Strictly speaking most artists are just about on a par with skilled manual labourers rather than associate professionals. With the surge to merge in full swing, and the shift to a service-based culture industry, a new type of ‘artist’ will emerge who claims professional status as a ‘broker’; a mediator rather than a producer.

Simon Ford is a librarian at the National Art Library Victoria and Albert Museum.

Anthony Davies is an artist.

First published in Art Monthly 213: February 1998.