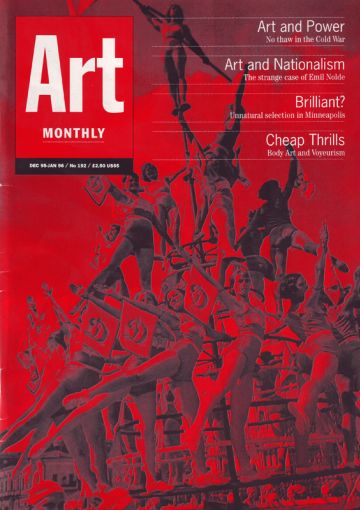

Feature

Art and Power

Julian Stallabrass finds that the Cold War still dictates the agenda in the Hayward Gallery’s Council of Europe exhibition

The pairing of spotlit sculpture that immediately greets the viewer on stepping into the darkened first room of ‘Art and Power’ can stand for the argument of the whole exhibition. Both works are displayed on high plinths as befits their monumental status: on the left (the organisers are literal), Vera Mukhina’s Industrial Worker and Collective Farm Girl, 1935, in which the two figures, holding hammer and sickle aloft, stride forward into the future; on the right, a Nazi eagle clutching a swastika in its daws. Mukhina’s sculpture is a maquette for the massive steel construction shown in Paris at the International Exhibition in 1937, and later erected in Moscow. The scale of the larger work, the size of a block of flats, has an impact that the little bronze cannot, as anyone can testify who has seen its gleaming steel panels towering above them into Moscow’s night sky. There, this monument seems to take on a meaning which is not exhausted by its compliance with Stalin’s regime for on this scale the figures draw about them the struggles and even the defeats of socialist aspirations. The dark eagle, on the other hand, is no more than a martial symbol, and at some point someone has had the good sense to put a large hole through it. But forget the differences, this exhibition implies, here are those hateful symbols, suspended side-by-side in darkness, let us remember what these totalitarian regimes had in common.

‘Art and Power’ places together Soviet, Italian, German and Spanish art of the 1930s, and beyond, by focusing first on the display of ideological art at the Paris exhibition, and then on the capitals of Rome, Moscow and Berlin under the dictators. Except under the aegis of the concept of ‘totalitarianism’, it is indefensible to group these ideologies together: they were, after all, mortally opposed. Totalitarian governments seek to bring every aspect of society under their control, the theory goes, and brook no opposition. The concept was of course invented and propagated in the Cold War and then had much to recommend it: in the 1980s, for instance, all the dictatorships of Latin America could be surveyed using this optic and only one (Cuba) be found worthy of condemnation. The Cold War has for the time being ended but with the triumph of neo-liberalism, which still finds it necessary to back dictatorships, the concept will not go away.

To comprehend fascism, one has to understand how it sprang from a widespread intellectual and political culture of right-wing authoritarianism, like a weed from manure; how it was fostered by liberal-imperial states terrified of communism; and indeed how it continues to grow in the same way. Then it comes as no surprise to find that not all fascist states are totalitarian. The way ‘Art and Power’ treats Franco’s Spain is particularly significant, for it is present almost entirely through its displays at the Paris exhibition, and by implication through the many exhibits of the Republican resistance. The little section of fascist posters and the designs for the victory monument in ‘The Valley of the Fallen’ near El Escorial give little indication of the nature of the Franco dictatorship. Its purpose was not to remake the nation by mobilising the masses, radically modernising the economy, reforging art and throwing up grand architecture, but to restore the archaic, Catholic status quo. Only one dictator, Stalin, survived the war, says David Elliott in one of his catalogue essays, and this is a significant slip: victorious and enduring Francoism, a counter-argument, is simply forgotten.

In an act of obscure revenge, it is conventional for liberals to apply vulgar Marxist principles only to the art of totalitarian states. Look at these bombastic monuments, this poor, realist painting and these inflated urban projects, we are told, and you hold in your hand the very ideological heart of these regimes. Every excess column and each overly sharp muscle is a clue to their degeneracy. Yet so much seen here is no more than anodyne, and viewers must actively read tragedy into paintings of building sites, nudes and portraits of professional men. The most effective work in painting and photography, certainly from the Soviet and German camps, is missing. Perhaps it is still too controversial to show. The result tells us little about the specific character of each regime, not least because it is largely their view of utopia that is shown, rarely works detailing what, from their perspective, was wrong with the world. Oppositional art is almost entirely confined to avant-garde objections to fascism and communism. What was Nazism directed against? You would never know from this exhibition where it seems only to recommend health and efficiency.

You could read the art of any state in this way. It would be easy to make a selection of works from, say, the National Portrait Gallery, or take architectural drawings of Britain’s own monumental classical-modernist buildings (such as Senate House) or run videos of royal parades, and slip them without any real disturbance into this show. Similarly, much is made of the demise of the Avant Garde in Germany and the Soviet Union, yet their position was hardly secure elsewhere: in Britain, it was virtually wiped out in the 1920s by sustained conservative opposition.

With neo-liberal orthodoxy reigning globally, the economic alternative banished, the system becomes transparent, lost from sight, when there is no longer anything which by contrast lends it colour. And its venerable predecessor, the liberal and imperial state, is certainly invisible in ‘Art and Power’. These were the regimes which for so long supported fascism (they were particularly enthusiastic about Mussolini), betrayed democracy in Spain, whose main concern was to protect their global empires and hope that Hitler would turn his armies eastwards rather than westwards, as indeed he always said he would. Without this missing link, the two ‘totalitarianisms’ face each other, as they did across the grounds of the Paris exhibition, like two dinosaurs, their rise and their extinction equally shrouded in darkness.

Without it, too, it is hard to imagine why these monsters ever fought each other, and here is another vital dimension barely present in a show which purports to cover the period to 1945. One room, the last, is devoted to ‘Nemesis’, a generalised and largely avant-garde lamentation of the cost of the war, and there is also some suggestion of war at the very end of the Moscow section, induding Mukhina’s fine head of a Female Partisan, 1942. But where otherwise are the official responses of the powers which fought? Where the extraordinary photographs of Arkady Chajhet and many others attached to the Soviet army? To indude such work, though, would be to muddy the clear blue waters and so, like many conservative accounts of these times, events after 1941 are highly abbreviated.

Why show ‘Art and Power’ now? When the Wall first came down and communism in Europe collapsed, it seemed for a time that Socialist Realism was safe to look at and, as if in reaction, fascist motifs started to appear insistently in advertising. The apparently lifeless forms of socialism and fascism could be displayed to remind inhabitants of the capitalist states of their good fortune – this is, after all, a Council of Europe exhibition. Yet, although neo-liberal orthodoxy still seems secure, these are less certain times and the organisers have pulled their punches. The uncertainty is signalled in the catalogue, especially in the concluding passages of its introductory texts: Eric Hobsbawm says of these regimes and their theatrical displays that ‘The curtain is down and will not be raised again’. By contrast, the organisers think that ‘The spectres of authoritarianism, racism and rampant nationalism which haunted these years are still with us today’. So the bacillus of totalitarian art is encased, stripped of its most virulent strains, in the South Bank’s bunker, acting as inoculation, not infection.

In housing together, and in the first room side-by-side, the arch-enemies of the 20th century, and in its blindness to the guilt of liberalism and capitalism in the unfolding tragedy (where would Hitler have been without the Depression?), this exhibition is a disgrace. Without the sacrifice of communists in many countries – in Germany where, pressed into forced labour, they sabotaged the V rockets aimed at London; in partisan and resistance movements in Greece, France, Italy and Yugoslavia but above all in the Soviet Union where many millions of people gave their lives to break the German war machine, European fascism might still be with us. If this exhibition demonstrates one thing with absolute clarity, it is the callous disregard of what E P Thompson called ‘the condescension of posterity’.

And this raises a final question: in the contemporary art world we are much used to irony and cool distance so that most of the work shown here was bound to look dated and overblown, ridiculous even – and there were people who found things they could laugh at in this mausoleum of an exhibition. This is bound to be the case as long as art is only something we stumble over on the way to the bar, as one reviewer recently put it in these pages. But are there not causes, and were there not events, which this art, if anything, underplays? Think of the 25 million Soviet dead and suddenly Mukhina’s gigantic monument seems vanishingly small.

Julian Stallabrass is a London-based critic and art historian.

First published in Art Monthly 192: Dec-Jan 95-96.