Feature

Art and Dyschronia

Bob Dickinson on art that challenges populist governments’ rewriting of the past

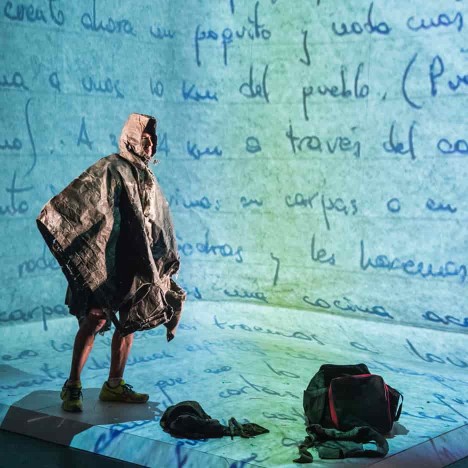

Lola Arias, Minefield, 2016

Bob Dickinson warns that our concern for the future, not least of the planet, should not distract us from what is happening to the past at the hands of right-wing populist governments intent on rewriting history.

If, as the neuroscientist Russell Foster suggests, human beings now face a choice between manipulating time to offer either ‘time paradise or “Uchronia” for a time-stressed populace’ or the ‘time hell of “Dyschronia”’, it seems that we are opting for the latter, in more ways than one. Yet it is not just a question of the way work and globalisation threaten the natural rhythms governing sleep, wakefulness and mental stability, as art critic Jonathan Crary argued in his polemic 24/7; it might also be argued that one key aspect of time – the past – has undergone a crisis that continues to be reflected in art.

So far, artists have made much of the temporal confusion that Foster described in his 2004 book Rhythms of Life (co-authored with biochemist Leon Kreitzman), beginning with the move from biological time, marked by our circadian rhythms, to the imposed forms of mechanical time that enabled the industrial revolution to take place. For artists, that change led to the development of new techniques that could capture time, such as photography, film and audio recording. The appearance of time-based media in the visual arts and music during the 1960s enabled artists like Bruce Nauman to use video to slow down and open up time as a field for investigation. Since then, digital technology has provided opportunities for 24-hour social interactions worldwide while work becomes ever more precarious and short-term. Not for nothing has the term ‘zero hours’ become applied to contractual relations with employers. Now, as the climate emergency becomes increasingly evident, there is an urgent need to come to terms with geological deep time (see Rob La Frenais’s ‘Deep Time’ in AM422 and Sophie J Williamson’s ‘Underlands’ in AM445), which many artists are trying to address in relation to the much-discussed idea of an Anthropocene era (see my ‘Art and the Anthropocene’ in AM389).

However, in an era of growing right-wing populist politics in the UK and elsewhere, and specifically of government-declared culture wars, a new aspect to this dyschronia has begun to emerge and it concerns the increasing politicisation of history. It is clear that, for some political leaders, history is simple and sacred, particularly those embracing reactionary forms of nationalism for whom there is little distinction between history and myth. Complexity, and especially issues of, for instance, guilt, do not enter the storyline. In this context, it is interesting to look at the work of some contemporary artists who seek to situate their work in a close and direct relationship to history in an effort to expose that buried complexity.

The Berlin-based duo Prinz Gholam, for instance, frequently choose to make performances in the presence of pre-existing artworks, both contemporary and historical, in spaces that vary from galleries and museums to important archaeological sites. With their origins in different cultures – Wolfgang Prinz is German and Michel Gholam is Lebanese – their work emerges from a multi-layered and highly researched set of cultural and historical dialogues. My Sweet Country, 2017, for instance, took place at the Agora of Athens, the ancient city’s equivalent to a marketplace and location for public gatherings, which also possesses political and religious significance. The Agora is a site that may have first been conceived as long ago as 10,000bce. Conscious of the many historical interpretations this monument has accumulated, the artists reflected, too, on paintings by Eugène Delacroix that commented on the early 19th-century Greek war of independence from Ottoman rule, as well as writings about Delacroix by the 20th-century French critic and novelist Michel Butor. Importantly, consideration was also given to the idealised images of Greek monuments photographed by Elli Seraidari, aka ‘Nelly’, using posed female models during the period of the ultra-right-wing Metaxas Regime of the 1930s. Prinz Gholam’s physical approach, incorporating poses derived from these historical texts and images, exposed a complex series of interlinked interpretations. In this case, it also enabled Prinz Gholam to investigate the origin of more than one modern nationalist movement buried under the traces of another.

Prinz Gholam’s most recent work has undergone the addition of simple, hand-drawn paper face coverings. These appeared in My Heart is a Poised Cithara, 2020– 21, which saw the cithara (an ancient type of lyre and an ancestor of the guitar) being played as well as posed in among the ancient contents of Rome’s Palazzo Altemps, a 16th-century Papal building that houses a significant collection of classical statues. But the masks the duo were wearing made it impossible to tell who was playing the cithara and who was holding or wearing a decorated piece of drapery mimicking the realistically carved robes that dressed the subjects of the statues. In addition, the rooms, as well as the much older artworks they contain, all combined to have an impact on the human performers, an effect the artists have drawn attention to in remarks they have made about the importance of scale in their work. It is striking that the statues are larger than life in the metaphorical as well as the literal sense, an impression which has been made almost theatrically apparent by the shape and size of the rooms. Prinz Gholam, conversely move slowly – seemingly uncertain but always showing great tenderness, their masks as if a form of naive camouflage – through the gargantuan spaces.

Prinz Gholam’s recent use of paper masks accentuates the theme of layering. But because of the pandemic, the necessary (and in the UK inconsistent) wearing of face-coverings only makes more mysterious the older, ceremonial or theatrical uses of the mask. Another recent work, While Being Other, 2021, took place at the Mattatoio, a former slaughterhouse, also in Rome. The artists covered the building’s 19th-century interior walls with large-scale drawings in coloured pencil on paper, from the top of which rows of hand-decorated paper masks stared down. At floor-level, installations of found stones invited comparison with human physiognomies. Here, then, was a collection of invented faces and psychologically projected faces, all this invention and projection also amounting to further forms of layering, though all the faces remained anonymous. Within the context of the building, and at that particular moment of the pandemic, the work pointed also towards the containment of death as a central aspect of collective, urbanised history.

The homemade and non-naturalistic nature of Prinz Gholam’s masks shares certain similarities with those used by Chilean-American experimental filmmaker Niles Atallah, who is also concerned with history. Rey (King), 2017, is the fantastical but factual tale of the French adventurer Orélie-Antoine de Tounens, who, in 1860, travelled to Chile and declared himself king of Patagonia and Araucania, the tribal territory of the indigenous Mapuche people. Tounens was arrested by the Chilean authorities, who accused him of spying for France; he was put on trial but declared insane and subsequently expelled, only to return three more times in the early 1870s when he again experienced total failure before dying in poverty back in France. Whereas Prinz Gholam scribble abstract patterns on their face-coverings, Atallah employed papier-mâché masks that crudely simplified the character being played when performing their designated role: that of a judge or king, for instance, or a soldier – or even a horse. Echoing the ancient ceremonial use of masks made by the Mapuche themselves, the use of masks in Rey accentuates the extent to which the characters are compelled not only to transform themselves but also to victimise each other, so that some masks appear to be damaged. The film also includes footage which Atallah degraded by burying it in the ground for long periods, or by scratching it by hand, as well as archival footage from the early 1900s, which lend the whole film the quality of a distressed historical artefact-cum-nightmare. All in all, the film mocks the delusional side of colonialism by triggering a dyschronic release of tall tales, legends, lost hopes and mysteries.

The way that Prinz Gholam or Atalla have chosen to work results in richly layered histories emphasising the repeated covering over of more than one troubled past. The removal of these layers to expose repressed aspects of history can sometimes cause shock, as was the case in the event that launched Beca, the radical Welsh art movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Taking its name from the Rebecca Rioters of the 1830s and 1840s (some of whom destroyed toll gates in West Wales in protest against English taxes on rural communities), Beca’s activities began with Paul Davies’s performance WN, 1977. This took the form of an intervention at the annual Eisteddfod which that year took place in Wrexham, directly outside the Welsh Arts Council’s international art pavilion, to which no Welsh artists were invited. Without prior warning or previous arrangement, Davies lifted a railway sleeper, into which he had cut the letters WN, above his head and held it there. Many eyewitnesses reacted with bemusement or consternation because the initials, standing for Welsh Not, were a stark reminder of the days, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when the Welsh language was illegal and schoolchildren overheard speaking it in class were made to wear a wooden board marked WN around their necks – another form of layering. What was for schoolchildren a punishment spelling out cultural hegemony became for Davies, as he stood there, a burden. A photograph of Davies in action shows the Italian arte povera artist Mario Merz standing directly in front of him and speaking – perhaps supportively – shortly before the Italian artist is said to have taken the Welsh Not sleeper when Davies could no longer support it himself. The Welsh Not sleeper’s subsequent history exposed further layers: Davies carved it into a giant Welsh love spoon, complete with traditional, complex knot decoration, thus punning ‘knot’ with ‘not’.

Despite Davies’s early death from heart failure, the work produced by the Beca group subsequently and powerfully combined the use of collage and found objects to illustrate colonial domination and superimposition in works such as (Paul’s brother) Peter Davies’s Ty Haf/Summer House, 1984, in which the photograph of a holiday cottage erupts in a blaze of hot yellow and red paint, containing a smoking black heart, all dwarfing a printed union flag still flying from a tiny pole planted in the lurid, lime green lawn. Other, younger artists, like Tim Davies, also influenced by Beca, continue to explicate historical themes and to work out their impact on Wales. His work Capel Celyn, 1997, commemorates the village which in 1965 was deliberately flooded by Act of (UK) Parliament to become Bala Reservoir, which was to supply water for Liverpool. The work is based on one nail that Davies recovered from the area and which he then cast in wax to make 5,000 replicas, which are arranged as a floor-level installation. It showed that simple historical evidence can be rescued from the mud to make a submerged history visibly and hauntingly poetic.

A comparable technique for exposing the hidden or repressed layers of history is explored by the Buenos Aires-based writer and director Lola Arias, who uses personal archives of handwritten notes and photos then projects them onto screens as well as onto the bodies of non-professional performers. In biodrama productions like Minefield, 2016, performed by ex-members of the armed forces in both sides that fought in the Falklands/Malvinas conflict, or Atlas of Communism, 2016, performed by women who grew up in East Germany, the technique immerses them in images and words from their past, while they re-enact events in which they actually took part. Past and present are often deliberately brought together with surprising results. One performer in Minefield was a sailor on board the Argentine battleship the Belgrano when it was torpedoed, and long after surviving the ordeal he became the drummer in a Beatles tribute band. Recreating the terrifying moments when the ship sank, he plays a drum solo while the rest of the cast, playing other desperate survivors, try to ‘swim’ towards the drum kit, which represents a rescue dinghy. What this work and Atlas of Communism deal with at a deeper level, however, is the trauma of survival: what happens when people caught up in events have to endure change and somehow survive afterwards, with the memory of shock buried deeply inside each individual.

It may also be instructive to remind conservative populist politicians and media outlets that history is not confined to the past. Paradoxically, history can open up vast tracts of time stretching into the future, too, as the Berlin-based artist Susanne Kriemann has shown in her long-term project Pechblende (Pitchblende), which she began in 2014. The work focuses on the mountainous Ore region in the south of the former German Democratic Republic, where uranium was first discovered in the 18th century and where between 1946 and 1989 the radioactive substance uraninite, formerly known as pitchblende, was mined under gruelling conditions for use in Soviet nuclear warheads. The area has since been transformed by landscaping, and seems timelessly safe, but in fact it remains severely polluted by radiation which, it is thought, will not decay for another 100,000 years. Kriemann began by making ‘autoradiographs’, images resembling X-rays that were made on photographic paper by radioactive objects retrieved from the area, including a miner’s helmet, a water bottle, a rubber boot, plus one or two living samples, including a frog. More found objects and archives were brought together under the title Volume, 2016, for which Kriemann collected three types of wild plant from abandoned mines at Gessenweisse and Kanigsberg: false chamomile, wild carrot and ox tongue. These three plants had been identified as being the most efficient at absorbing the heavy metals and radioactive chemicals which are now used in the manufacture of mobile phones. Once dried, the plants gave their names to the resulting series of photographs, Falsche Kamille, Wilde Möhre, Bitterkraut, 2016, based on images captured on the artist’s mobile phone and printed with ink made from the pulped remains of the plants. It is an example of an artwork that proves that whether we are dealing with history or radioactivity, what goes around comes around. To realise that this abundant landscape has only been recently established, and, furthermore, destined to stay invisibly poisonous for millennia, is just another mind-boggling symptom of dyschronia.

Bob Dickinson is a writer based in Manchester.

First published in Art Monthly 452: Dec-Jan 21-22.