Feature

Art & Activism

Gavin Grindon reports on the crisis in Copenhagen

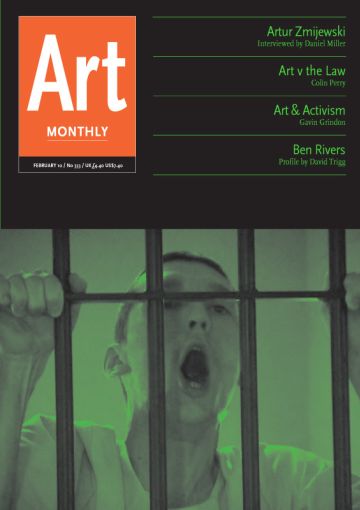

Bike Bloc

The rhetoric surrounding the COP15 climate change summit in Copenhagen set up the city itself as a space of hope, crisis and opportunity. Between politicians, lobbyists, NGOs and activists, ‘Copenhagen’ became a byword for a decisive, city-wide public sphere to confront the challenges posed by climate change. Although there were many competing voices from developing nations and civil society, the main economic model proposed to avert the crisis was that of carbon trading – financialisation which sought to overcome the internal limits of a market by turning a crisis in its expansion (pollution, unpaid debt) into a meta-market of derivatives (carbon credits, debt trading).

Privatising the air we breathe – or rather its future – this economic model attempts to imagine and shape our future social relations. In other words, it attempts to enclose, for private profit, the public space of dreams, promises, hopes and desires. Politics entered here upon the terrain of aesthetics and it was unsurprising that, during the two weeks of the summit, the public effervescence around it extended far beyond explicitly political institutions and ultimately reached deep into the city’s cultural life. Copenhagen’s cultural institutions attempted to engage directly with the democratic process, as a number of visual and artistic projects explicitly stated their intention to also engage – and build – a public sphere around the issue of climate change. But as they did so, they revealed another crisis in contemporary art’s ability to engage with issues of social change.

Institutions, from NGOs to corporations, had been quick to turn to art for the same ends. The former were the most bluntly propagandist. The WWF opted for two melting ice sculptures of polar bears. Oxfam did the same, adding a performance with a native of the Maldives suspended up to his neck in dirty water. Greenpeace, meanwhile, installed a photography exhibition on the effects of climate change at the Bella Centre. The most visible project, however, was the inescapable and cringingly titled ‘Hopenhagen’. This project was located in City Hall Square in the centre of Copenhagen, and produced using a combination of private commercial and public city finance which pulled together corporate practices of ambient advertising and public art. Huge advertising hoardings from Siemens and Coca-Cola offered ‘a bottle of hope’, while a series of clear glass ‘cabins’ lit with green neon strips hosted sundry exhibitions: showcases for, variously, new green technologies, unrelated commercial products and public art projects. This corporate impulse to capitalise on the swell of public enthusiasm about climate change was no different for the marketing departments of the city’s galleries, which similarly sought to feed on public feeling with a series of themed shows. The exhibition ‘RETHINK: Contemporary Art and Climate Change’, was staged across four spaces, whose titles, such as ‘Rethink Relations and Rethink Kakatopia’, specifically sought to engage the public sphere.

Staged in Gallery Nikolaj, a church converted internally into a white cube, the sense of quiet contemplation of ‘Rethink Kakatopia’ was twofold. This was in great contrast to the archetypal emphasis on open-air city crowds, noise, urgency and bright light of ‘Hopenhagen’. The exhibitions were marked by a lack of urgency and contemporary context compared with the more results-driven initiatives of governments, NGOs and corporations. Rather than offering critical distance, the institutional arts’ response appeared less relevant. Perhaps this was partly due to this different institutional frame, but ‘Hopenhagen’ was also unafraid of at least appearing to make direct comment and intervention. By contrast, the affects presented by the art institutions were more commonly not those of hope, but of passivity and despair. The curatorial statements were conspicuous by their tentativeness: ‘The artists do not offer actual solutions to these problems – but they present us with images that may serve as tools for reflection, debate, awareness – and possibly action.’

Like the corporate interventions, the ‘RETHINK’ gallery programmes fed on public enthusiasm for social change, yet withdrew in apparent horror at the prospect of actually effecting, or even discussing any. The works selected provided little in the way of social context. Bill Burns contributed an amusing series of tiny examples of safety clothing for animals, while the Iceland Love Corporation presented a video of three women in full makeup and fur coats obliviously enjoying fine consumer goods in an icy wasteland. As a debate on climate change, the terms these works set were nebulous and ahistorical. The works concerned themselves with the theme of crisis and contradiction, but in a situation where the world’s biggest industrial project and largest capital investment, Canada’s tar sands, is culturally all but invisible, they embodied this crisis twice over. If the NGO-sanctioned art exhibited a clumsy specificity, then the level of disengagement here was no less vulgar for being at the opposite end of the spectrum.

The public sphere in Copenhagen seemed as eviscerated of content as that of the corporate space, where Coca-Cola and Siemens encouraged you to ‘become a citizen’ by checking out their websites. This tells us something not just about art institutions but about the state of the public sphere in an age where the common spaces upon which it was founded have been systematically eroded by capitalist enclosure and privatisation. Instead, the art which most successfully engaged with the issues of climate change was that which had more affinity with extra-institutional activist practices.

In recent years, ‘activist art’ has become very fashionable. The term is a broad one and has been deployed to cover a wide range of art practices, from ideologically critical practices within institutional art forms, to community-orientated art projects, to playful street art, to extra-institutional practices of invisible theatre and tactical media within social movements. However, much art that is socially critical, engaged or activist, is only so within invisible but strict, institutionally defined limits. Such art might mimic the practices or raise the issues of activism, but it does so in a context without consequence. One can be as subversive and questioning of social relations as one wishes in a gallery. In fact, it is actively encouraged: often rewarded with good reviews and funding. But doing so within actual social relations has greater risks, which many artists and institutions are less willing to take. Much that is labelled art activism is not, in fact, particularly active when it comes to changing society. In Copenhagen, both Gallery Nicolaj and Freie Internationale Tankstelle pulled out of hosting the Bike Bloc art-activist project when it became clear that the project was not a hypothetical fantasy bound to the gallery but would actually be carried out in the streets, with all the risks of real social activism. Instead, Bike Bloc found a home in the Candy Factory, one of the city’s several activist social centres.

There is a curious dynamic here. At the same time that ‘activism’ is being received with unprecedented enthusiasm by liberal art institutions, it is being criminalised and excluded as ‘terrorist’ by political establishments. In the UK, organisations such as the sinisterly named National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit have turned their attention to non-violent climate activists, and new anti-terrorist police powers are now regularly used to discipline and interfere with social movements. The US, too, has seen a phenomenon which has come to be called the Green Scare: the legal and legislative extension of the definition of ‘terrorism’ to encompass non-violent civil disobedience for ecological causes, under the banner of the invented term ‘ecoterrorist’. In Copenhagen, media scaremongering about an invasion of foreign activists was accompanied by a hasty blanket extension of police powers to include ‘pre-emptive’ mass arrests of hundreds of people at a time.

The vampiric dual movement of art institutions – simultaneously towards the inclusion of the energy and critical innovations of social movements, and yet away from the real political body of their practices – leads to the kind of dead representation of social engagement on show at Gallery Nicolaj. This might sound like a melancholy analysis, but perhaps the incorporation of social struggle into art could lead not to the disappearance of that struggle into recuperation, but to its viral proliferation across the field of artistic production. In the most positive reading, the art market’s capitalist enclosure of these practices is only to disseminate them further. This model of deferring social conflict to a higher plane of abstraction is the very model of prolonging its own life that capital takes towards social struggle elsewhere. So we might look again – differently – at the art market’s attempted enclosure of activist practices. Contemporary art might conjure up the spirits of the social movements in a borrowed language which is often an empty farce, but the ironic misuse of borrowed language is also the means of heresy: the very practice of turning the discourse of an institution upside down to present new values and forms in the language of the old, and introduce rupture in the guise of continuity. So where does this leave us? This simultaneous inclusion and exclusion puts would-be art activists in the position of a kind of revived institutional critique. The possibilities for such an impossible, enclosed practice can range from a troubling but powerless irony, such as that of Santiago Sierra, to the vital exodus of an art that actually remakes social relations, and in so doing can build its own social institutions.

By far the most interesting art practices in Copenhagen were those that engaged with this situation, and took as their practice the constitution of a critical counterpublic sphere. Institutionally, such practices have tended not to have official support but have instead been founded in the creativity of autonomous social movements. However, a few such practices in Copenhagen were notable for their movement across official institutions, moving on the margins to play the recuperation of ‘activism’ by the art world against its exclusion by the state.

One such example was the project New Life Copenhagen (NLC) organised by Wooloo.org. In response to media scaremongering about the invasion of dangerous foreign activists, NLC connected over 3,000 activists with locals of the city willing to let them stay in their homes. The new ways of living together that this initiative attempted to produce were assisted by host/guest books which provided a range of questions for discussion. The project was part of ‘Hopenhagen’ and shared its funding, but, from this initial position, NLC began to develop new social counter-relations which directly contested the economic interests of its host institution. A position both within and against is one fraught with contradictions and NLC can be found described online variously as art, activism, community building and rebranding. Yet such practices make the most of those contradictions and sacrifice ideology for action. Though one might critique the project for lending ethical legitimacy to its backers, NLC nevertheless directly facilitated the work of activists across the board. Perhaps in response to such objections, more conventional practices of critique were also present. NLC was showcased in one of the boxes in ‘Hopenhagen’ but, once inside, visitors were invited to be videotaped taking a pledge to never drink Coca-Cola again in response to the company’s alleged practices of greenwashing and crimes against developing nations.

Meanwhile, the independent Gallery Poulsen invited the Yes Men and, interestingly, the NGO Avaaz.org to work from its space. Avaaz worked with performers who developed an awkward kind of ‘performance lobbying’ which placed the theatrics of protest inside the official conference, with aliens mixing among delegates, demanding to be taken to their climate leader. The Yes Men worked with a local collective to produce a reproduction of the Bella Centre’s briefing room in the gallery, and issued a video press release on behalf of the Canadian government (which had blocked any negotiation on emissions) announcing a reversal of policy and a willingness to curb emissions. A spokesperson for the prime minister of Canada attacked an innocent Canadian reporter for the hoax while the US energy secretary refused to pose with the prime minister for photos. Canada’s minister for the environment was forced to issue an absurdly bombastic rebuttal, attacking the Yes Men for the cruelty and immorality of infusing people with false hope.

However, without a doubt the most ambitious and radical of the activist art projects was Bike Bloc. Working initially out of the Arnolfini gallery in Bristol as part of ‘C Words’, a brave exhibition of activist art projects, Bike Bloc brought together bike mechanics, artists and activists to collectively design and build a new practice of civil disobedience to facilitate the protests on 16 December using Copenhagen’s most recyclable resource: discarded bicycles.

Though the problem of Bike Bloc, a project by the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination and the UK’s Camp for Climate Action, was something like a renewed Constructivism – producing art as part of, and using the means of, a radical movement remaking society – its aesthetics were pure Surrealism. Fish-bikes, tall bikes, long bikes and a series of more practical activist-bike modifications, as well as a troupe of tall bikes with heavy-duty carrying platforms welded between them, were collectively designed, produced and wheeled out of the Candy Factory over a week. On the day, Bike Bloc brought new creative practices to the direct action of social movements. After training activists to work together in small groups on bikes as part of an overall ‘swarm’, the bikes outmanoeuvred police vans and horses in a series of exciting getaways, sneaked an inflatable bridge to the moat around the Bella Centre, and were recomposed as slow road blocks or outright barricades to interrupt police repression of the day of action – at one point blocking two lanes of motorway north of the Bella Centre. One part of the swarm was ‘sound bikes’, with high, directional speakers welded to them, which played ambient, multiple-channel compositions through the crowd, appropriate to the situation. One part of the crowd, which was being pushed by police trying to enclose and move it on, suddenly began emitting disparate recordings of braying and mooing, while wild animal calls and disruptive shrill drones were directed towards riot police trying to organise a charge. Overall, Bike Bloc assisted the aim of the day of action: to enter the grounds of the Bella Centre and set up an alternative, critical, people’s summit in co-operation with the 200 delegates who left the centre to join the activists outside. Though its methods were more militant, the aim was once again the constitution of a counter public sphere of genuine democracy.

Art can move between the gaps. These practices all functioned, in different ways, to reverse-engineer social institutions, connecting their access to space and funding to the creative and critical resources of extra-institutional activist practices. Though some of these art-activist practices gave the lie to much of what is vaunted as ‘activist’ in the art world, by actually being sited within social movements, it is also worth noting – and commending – the risk taken by institutions which have supported genuinely activist practices. With the changing climate at our backs, this is no time for cowardice. The two sides of this crisis met outside the Bella Centre: one employing the creative vitality of practices drawn from art and activist social movements, the other employing practices drawn from technologies of discipline and social management. At the time of writing, some of those at the people’s summit are still in jail, for shouting ‘push!’ to encourage the crowd. This new institutional critique – or, rather, counter-institutionalisation – as a militant exodus from enclosure, presents a new field of creative political possibilities, a new trajectory for hopes, dreams and desires to build new social institutions. That this heresy will take the form of an absolute limit to capitalist enclosure is just such a hope.

Gavin Grindon is a research fellow in the Visual and Material Culture Research Centre at Kingston University, where he is writing a history of art and activism in the 20th century.

First published in Art Monthly 333: February 2010.