Report

American Fallacy

Chris Townsend reports from Texas on the Myth of the West at a time when California is beset by wildfires

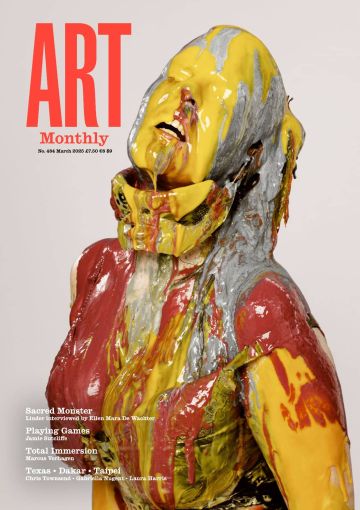

Cara Despain, slow burn (Factory Butte), 2022

It feels a trifle odd to be in a gallery in Houston, looking at the work of an artist who grew up in the same small English village as I did along the foot of the North Downs on the spring line, where gentle chalk hills meet clay vale. Yet Tacita Dean’s playfully critical responses to the disciplinary technologies of the Enlightenment, on show at the Menil Collection, are perhaps as good a starting point as any for thoughts about the sublime, desiccated alkali-landscape of the American West. Dean’s innovative use of obsolete methods to corrode the containing effects of denotative media – photography, film, sound recording – subtly draws attention to the problematic utopianism of the Enlightenment and its aftermaths, and shows how nature escapes the containing boundaries of technology to overwhelm human aspiration. I’m in Texas on a writing fellowship, in the small town of Corsicana, about an hour south of Dallas, on the edge of the pine forests of the eastern part of the state and the western plains. I’m working on an essay about the relationship between poetry, performance and Earth Art in the 1960s and 1970s, thinking in particular about the work of Nancy Holt but also about the part that Earth Art and poetic descriptions of landscape – for example in Ed Dorn’s long poem Gunslinger, 1968–72 – played in revisionist discourses around the primal myths of America’s 19th-century expansion. This was, originally, to be a letter from the art-town of Marfa, made as part of a road trip into the Texas ‘Panhandle’, written in collaboration with the poet Marie Joe López, but Marie is in no shape to travel: she’s in Los Angeles, sheltering her cats and rare books from an ecocide that mirrors the self-immolation of US democracy. Instead, this letter has become a meditation on the foundational American fallacy that nature can be wholly tamed and turned for profit.

It helps that a fellow resident at the Corsicana project is the American environmental artist Cara Despain. Her video work, such as Monument, 2020, uses re-edited, appropriated footage from westerns to focus on a landscape exploited for uranium mining. Despain’s large carbon paintings, including It Doesn’t Look Like Paradise Anymore (Camp Fire, CA 2018), 2019–20, are made using charred debris gathered from the aftermath of wildfires. These paintings still carry the reek of smoke and drop ash the way an early Anselm Keifer used to come accompanied by a discreet line of straw on the gallery floor. With her ‘Slow Burn’ photo series, Despain mounted photos of the classical western landscape, familiar as movie backdrops – Monument Valley, Factory Butte etc – then strung dynamite string through holes in the frame and lit it, wreaking a trail of destruction across the pristine, romantic image. In a month when the northern part of Los Angeles has been devastated by wildfires, Despain’s critique of the USA’s sense of manifest destiny (a destiny seemingly restricted to white people), and the consequences of its ruinous exploitation of the environment, has a terrifying timeliness.

The fallacy of man’s imagined supremacy over nature is given a heroic twist in the mythifying art of the West. It’s symbolised best, maybe, in Frederic Remington’s sculpture The Broncho Buster, 1895. If a wild horse could be tamed by dynamic masculinity and then put to work, so could the landscape. The Broncho Buster has been exhibited in the Oval Office in the White House since Theodore Roosevelt’s first term (1901–05), and I very much doubt that Donald Trump will remove it, since the work embodies much that the MAGA movement aspires to. Remington adapted the conventions of European history painting and monumental sculpture to romanticise the recent foundational past for a deracinated industrial society with no collective memory, and no lived experience of the colonising process. Remington made his work to capture what he saw as the essence of the authentic West for protected wealthy, metropolitan types like Trump living back in New York and Boston. Yet Remington’s art did not come out of any direct experience of the West. The Broncho Buster came out of the travelling vaudeville ‘Wild West shows’ that, in a 25-year period from the 1870s, almost simultaneously mediated and rendered as entertaining spectacle for the urban immigrant population the brutal historical processes of America’s expansion after the mid century.

From the same source, as the new technologies of filmmaking adapted the conventions of the media that film supplanted, came the western movie that not only legitimated the genocide of America’s indigenous peoples to a huge audience, through the principle of the US’s manifest destiny, but also, by staging it in the spectacular mesas and buttes of Utah, rendered that mass murder heroic. First coined in US politics in the 1840s, the notion of a divinely ordained national destiny was used in 1845 to justify the inauguration of Texas as a slave state within the US and thereafter the expansion of the nation to encompass all land between the Atlantic and Pacific shores. As a moral principle – the spread of democratic republicanism – shielding an economic imperative, ‘manifest destiny’ puts the double standards of British imperialism in the shade. It’s embodied in art in two especially appalling paintings: Emanuel Leutze’s mural Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, 1861, unashamedly displayed in the House of Representatives in Washington, DC, and John Gast’s more allegorical American Progress, 1872, a small canvas more widely disseminated in the eastern market as a chromolithograph. Here, indigenous peoples and wildlife flee, to some unspecified elsewhere, a monstrous, triumphant Columbia, who stomps across the prairie, accompanied by the successive technologies that will conquer the landscape: the covered wagon, the stagecoach and the railroad. MAGA’s notion of American ‘greatness’ as ready for reclamation has many foundational myths – first the Reagan era, and earlier the postwar moment of Norman Rockwell’s art and the expansion of the suburbs. Their point of origin, however, is the establishing of a conterminous USA across the western territories after the Civil War, achieved by the taming of a sublime landscape with technologies of repetition and displacement, whether in steam engines, repeating rifles or the movies.

Fort Worth describes itself as ‘the gateway to the West’ even though these days it’s the more-or-less inseparable western part of a conurbation that includes Dallas and spreads across north Texas. Like Marfa, but on a city-scale, it promotes itself to cultural elites on a ‘classic Western vibe, right down to the rodeo’ (as the musician Leon Bridges recently put it for cowboy-boot consumers in the Financial Times). That’s an aesthetic that successfully elides the true historical conditions of the American West. Dallas-Fort Worth is, in fact, a thoroughly contemporary American city. It’s a metropolis without an edge, as the Corsicana-based writer David Searcy explains it, ‘malls all the way to Oklahoma’. And he’s right: when you drive north on Interstate 35, it’s over 50 miles before you see scrubland; however, west out of Fort Worth on I-20 towards Abilene and, eventually, Marfa, you are soon reminded of the essential flatness of the prairie and, if you care to think about it, the two-dimensionality of its accompanying heroes and villains. The American urban has a limit, but its limited imagination doesn’t. It’s that cartoon simplicity of historical outline that allows the bubble of contemporary wealth-culture to indulge itself in a ‘classic Western vibe’ without facing either the truth or consequences of that vibe’s evolution.

The flatness, and the concern with boundary, also brings to mind, however, the way in which Land Art, at least in the work of Robert Smithson, engaged with contemporary technologies at the edge of the western landscape in the 1960s. In Proposal for Earthworks and Landmarks to be Built on the Fringes of the Fort Worth-Dallas Regional Air Terminal Site, 1966–67, Smithson put forward a suggestion for four works that would ‘draw attention to the fringes of the entire project by using apparently unusable land in four different ways’. Robert Morris was to contribute a trapezoidal earth mound, Carl Andre was to create a crater through an explosion; Sol LeWitt was to encase a 6-inch wooden cube in an 18-inch cement cube and bury it in an unannounced spot within the site; Smithson was to lay a series of seven asphalt squares of increasing size. Smithson had been working from July 1966 as an ‘artist consultant’ for the architects Tibbetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton on a tender for the Dallas-Fort Worth airport contract. Having begun with suggestions for the design of the terminals themselves, Smithson became increasingly concerned with the flat spaces surrounding them. In drawings made on maps given to him by the company, Smithson suggested ‘wandering earth mounds and gravel paths’ between the runways and ‘a web of white gravel … paths surrounding water storage tanks’. Neither the firm’s proposal, nor Smithson’s, would be successful, but Smithson’s desire to somehow mark the boundary of the sprawling air terminal is telling. At the time of its construction, Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) was to become the largest airport in the world. It still strikes me, each time I fly in or out, as the world’s most vacuous airport. After landing you spend longer taxiing than anywhere else, or so it seems; the walk from gate to baggage belt feels longer than anywhere else. Like the conurbation that it serves, DFW is as apparently limitless and as empty of content and morality.

Yet Smithson’s proposed marking is expressed in the terms of flatness that characterise not only any airport but also the Texas prairie. None of the four artworks was to be more than 3ft high (Morris’s mound). The three visible artworks would be best seen from the air, not the ground. From a car, or on a horse, they would be almost indistinguishable from the land on which the airport was built. Despite a scale commensurate with the USA’s grandiose ambitions since the 19th century, Smithson understood that DFW was tiny in the framework of nature: in a letter to the critic Rolf-Dieter Herrmann in 1970, he described it as a ‘speck in the Texas prairie’. Smithson’s wider encounter with the American West – a landscape that ‘daily exceeds my capacity to describe it’, as the Utah-based Despain puts it – allowed him a different perspective upon the limitless expansion of capital that underpins ‘manifest destiny’ in its historic and contemporary iterations. Just before he was slaughtered by US Cavalry at the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, Chief White Antelope of the Cheyenne allegedly had a dictum for his murderers: ‘Nothing lives long except the earth and the mountains.’ As Los Angeles rebuilds, perhaps we should reflect that it might be neither morality nor culture that ultimately checks the course of the American empire, but the consequences of its abuse of nature.

Chris Townsend is a freelance writer and curator, and a senior research fellow of the Henry Moore Institute.

First published in Art Monthly 484: March 2025.