Feature

America Rising

So much expected so little delivered – Michael Corris on post 9/11 art from the USA

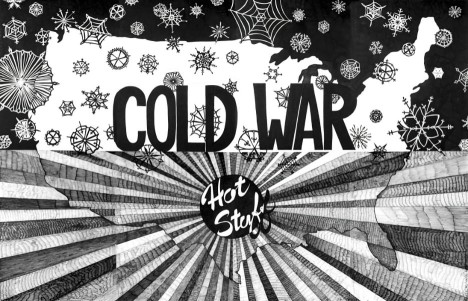

Aleksandra Mir, Cold War, 2005

‘USA Today: New American Art from the Saatchi Gallery’, at the Royal Academy of Arts, and ‘Uncertain States of America’, at the Serpentine Gallery, in London, are both exhibitions about practices and people. The practices are those of contemporary art and the people are a selection of artists living and working in the United States, and both advance the commonplace that contemporary art is overdetermined by contemporary life, although some would argue that the curators and collectors responsible for these efforts reside in different worlds. At this point in the history of art and culture since September 11, 2001, curators and collectors with global reach have more in common than they would care to admit. ‘USA Today’ and ‘Uncertain States of America’ do not stand in opposition but as two sides of the same coin: ‘Uncertain States of America’ is the cool cousin of the relatively conformist ‘USA Today’. No spiralling up or drilling down from one to the other will reveal much about anything except the nature of the singular prison that both exhibitions inhabit. If what is called for is a spatial metaphor to position them, then let us say that these twin accumulations are nothing so much as the glistening surface of a Möbius strip.

These exhibitions of art from the USA appear in London at a time when America’s global relationships have never been so acutely scrutinised and public confidence in the political processes of the state never so low. At the same time, there has never been more faith in the practice of contemporary art to clear a path to some kind of usable moral or existential truth. The American artist asks us to consider the difference between the state and its people. The American artist asks us to consider the diversity of wholesome human aspiration against the monolithic nightmare of the American Dream. The American artist asks us to consider the pain of the average American and to map that onto the pain of the world at the hands of Americans. The American artist invites us to explore their small cultural victories against the backdrop of American military defeat.

When democratic politics fail, when domestic resistance is ignored, and when principled objections are cynically dismissed, art stands as the last refuge against the complete collapse of the values of freedom, self-realisation and community. This is the lesson that ‘USA Today’ and ‘Uncertain States of America’ put before the public: when all other social practices come to grief, art will speak the truth. Art will model a better world. Art will provide the new ways of thinking, of living. The assertion is straightforward: the artist’s toolkit is a credible resource for coping with the world. All contemporary art – not simply American art – comes to us first as a kind of public therapy. What cure, then, for Frederic Jameson’s assertion that ‘the underside of culture is blood, torture, death and horror’?

It is understandable that so much is projected onto art when all else seems uncertain, when all roads appear to be blocked and when all hell breaks loose. You can’t condemn American artists for wanting to use art and its institutions as vehicles to criticise the state and to provoke social and political debate. But this is not the kind of art being offered to us by ‘USA Today’ and ‘Uncertain States of America’. Faced with these two exhibitions, only the dullest commentator would forgo the suspension of belief necessary for the complete enjoyment of contemporary art. But how much faith can one place in work that is little more than an update of Thomas Couture’s The Romans of the Decadence? In the words of one artist in ‘Uncertain States of America’, ‘everything is in a constant state of reinvention’. Everything, it seems, but the culture of art and the self-regard that is held uppermost within it.

There is a unifying logic underpinning both projects and that is how cognisant the curators are of the architecture of the gallery and how it really manages to take hold of our imagination and shape the event. The curator’s hand is revealed in both exhibitions in the most obvious way. At one extreme, there is the architectural scale of the Royal Academy of Arts galleries at Burlington Gardens. The work of ‘USA Today’ did not match the promise of the theme, despite the spaciousness of the setting, the scale of much of the work and the glimpses of expensive production values. Given the chance to breathe, as they say in the trade, much of the work simply expired. At the other extreme, the claustrophobic renovation of the Serpentine Gallery for ‘Uncertain States of America’ aimed to prove, rather too self-consciously, that ‘big-small’ is also a property of contemporary art. To gain an understanding of what has transpired there, look at the installation views of ‘Uncertain States of America’ as it was installed at the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo. There is nothing ‘uncertain’ about the work that was exhibited in that venue, which is modern, spacious and entirely characterless. These architectural qualities – refreshingly unforgiving – help one to fix the true measure of the work, to understand how it offers absolution to those who feel guilty about their cultural and political homelessness. It turns out that the context for much of this art is not, as I had first thought, the warren of cramped, dingy studios typical of our finest art schools. With few exceptions, this work has no context other than that dictated by the site.

Big, bold work full of colour but historically morbid, or a bijou sensibility of accumulated stuff and diffident materiality: that’s more or less the choice on offer. Neither strategy seems to work because it is impossible to identify the audience for this art, impossible to argue for the existence of this work without presupposing the museum. I am certain that the reticence of ‘Uncertain States of America’ is the big point of the exhibition. The poverty of some of the work is supposed to throw the rapaciousness of American capitalism into relief. The overall mess of the installation takes care of those artists whose work may march to the beat of a different drummer. Above all, claustrophobia and edginess – this last, a cliché never far from the hip curator’s lips – burdens all this art beyond belief. Charles Saatchi’s muscular collecting, on the other hand, is in this instance supposed to signify a sense of confidence in the voice of young American art. His confidence in this cohort, in my view, is largely misplaced. We find a significant number of paintings in this exhibition: many are large-scale, panoramic and environmental. Most of these, however, strain to meet the challenge of the cinematic visual experience while forgetting what might be of interest about painting other than its ability to provide us with yet another texture of image. The most substantial sculptural work in ‘USA Today’ – that of Banks Violette – toys with the idea of installation but seems hopelessly deprived of vitality because of its overwhelming frontality. There is hardly any work in ‘USA Today’ that is dark or disturbing or uncertain of itself as anything other than first-quality pictorial art, even though there are works that are ‘abstract’ or make a meal of crude hand-made quality that is currently code for (authentic) dementia.

It is difficult to know which of these two approaches to curating/collecting – the nomadic or the academic – inflict the most damage on the art and the spectator. The nomadic curator seeks out works that validate homelessness and change, and conjure up loose networks of association and circulation. We are confronted with another version of homeopathic criticism: the belief that more of the same, delivered suitably diluted, will make us right again. What we find is a bazaar of visibility, abreaction and opacity. Sometimes nothing new or positive emerges from trauma, just the low hum of making something from scratch for one’s self. I don’t wish to foreclose the possibility that the acting out of trauma as a pretext for art has no validity; I just find the knowing manipulation of breakdown and dislocation condescending and far too accommodating. Yet, if the nomadic curator invites us to move in and out of a personal dream space, the academic curator surely allows no such latitude. ‘USA Today’ revels in obviousness and makes no pretence about weaving magic. It is, by and large, a stifling travesty of the poetic in art. It is much like talking with a dealer at an art fair. By the time I left the exhibition, I felt bullied and dispirited. ‘Uncertain States of America’, by comparison, at least suggested a nervous cough in an otherwise pacified arena.

Despite the gleam of permissiveness, both exhibitions celebrate the illusion that important works of contemporary art are confined to two categories: things and images that move and things and images that do not. There is not a single example of a work in either exhibition that seriously challenges the view that art is at its best when it is more or less a species of medium-sized dry goods. The ‘rhizomatic’ installation of ‘Uncertain States of America’ never gels into a Gesamtkunstwerke, although I’ll wager that the term Zeitgeist was dropped once or twice during the pitch.

If an emblem were required to summarise the effect generated by these two efforts, I would nominate Violette’s SunnO))) / (Repeater) Decay / Coma Mirror, 2006. Take a close look at the guitars and you will notice that they have no strings.

‘USA Today. New American Art from the Saatchi Gallery’ was at Royal Academy of Arts, London October 6 to November 4 2006. ‘Uncertain States of America’ was at Serpentine Gallery, London September 9 to October 15, 2006.

Michael Corris is head of department of art and photography, Newport School of Art, Media and Design, University of Wales, Newport.

First published in Art Monthly 301: November 2006.