Profile

Ali Cherri

Maria Walsh on the Lebanese artist‘s use of dreamlike visions to negotiate conflict

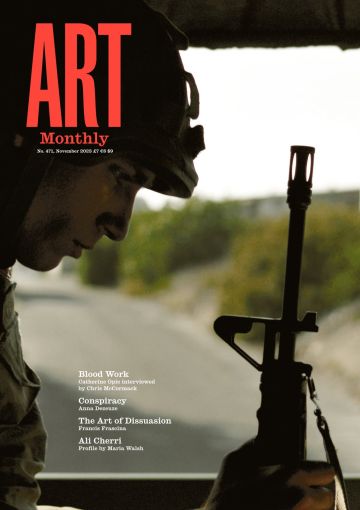

Ali Cherri, The Watchman, 2023

The Lebanese-born Paris-based artist creates a liminal space between life and death, the real and the imagined, primarily using film and video but also large-scale sculptures and delicate watercolours.

Wandering in the National Gallery I came upon five glass cabinets containing sculptural assemblages of objects that hovered between the simulacral and the real, the ancient and the modern. Their interrelations were labile: was the taxidermy goldfinch held in the grip of a large white porcelain hand being caressed or crushed (The Madonna of the Cat (‘La Madonna del Gatto’) after Baroccio, 2022); and who was looking at whom in the configuration of a classical head turned downwards on a mirror, its reflection showing one painted eye staring up at me as I looked at the unseeing scarified ancient Venus figurine lying adjacent on its side (The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’) after Vélazquez, 2022)? The outcome of Ali Cherri’s residency at the Gallery in 2021, the five cabinets in the exhibition ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’, 2022, were three-dimensional translations of images of the ‘wounds’ suffered by paintings in the collection that had been attacked by visitors, a part of their history that is rarely made visible. Cherri’s allegorical assemblages made these histories speak.

In debates on the repatriation of museum artefacts, an object’s silence is often interpreted as an appeal for return to its original homeland or a mandate to remain under Euro-American custodianship. Cherri’s film Somniculus, 2017, while haunted by Statues Also Die, 1953, directed by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet, performs a different kind of intervention than the latter’s indictment of the museumification of the spoils of colonial looting. Opening with the title: ‘If dreamless sleep is a form of death / Then light sleep is a form of resurrection’, Somniculus, shot at night in various museums in Paris, ponders how these migrant objects inhabit the refuge of darkness away from seeing eyes. Cherri sleeps (lightly) in a gallery watched over by Egyptian mummies in glass cabinets or he wanders through the buildings, torch in hand, like a museum guard whose vigilance is not to secure the objects but to probe their mystery. For Cherri, ‘there is no point of origin, or a higher authentic past to which these objects need be returned’; rather, his engagement attempts to tap the visionary potential that survives beyond the histories accrued by the objects in their various states of dislocation. As in the earlier film Petrified, 2016, in which various antiquities are forensically laid out on a lightbox eradicating their shadows, the object’s muteness resists classification, their ritual functions as guardians of life or talismans of death never obliterating their material origins in sand or mud.

The otherworldliness of geological materiality features across the trilogy The Disquiet, 2013, The Digger, 2015, and The Dam, 2022, the first two being experimental documentaries, the latter, a feature, although all three are imbued with a disquieting poetry that touches the violence inscribed in the landscape. The Disquiet tracks Lebanon’s three major fault lines, and also incorporates archival documents of the eruptions that have occurred since 551AD, especially the 1956 Chim earthquake. An opening title states: ‘In Lebanon, the earth trembles between 45 to 60 times each day.’ Only the artist, his body like a seismograph, feels these tremors, his presence inferred by the hand-held camera that tracks along a forest path to the sound of breathing; Cherri only enters the frame in the film’s final sequence, the camera resting on an image of petrified crows spread-eagled on tree tops. An earlier close-up of a red-hued river intimates a bloodbath, while computer-generated fault lines are suggestive of open veins that circulate beneath geopolitical borders. Cherri is now based in Paris but was born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1976, and lived in the country throughout the Civil War between 1975 and 1990. However, rather than representing catastrophe or post-conflict trauma, Cherri explores liminal states of consciousness to allude to damage allegorically.

Shot mainly at the Neolithic necropolis of Jebel Al-Buhais in the emirate of Sharjah, The Digger follows, from afar, Sultan Zeib Khan, a Pakistani man who has been the site’s caretaker for two decades. Framed in long- and mid-shot views, he goes about his daily rituals of cleaning the tombs and keening for the bodily remains that were unearthed and moved to a museum, the excavated graves remaining like gaping wounds in the arid desert and surrounded by inhospitable mountains of rock. Portentous film music intermittently adds a cinematic resonance to the observational documentary, while the film’s soundscape, in which the buzzing of flies predominates, aurally evokes a sense of decomposition.

The Dam focuses on a brickmaker, Maher (Maher El Khair), who plays himself in this speculative fiction. The film premiered at Cannes in 2022 and was in production at the same time as Cherri’s contribution to the 2022 Venice Biennale, the three-channel video installation Of Men and Gods and Mud, for which he won the Silver Lion for Promising Young Participant. Both films are shot in Northern Sudan near the site of the Merowe Dam, a controversial hydroelectric project that involved flooding inhabited land, causing mass evacuation and ecological destruction. Both films focus on the area’s brickmakers, and use some of the same footage, but for different ends.

While Cherri considers himself first and foremost a video artist and filmmaker, he also fabricates standalone sculptures, hybrid figures derived from grafting different sculptural forms and fragments of antiquities both fake and ‘authentic’ that he sources on the open market. Sculptures, drawings and paintings also emanate from his film projects. The installation of Of Men and Gods and Mud included three figurative sculptures, Titans, 2022, made of mud, sand and resin and based on Assyrian Lamassu, as well as delicate watercolours of the site. Visually, the three-channel film is a fairly straightforward, choreographed montage of footage of the site and the brickmakers, shots often homing in on their deft handiwork and on their legs wallowing, or trapped, in the mud. Although there is no dialogue, the workers’ harsh living conditions, their exploitation and poverty, is palpable, but this reading is troubled by the voice-over. This consists of two female narrators who recount, one in an American-accented English, the other in Arabic, translations of poetic fragments based on the Gilgamesh epic, involving said demigod and his sidekick Enkidu, a man made from clay, who is eventually destroyed. There are evocative references to ‘the man with the iridescent eyes’ and slippages between the translations. The incongruity of myth and poetry in relation to the documentary footage of the young Sudanese men unsettles a reading that would situate them purely as socio-economic casualties. Instead, their dignity and skill predominates.

Finding beauty in lives being lived at the margins of socio-political events, while attending to the exploitative conditions of labour, is further explored in The Dam. Maher is a brickmaker, but he has a dream life beyond labour and outside the media broadcasts that cover the 2019 military coup in the country. In his own time, Maher is building an enormous golem-like figure from mud, which appears at different points in the film as an animated mass that speaks to the brickmaker, first in a dream, and later in a hallucinatory vision. In this shift from documentary to speculative fiction, The Dam develops the magical moment at the end of Of Men and Gods and Mud in which a man holding a lantern descends in the far distance from the top of a rocky crevice, the footage superimposed on the night sky above the horizon.

These speculative elements are accentuated in Cherri’s short feature The Watchman, 2023, commissioned and produced by Fondazione In Between Art Film, which premiered at GAMeC (Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo) in the large-scale solo exhibition ‘Dreamless Night’ curated by the Fondazione. Set in Louroujina (Akincilar), a Turkish-Cypriot village on the militarised dividing line set up in 1974 between the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and the recognised Republic of Cyprus under Greek-Cypriot rule, the film focuses on a Turkish soldier, Sergeant Bulut (Halil Ersev Gökçek, a non-actor who had just completed military service). Alone, he guards the border at night from a makeshift military watchtower. Slow-paced sequences playing with the cinematic language of shot/reverse shot, frames-within-frames and off- and onscreen action, create a moody atmosphere. The soldier’s semi-comatose state of stupor is broken by hallucinations of lights signalling from the ruins beyond the border, the ‘enemy’ eventually materialising on the far horizon in the guise of a ghostly platoon of armed soldiers. Eyes tightly shut, their pallor grey, the phantom Greek army marches forwards like the return of the repressed until their leader, inhumanly yet unthreateningly, stands towering above the Turkish watchman.

A dialogue ensues between Sergeant Bulut and the ghostly leader, whose ‘voice’ sounds like crumbling rock rather than speech. ‘What would happen to me if I went with you?’, the watchman asks. It is as if he has crossed into a liminal space in which the fear of the other that maintains division is momentarily dissolved. This enigmatic allegory is magnified in the sculptures that are displayed in GAMeC’s upper galleries, each in a room of their own. A deconstructed symbol of power, The Dismembered Bird, 2023, greets the viewer, its eagle head an ‘antique’ artefact whose wings and torso, made from clay and sand, rest separately on iron girders, while its legs stand incongruously in a corner. In The Seven Soldiers, 2023, large-scale hollow heads of soldiers with eyes closed hover suspended on iron supports slightly above eye-level. Cast in fibreglass and resin, their sickly greenish pigmentation adds to their haunting critique of supposedly heroic military endeavour. Wake up Soldiers, Open Your Eyes, 2023, consists of two statuesque soldiers cast in mud and plaster. While their thick militarily booted feet are solidly planted on the ground, their upper torsos, including weapons, gradually flatten, their faces partially eaten away, as if they are collapsing in on themselves.

This sense of decay is further encapsulated in the final display of resin-cast sculptures of the diseased prickle pear plant which, in the film, runs along the dividing line between North and South; here the sculptures are grouped in semi-circular formation, the border disassembled. ‘Dreamless Night’ also includes a series of beautifully executed watercolours of the cactus in flower as if reclaiming beauty from decay, while a large-scale watercolour of a taxidermy robin picks up on the moment in the film when the bird smashes into the watchtower’s window, its death allegorically standing in for bodies fallen in war.

In its under-the-radar contemplation of catastrophe, ‘Dreamless Night’, like much of Cherri’s work, accesses a liminal space between life and death, a space that art can offer to complement the political resolutions necessary to facilitate cross-border dialogues between the wounded on all sides of geolocational divides.

Ali Cherri’s ‘Dreamless Night’ is at GAMeC Bergamo to 14 January, 2024, before travelling to Frac Bretagne, Rennes in February 2024.

Maria Walsh is reader in artists’ moving image at Chelsea College of Arts and author of Therapeutic Aesthetics: Performative Encounters in Moving Image Artworks, 2022.

First published in Art Monthly 471: November 2023.