Feature

Against Immersion

Adam Heardman looks beyond the spectacle of high-tech immersive art experiences

an escaped helium party balloon trapped against the ceiling of The Summer Palace, Agustin Vidal Saavedra’s immersive video at Outernet Arts, London

Anyone with even a passing interest in the world of visual art will have noticed a recent drive towards ‘immersion’. Current exhibitions of new work in London – including David Hockney’s installation at Lightroom, Mark Leckey’s VR piece at Swedenborg House, and the built-environments of Mike Nelson and R.I.P Germain at the Hayward and the ICA (Reviews AM466) – share the goal of totally immersing viewers in their constructed worlds. At the same time, there’s the latest round of Instagram-oriented ‘immersive experiences’ (the current iterations based on the work of Salvador Dalí and Vincent Van Gogh) run by an events company, Fever, which ask that eternal question: ‘Have you ever dreamed of stepping inside a painting?’

Whether or not you feel such shows are gimmicky or cutting edge, it is undeniable that they are becoming an increasingly prevalent and powerful aspect of the cultural sphere. The two current Fever exhibitions follow on from others based on the work of Gustav Klimt and Frida Kahlo. Lightroom, which launched with the current Hockney show, is a permanent space specifically designed for such installations (it is funded by Leonard Blavatnik and a former CEO of Goldman Sachs, Mike Sherwood, more on which later). How does this affect our relationship with art? Is it a harmless fad or a sign of some more sinister co-option of the cultural space? If the latter, how to resist it?

Promising ‘mind-blowing’ and ‘multi-sensory’ encounters with artworks, the Van Gogh Immersive Experience and the Dalí Cybernetics Experience, both held in vast warehouse spaces in east London’s Shoreditch, turn out to be almost comically phoned-in, cheaply produced, shoddy attractions. The Van Gogh show begins with a large room full of the painter’s most famous works screen-printed onto small canvases. To say they look as though they have come straight from the ‘art’ section of Ikea would do a disservice to the furniture store, as would comparing the faux households of the Ikea showroom with the flimsy diorama of Van Gogh’s Bedroom at Arles, which greets you round the next corner. Both shows offer a VR experience, for which a headset must be worn. At the Van Gogh, you have to pay an extra £6 for the privilege, unless you have purchased a VIP pass for £44 (a standard adult ticket is £27.90).

The VR experience comprises a slow walkthrough of wheatfields and provincial landscapes rendered in 3D graphics that would make a PlayStation 1 games developer blush. Equally clunky is the trip through a Salvador Dalí-inspired, ant-ridden desert on a boat that transforms into a dripping clock. These might offer a fun enough diversion, but it is hard not to feel as though it is all a bit of a scam. Perhaps even more so in the huge projection rooms, where blaring orchestral music, or a nauseatingly earnest voice-over reading the most inspirational-sounding snippets from Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, Theo, try to conjure the sort of emotional response that surely could never be instilled by the montage videos of details from the artists’ works – all Ken Burns pans and weird animation – that fill the walls and the floor.

There is clearly little or no input from curators, researchers, art historians or experts of any kind, and the experiences are gallingly hollow. It’s not just the peddling of a lacklustre product for profit that’s worrying here (that is a concern for the art world, and the world at large, in ways that are beyond the scope of this piece). More specifically, what bears some direct attention is the particular ways in which such exhibits treat both the art and the viewer, and how this approach represents a threat to the role of the creative arts in society.

A first and obvious point is that, throughout the Dalí and Van Gogh presentations, there is no first-hand experience of any physical work by either artist. Granted, securing the acquisition or loan of a real work is not necessarily what these things are ‘about’, but the absence of any actual art itself is already an uncanny start. Any argument that these shows make the artworks more accessible to those who cannot visit, say, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam are rendered void by the prohibitively expensive entrance fees and the seemingly total lack of lifts, ramps or other access requirements inside the warehouse spaces that house the exhibits.

Not only that, there is no faithful or high-resolution reproduction of any whole work, the experience being instead given over entirely to animations of details. Not once are we given a still-frame of The Persistence of Memory, 1931, or Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, to allow for the opportunity to appreciate form, composition, colour, tone, treatment of light and space, or any of the artist’s intentions or material gestures. For an experience that purports to give you the sensation of ‘stepping inside a painting’, these shows could not more fully erase the painting from the scene.

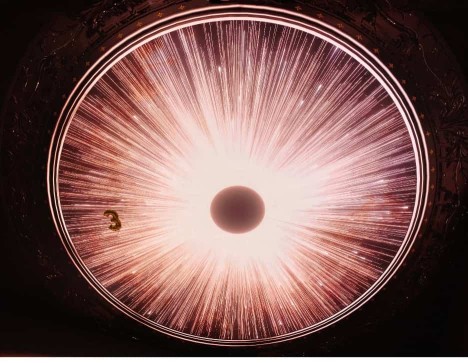

Further, and perhaps more troublingly, you, the viewer, are also erased. Everyone’s first instinct when donning a VR headset and entering the virtual world is to look down at their own body, only to find that it has disappeared. Similarly, in the projection rooms, the full bleed of the visuals means that you are simply treated as another surface onto which the video is projected. Not only do you not feel like you are existing inside a painting, you don’t feel as if you exist anywhere at all.

This effect may seem cosmetic at first, but it represents a total short-circuiting of the intended relationship between artwork and viewer. Far from being an active, experiencing subject in dialogue with an artwork that is meaningfully addressed to you, in the projection room or the VR space you are in no real sense ‘addressed’ by the ‘work’. You become a passive receptacle for a dazzlingly hollow spectacle. Not only are you being sold an inferior product at a premium price, but you are also treated like (and essentially transformed into) a smoothed and uncritical entity, an observer of the most pacified and least independently curious kind. It’s not hard to imagine the social and political import.

In their book Investigative Aesthetics (Books AM449), Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman address how the ‘aesthetic’ sensibilities of individuals and collectives operate sociopolitically. In their definition, ‘aesthetic’ is the opposite of ‘anaesthetic’, and simply refers to a heightening of the senses to meaning and information. Of course, the common usage of ‘aesthetic’ to suggest a concern with ‘beauty’ is retained – beauty is a particularly potent heightener of the senses – but broadened to include all kinds of stimulated informational experiences, from historical events to trauma.

Fuller and Weizman dig forensically into the implications of aesthetics, as well as hyper-aesthetics (a super-heightened state of aesthetic awareness that includes systems of sense-making) and hyperaesthesia, where a glutted stream of information overwhelms the senses and confounds sense-making capacities. Aesthetics, hyper-aesthetics and hyperaesthesia, Fuller and Weizman argue, can be mobilised both by hegemonic power structures and by those who resist them.

There is an argument to be made that the immersive exhibitions are an example of hyperaesthesia. They self-proclaim as delivering ‘mind-blowing’, ‘multisensory’ experiences, a deliberate overwhelming of the senses. They also ooze a kind of dumbstruck awe at the idea of ‘art’ and ‘great artists’, a stiflingly monolithic version of cultural experience. In Fuller and Weizman’s diagnosis, ‘The moment when registration becomes erasure that arrives through oversensitivity is one of the basic forms of hyperaesthesia’. We have already seen the kinds of erasure that the multisensory exhibits enact. Hyperaesthesia, ‘a central tool of state terror’ according to Fuller and Weizman, might thus be mobilised within the sphere of art and entertainment to suppress a populace’s creative and sense-making capabilities in the very spaces where they are usually allowed free reign.

There is, however, another subtler and perhaps more pertinent way in which Fuller and Weizman’s thinking can be brought to bear on the world of immersive art. To further elucidate this, it is worth bringing in Hockney’s current exhibition, the inaugural show at London’s Lightroom. Because the artist had direct involvement in the presentation, there is a little more going on here than in the Fever attractions: the show takes the form of one enormous projection room where videos play on the walls and on the floor. At one point, Hockney describes his experiments with perspective and his disdain for the vanishing-point technique to create a sense of depth that pretty much all European painting used since Leon Battista Alberti theorised it in the mid-15th century. The recreation of a one-point perspective image as seen by a camera obscura is, for Hockney, an erasure of the human subject in preference of a technological viewpoint. In recreating what the camera sees, the viewing subject is removed from the scene. ‘If you do it this way … you’re not quite there, actually,’ Hockney says. Much of his art attempts to unlearn this type of image creation in favour of the continuous planar zones of Chinese landscape painting. ‘You’re seeing yourself move inside the picture,’ Hockney declares about this approach. ‘You’re in it, in a sense.’ Arguably, Hockney believes a form of immersive image can recentre the experiencing subject and overcome the tech-inflected barriers to truth that come with received structures.

It is unclear whether Hockney truly believes that the immersive spectacle of the Lightroom show successfully enacts this vision. It comprehensively does not, just to be clear, and perhaps he is aware of this. A sympathetic reading of the exhibition would see its self-referentiality as a kind of kitsch and cheeky challenge to the medium itself, a critical and creative move which cuts through the hyperaesthesia of the show’s blank light, using its medium against it in a productive tension. If that is what he’s up to, it’s a canny dodge. Still, though, there is very little original art in the show. A quick montage of stencil-like figures acting out Hockney’s favourite operas is the only ‘new’ work, and this section offers only brief respite from what is essentially a retrospective documentary, falling into the same traps as the other immersive exhibitions: swelling music, meaninglessly animated versions of existing works, glib quotation-snippets about the creative process. There’s still that sense that you are existing in an abstracted zone from which both ‘you’ and ‘the work’ have been erased.

Further, the Lightroom venture itself, and Hockney’s collaboration, signal another complex problem with the increasing prevalence of this spectacle/commodity-based approach to culture. As mentioned, Lightroom is funded by a group of investors led by businessman/philanthropist Leonard Blavatnik and Mike Sherwood, the former CEO of Goldman Sachs International. Ukrainian-born Blavatnik is Britain’s richest man, and his serial donations to cultural institutions have drawn intense scrutiny. He is strongly suspected of ties to Russian oligarchic interests – in 2022, the Guardian reported on internal emails sent between colleagues at the National Library of Scotland, after they received a donation from Blavatnik, in which they discussed his relationship with sanctioned Russian businessman Viktor Vekselberg and even of having ties to Vladimir Putin himself, something Blavatnik strongly denies. As well as funding Tate Modern’s extension, the Blavatnik Building, the billionaire also donated a million dollars to Donald Trump’s inauguration committee.

Such figures taking an interest in the cultural sphere is of course straightforward artwashing, but when linked to tech, as in the instance of Lightroom, it also becomes part and parcel of an insidious shift towards the digitalisation of culture, with its implications for corporate control over presentation/distribution and associated data surveillance – QR codes, location services, the offer, from Fever, to ‘become a Fever influencer’ and ‘promote the event on your socials in exchange for tickets’.

Building the exhibitions around monolithic cultural figures like Hockney, Van Gogh, Dalí etc, while overwhelming the critical faculty of visitors, also feeds into a form of behavioural predictability that bolsters oppressive systems of control. As Fuller and Weizman articulate, increased predictability of human behaviour within a populace feeds into systems of state oppression. In one of their many recent works, Forensic Architecture, the collaborative group of researchers, artists, architects and representatives of many other disciplines that was founded by Weizman, analysed the killing of black barber Harith Augustus by Chicago police in 2018. Such use of lethal force by police is often justified by the argument that officers operated on a ‘split second’ impulse, fearing their lives were in danger. Forensic Architecture interrogated the ‘split second’ explanation by mapping the incident in milliseconds, seconds, minutes, hours and years. The ‘split second’ was shown to recreate, in an instant, biases and structures of power that operated and were culturally ingrained over decades. What was said to be a ‘reasonable assumption of risk’, which supposedly justified the officers’ use of lethal force, was in fact greatly influenced by racial and class-based prejudices, and followed the logic of systemic social hegemonies that had played out over long periods of time. In this sense, it is clear that the structurally enforced or prejudicially imagined habits of the collective can be used to perpetrate and justify systems of oppression and violence.

The artistic sphere is an affective, operative space in which it is our duty to behave unpredictably, to come together to overthrow the expected or hegemonic systems of feeling, desire, activity and thought that are being weaponised against us. Seen in the light of these discussions, the current proliferation of immersive exhibitions seem specifically designed to produce and perpetuate an algorithmically calculable form of cultural activity by short-circuiting the ‘aesthetic’ experience, to reinforce the monoculture of ‘great artists’ and the distraction of ‘newfangled tech’ as a tool of control. It is not hard to see how this pacifies art as a space for resistance, and could also be used in future to justify removal of funds from education, fringe arts organisations, or even to ostracise certain social groups. It is notable that the UK’s first permanent immersive digital art gallery, the Reel Store, which launched as a legacy project of Coventry’s UK City of Culture programme a year ago, has already entered administration while owing the City Council £1m in unpaid loans (Artnotes AM465). Outernet Arts, meanwhile, which sits in the shadow of London’s Centre Point and boasts ‘the biggest digital exhibition space in Europe’ with ‘the world’s largest wrap-around screens’, launched last year as an integral component of the £1bn redevelopment of a prime site that was once home to music venues and artists’ studios (Artnotes AM461); Outernet’s vast screens run all the time, but its art programme is limited to Sunday afternoons. In a UK where both major political parties seem equally keen to establish a police state and stifle activism, any burgeoning system of control must be eyed with suspicion, perhaps especially one encroaching upon the arts, where exploration, expression, unpredictability and interrogation of received structures should be paramount.

Forensic Architecture deliberately brings an aesthetic approach to its research, displaying in galleries and using 3D imaging and other (arguably ‘immersive’) elements to conceive of its research projects as works of art. The recent ‘built environment’ exhibition by R.I.P Germain, shown at the ICA in London, uses an immersive mode to interrogate the ways in which access to space is socialised and politicised. Nelson’s exhibition at the Hayward Gallery collects some of the artist’s labyrinthine, multi-roomed worlds which help to make palpable a post-apocalyptic imaginary (though, admittedly, in a way that is often more diversionary than affective). These are just some examples in which immersion can be activated as a creative, exploratory medium. Fully immersive art is here to stay, and we must contend with it productively lest it be used, paradoxically, as both a form of surveillance and a system of erasure through which, to quote Hockney again, ‘you’re not quite there, actually’.

Adam Heardman is a writer and poet based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 467: June 2023.